By Bobbie Chew Bigby (Cherokee)

In most people’s minds, the words “southern California” usually conjure a number of stereotypical images—palm trees, sunshine, Hollywood, Beverly Hills, and Baywatch beachside scenes are just a few. Yet journeying deeper into southern California’s desert heart, lying south of the Joshua trees and not too far north of the Mexican border, sits the Salton Sea and the surrounding Imperial Valley communities. The Salton Sea is widely known as California’s largest lake. Still, it has also more recently developed a reputation as a body of water that is in severe trouble as it has evaporated, shrunk, and become inhospitable to much aquatic life that cannot tolerate its extreme salinity. The Sea’s retracting shorelines have also led to increasing threats of toxic dust from the farming industry contaminating the area and harming human health. As agricultural runoff of pesticides and fertilizers from the surrounding Imperial Valley has drained into the Salton Sea over decades, the chemicals that once sat at the bottom of this body of water are now being blown around as toxic dust as the lakebed dries.

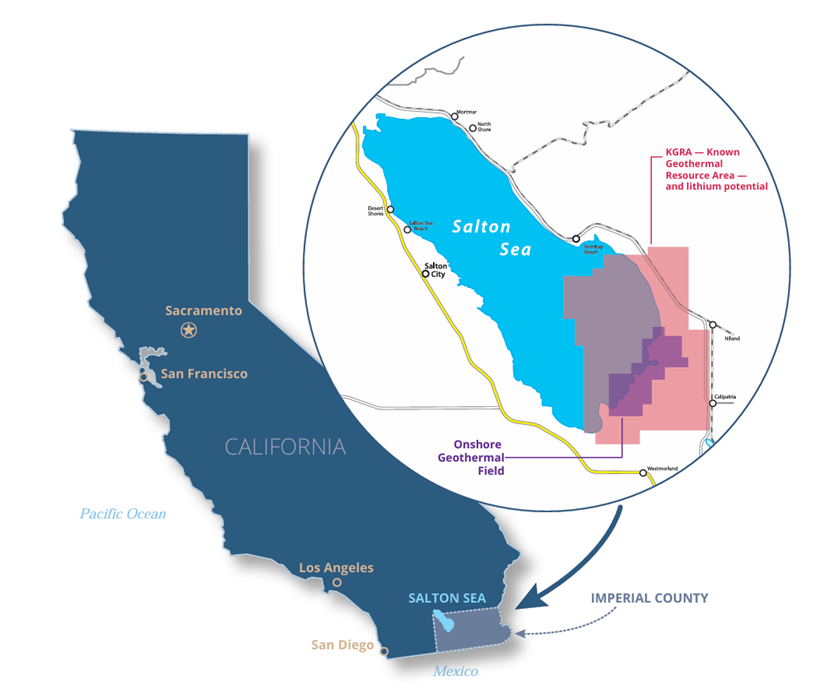

A map of California, with a magnified view of the Salton Sea in Imperial County, as well as the Known Geothermal Resource Area. Image courtesy of Earthworks.

Birds at the edge of the Salton Sea. Photo by Mariana Kiimi Ortez Flores.

However, the legacies of the Salton Sea and the Imperial Valley are much more complex than is reflected in this story of the Sea’s evaporation alone. For well over a century now, many groups of people have come to envision and build what they have wanted the Salton Sea and Imperial Valley to be, whether that is a salt works industry, a tourism hub, an agricultural and cattle heartland, or a site of geothermal and green energy sources. What connects these diverse visions imposed upon the Valley and the Sea has been a push for economic development, industry, extraction, and production in a desert environment of unique beauty and ecological extremes. In California, the Imperial Valley is one of the more economically challenged areas in the state, with high unemployment and poverty rates, even though the Valley still serves as an agricultural powerhouse (Electric Futures | Episode 1: The White Gold Rush). Drawing on water from the Colorado River, the Imperial Valley’s agricultural industry supplies the US with much of its winter vegetables and beef. Yet today, these conversations and the push for finding the right industry to offer employment to Imperial Valley residents continue beyond agriculture alone, with a strong focus on extracting a mineral key to today’s energy transition: lithium.

Lithium produced for commercial uses takes the form of lithium carbonate. It is recognizable as a light, powdery white substance increasingly referred to as a new “gold,” given the high global demand. Lithium is an essential element for battery functioning and an indispensable component of electrification processes that are part of proposed alternatives to fossil fuel burning. Lithium is needed not only for electric vehicles, but for nearly all battery-operated technology, ranging from tooth brushes to vacuum cleaners, and is also used in smartphones, pacemakers, and everyday technology embedded into mainstream society.

Depending on the specific geological conditions and infrastructure available, lithium has usually been extracted using two primary methods across the globe: hard rock mining or evaporation pools. In places such as southwestern Australia, home of the Noongar Aboriginal Traditional Owner groups, hard rock mining of lithium has been the preferred method of extraction. In these open-pit mines, lithium is mined from rocky ores in the form of spodumene using drill and blast methods before being hauled and sorted (Love of Place Over Lithium: Learning, Connecting, and Valuing Noongar Country).

A haul truck winds its way around the rim of the open-pit lithium mine owned by Talison Lithium in Greenbushes, Western Australia. Photo by Bobbie Chew Bigby.

An interpretive sign next to the mine pit lookout for visitors and tourists to learn about the mining process involved with extracting hard rock lithium. Photo by Bobbie Chew Bigby.

A second sign at the mine pit lookout that describes the processing steps required for the hard rock lithium. Photo by Bobbie Chew Bigby.

In South America’s ‘Lithium Triangle,’ an area comprising the high-altitude desert plains where Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile intersect, lithium is extracted not from hard rock sources but from mineral-rich brines underground. Using the evaporation method, these mineral-rich brines are pumped to the surface, where they are emptied into vast pools. The sun then does its work to evaporate the water from the brines over months, leaving behind higher concentrations of solid minerals, including lithium. While the evaporation pools are generally noted to be a less energy-intensive form of extraction compared with hard rock mining, both methods have major environmental impacts, including ecological destruction and intensive water use. This reliance on water, whether in the form of brines pumped from underground or used in other extraction processes, is also important to note, given that lithium is often found in some of the world’s driest and most fragile ecosystems, including the Atacama Desert of South America. As a consequence, intensive use of water in these areas can leave behind a massive footprint impacting not only the water needs of local Indigenous communities, but also the flora, fauna, and wildlife that inhabit these unique habitats.

An aerial view of a lithium evaporation pool at the edge of Bolivia’s iconic Uyuni salt flat. Credit: Wikipedia.

Andean flamingos scavenging for food in northern Chile’s Atacama Desert region, where multiple lithium evaporation ponds are nearby. Local guides in the area remarked that the reason the flamingos are pale white in color, rather than their characteristic pink hue, is due to the levels of malnutrition of the birds, as food has become harder to find in the decreased water sources. Photo by Bobbie Chew Bigby.

The potential for lithium extraction in southern California’s Salton Sea area represents a new and emerging approach for obtaining this mineral that, as yet, has not been tested at scale. As opposed to using hard rock mining or evaporation ponds, lithium producers around the Salton Sea’s southern shoreline look to build upon the existing geothermal technology that has been operating for decades by generating energy from hot steam. With geothermal companies long having harnessed the flashes of hot steam to drive turbines, this steam has also brought with it salt, lithium, silica, manganese, and other minerals forth in the brines coming from underground. As a result, energy professionals have proposed a method of obtaining lithium called Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) that builds upon this existing geothermal infrastructure. Using emerging technologies that would specifically separate, absorb, and extract lithium from the brines, the remaining fluids would be pumped back and returned underground in a cyclical fashion. While this DLE technique is touted for being much less invasive and destructive in comparison with the other current mining processes, there are still many unknowns among the three companies currently pursuing this technology, including whether or not DLE will work at scale.

A geothermal plant operating near the Salton Sea in the Imperial Valley. Photo by Mariana Kiimi Ortez Flores

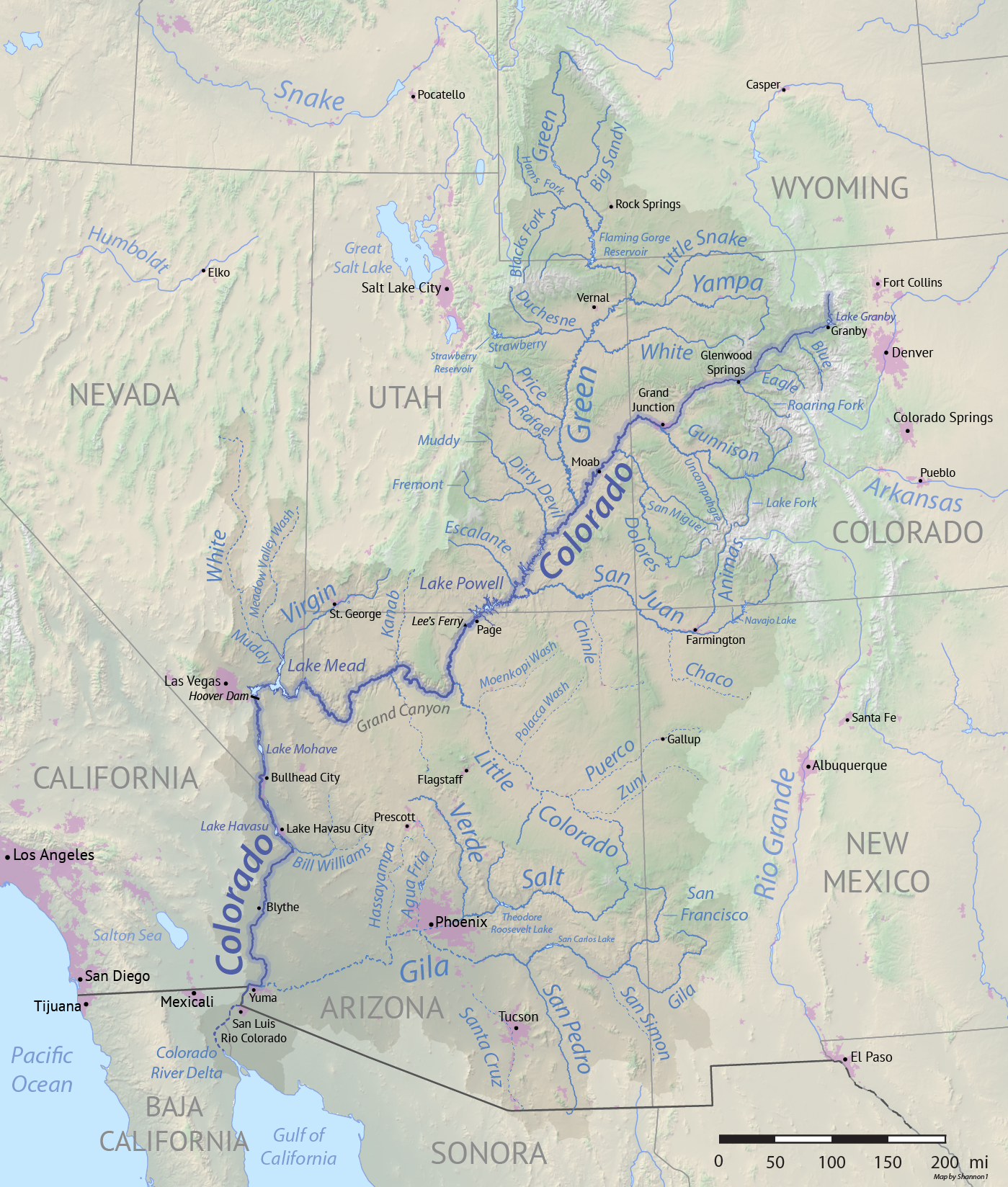

Additionally, according to a report "Environmental Justice In California’s Lithium Valley" done by nonprofit organization and SIRGE Coalition member Earthworks, which looks holistically at environmental justice issues related to Salton Sea lithium ambitions, there are other potential sources of concern. This report identifies five areas for special attention where environmental justice needs to be assured for people and place alike, including impacts on air quality, freshwater consumption, further Salton Sea degradation, management of hazardous waste, and seismic activity. Like in other places that are lithium-rich and prime for lithium extraction, the question of freshwater usage and management becomes paramount. This is particularly notable given the fact that the freshwater required for extraction processes such as cooling and mineral processing will come from the Colorado River, a river system already known for being highly vulnerable and increasingly depleted. The Imperial Valley already uses more Colorado River water than any other area of the Western United States (Electric Futures | Episode 1: The White Gold Rush). According to the Earthworks report, this freshwater consumption from the Colorado River needs to be managed carefully, given that the lithium industry would likely need more river water than is currently allocated to Imperial Valley for the agricultural industry. Furthermore, efforts at managing the Salton Sea’s shrinking by diverting Colorado River water may also run into challenges in reduced allocations of water, potentially allowing the Sea to shrink and increasingly exposing toxic dust sediments.

Yet by zooming out the lens through which we see the Imperial Valley and Salton Sea, and understanding how these lands and waters are but one, interconnected part of the broader Colorado River system, we can gain a deeper appreciation not only of this environment, but also of the Indigenous Peoples who have always been the stewards of this area. Multiple Tribal Nations have been the traditional stewards of these lands and waters, including the Cahuilla, Quechan, Kumeyaay, Kamia, among others. These Peoples have long maintained deep cultural and spiritual connections to the unique geological formations that comprise the area. Rather than seeing these ancient volcanic buttes of obsidian, mudpots, or hot geysers as simply an economic mine for lithium and geothermal energy sources, these landscapes are living, sentient, storied, and deeply interconnected with these Peoples’ cultural lives.

The Indigenous steward groups of what we now call the Imperial Valley have always understood that the Salton Sea was part of the larger Colorado River watershed, deeply connected to this long, grand river that snakes through much of the US southwest as well as Mexico (The Settler Sea). Beginning from the start of the Colorado River from the snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains, it winds through multiple states as well as the Grand Canyon, before its tail reaches southern California. While what is now known as the Imperial Valley today is generally considered to be a desert landscape, the Indigenous communities had long known that the area was prone to floods throughout history. Approximately every 500 years, the valley would see flooding when the Colorado River—understood by local people as a rattlesnake—would twitch its tail by diverting from its normal course and form an inland sea. This inland sea was known as Lake Cahuilla and even today, the Salton Sea that has existed since the flooding of the early 20th century is seen as the latest manifestation of this ancient Lake Cahuilla. While the Indigenous peoples of the area had lived in relation to this ebbing and flowing of the rattlesnake’s movements through water and land, the present-day demands of industry, extraction, toxic agricultural runoff, and water depletion can make it hard even to envision the rattlesnake and how people can live with it.

A map of the broader Colorado River basin. Credit: Wikipedia.

During a visit to the Salton Sea in September 2024, attended by members of Cultural Survival, visitors heard directly from several of the Indigenous traditional stewards in the area about how they understand, respect, and want to protect these vital land and waterscapes in the face of threats from industry. Taken first to the volcanic outcroppings along the shore of the Salton Sea, Elders Carmen Lucas (Kwaayumii Laguna Band of Indians) and Preston J. Arrow-Weed (Quechan and Kamia) introduced the group to the Obsidian Butte area. This area is sacred for many Tribal members as the volcanic activity has always represented how alive Mother Earth is beneath the land, with active fire burning below. According to Carmen Lucas, a black and white serpent is understood traditionally as having created this volcanic landscape, and the pieces of shiny obsidian that dot the area are evidence of that serpent that blew itself up and spread its knowledge across the landscape (Electric Futures | Episode 5: From the Twitch of Colorado River's Tail to Kwaaymii Point). In response to a 2010 report for the California Energy Commission that determined that geothermal and other industrial developments would have substantial impacts to this active volcanic cultural area, Lucas states that, “We must think about the next generations, they’re entitled to know their culture.”

A group of visitors, including Cultural Survival staff, standing at Obisidian Butte next to the Salton Sea. Photo by Mariana Kiimi Ortez Flores.

Elder Carmen Lucas (Kwaaymii Laguna Band of Indians) holding a piece of clay from near the Obsidian Butte area. Photo by Mariana Kiimi Ortez Flores.

This culture is not only manifested in the living fires that are beneath the land’s crust, but also in the fact that these Tribal communities had long maintained deep knowledge of the area’s water sources, growing seasons, and interconnected trade routes across this landscape. Certain Tribal communities were aware of and able to access deeper wells of fresh spring water, while others could access those that were more shallow. Controlled burns had been carefully practiced, allowing mesquite trees to thrive, and agriculture was developed in relationship with generally arid landscape, allowing for short growing seasons. From this heart of the southern California desert valley, Indigenous traditional stewards were able to responsibly harvest salt and other minerals, such as obsidian. This salt and obsidian were then traded with other Tribal Nations on the southern California coast.

Back at the southeastern shore of the Salton Sea in the active volcanic district near Obsidian Butte, the group of visitors from Cultural Survival was also introduced to an area known as the "Old Mud Pots." From a scientific lens, these hot mud bubbles are the result of geothermal brine bubbling up to the earth’s surface, resulting in puddles of mineral-rich muddy liquid bubbling like a pot of boiling stew. But seen through the eyes, hearts, and wisdom of Tribal Elders, these mud pots again represent that Mother Earth is alive, with each bubbling murmur understood as a heartbeat. Carmen Lucas states, “This gift [of the mudpots] is the oldest gift of the world. Mother Earth is alive, and we have the obligation to keep her alive.” These mudpots are understood as a gift and as medicine to the people who have always inhabited this area.

Old mud pots that are dried at the edge of the Salton Sea area. Photo by Mariana Kiimi Ortez Flores.

Many people in the Indigenous communities of the Salton Sea area have engaged in ongoing opposition to new industry and development that does not take into account the importance and fragility of the cultural landscapes embedded in this unique geologic area. In nearby places where there had been a proposed open-pit gold mine in past years, activism on the part of Tribal members and environmentalists had led to this mine proposal ultimately being withdrawn. In the face of ongoing plans for expanded geothermal development and now lithium extraction, there do remain some tools for tribes and advocates of the living environment to continue efforts at protection. This includes having Obsidian Butte being listed on national and state historic registers, as well as all industrial and development initiatives holding to a commitment to engage in Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) with the Indigenous communities whose traditional lands and waters are impacted.

Yet, perhaps most importantly, beyond legal instruments, court cases or government-sanctioned recognitions, what could most help bring balance back into humans’ relationship with the Salton Sea is to open our minds and hearts to the ways of seeing shared by the Tribal elders and knowledge keepers. Looking at the mud pots, geysers, and strong heat and energy coming up from deep within Mother Earth and understanding these elements as life forces deserving of respect, rather than simply a product to be channeled into profit or energy, is a profound starting point. It has been these traditional perspectives and lifeways, after all, that have allowed the Indigenous communities of the Imperial Valley and Salton Sea area to live in relative balance with these powerful natural forces over millennia. And it will likely be these traditional worldviews and lifeways, grounded in respect and stewardship rather than consumption, that will allow the Valley’s land and waterscapes to support life far into the future.

--Bobbie Chew Bigby (Cherokee) is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, where she researches the intersections between Indigenous-led tourism and resurgence. This article is part of a series that elevates the stories and voices of the Indigenous communities and land defenders impacted by mining for transition minerals.

Top photo: Salton Sea by Katherine McKinley.