By Brandi Morin (Cree/Iroquois)

Photos by Julien Defourny

The water that once ran clear enough to drink now flows a sickly brownish-green, carrying the acrid smell of death down what used to be a living river. Where children once played and fish swam freely, garbage now lines the banks and toxic mining waste piles high on either side. The playground sits abandoned and overgrown, a rusted monument to a community that mining has all but erased.

This is what remains of Seque Jahuira, an Indigenous Aymara community in the Municipality of Viacha, Department of La Paz, Bolivia. And Pastor Carvajal, 62, is one of the few who refuse to abandon it.

His cheek constantly bulges with coca leaves—a sacred tradition in Aymara territory—and he carries a large bag of the green leaves as he moves between communities, organizing resistance. Each morning, following Aymara custom, he asks Pachamama for permission to begin the day—a practice that carries profound meaning as he witnesses a landscape so wounded it can barely sustain life.

"That someday they can live like we have lived," he says of his hopes for his grandchildren's future. It's a dream that requires not just legal victory, but the resurrection of a world that mining has nearly destroyed.

A Community Sold Away

The transformation began in the 1980s with what seemed like a routine transaction: a community member sold his land to a non-Indigenous man who established a brick factory. That single sale opened the floodgates. The new owner later subdivided the property and sold parcels to miners who set up operations without proper licensing and began dumping their toxic waste directly into the river.

"We used to have rabbits, I counted 140 of them. After that I couldn't count a single one," Carvajal recalls, his weathered hands gesturing toward the barren landscape of Seque Jahuira. "I used to have 200 cows, they started dying—about a dozen of them starting in 2006. Each year more and more died, produced less milk, stopped growing."

The environmental devastation forced Carvajal to move his remaining cattle to a community further away, where they recovered. The lesson was clear: the land itself had become poison.

Today, 26 different mining enterprises operate around Seque Jahuira, according to Carvajal's count, with 23 mining companies confirmed by environmental authorities to be using chemical processes that contaminate local aquifers. Six claim to be legal, though Carvajal disputes this, noting they never sought permission from the Indigenous community as required by law.

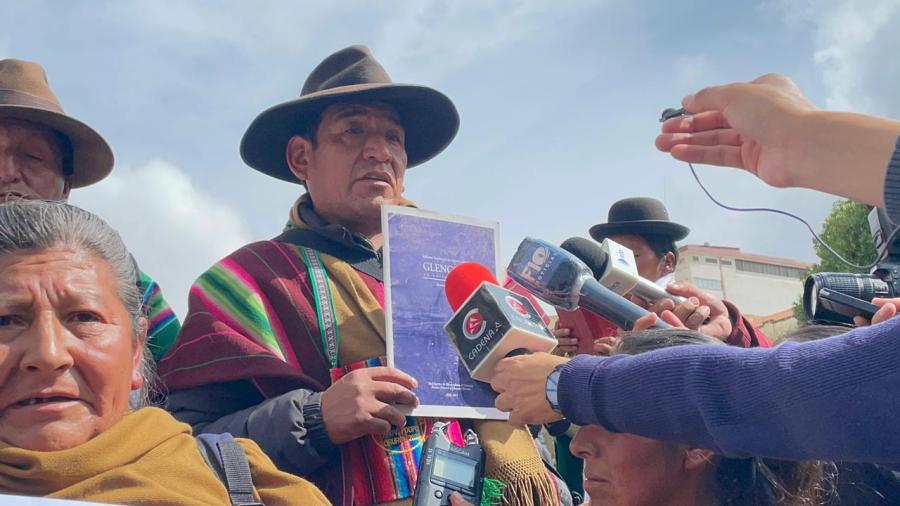

Carvajal serves as an authority in the Jilir Irpirl Justice Council—a position that carries both weight and danger. His role is to advocate, to speak for those who can no longer speak for themselves as their neighbors flee the contamination.

"It's to defend the community, I speak for the community about these problems. They gave me this," Carvajal says, touching the badge that marks his authority. It is a symbol of responsibility in a jurisdiction where four council members serve, though he often faces the mining companies alone.

The isolation weighs heavily. Two of his fellow council members are teachers who frequently cannot attend meetings due to their work obligations. When confrontations arise with mining companies, Carvajal often stands without backup.

The Last Holdouts Against Corporate Capture

Last year, the danger became personal. After organizing other community authorities to confront a Chinese mining company, hundreds of miners appeared and attacked the group. Carvajal had to flee, climbing the hills to escape, and subsequently spent nearly a month in exile in Chile, fearing for his life.

But the resistance continued in his absence, embodied by one of the few residents who refused to abandon Seque Jahuira. Sabina Quispe, a 57-year-old Aymara woman, is one of a handful of people still living in the contaminated community. She has stayed on her ancestral land with her two adult daughters and newborn grandson, determined not to leave despite knowing the land is poisoned. She tends to a few dairy cows, pigs, sheep, and a small potato harvest, struggling to maintain her livelihood in an environment that grows more toxic each year.

Surrounded by industry on all sides, Sabina harvests hay for her last surviving cows.

On the day of our visit, Quispe had constructed a roadblock of dozens of rocks, small and medium-sized, arranged in careful rows across the dirt road that passes in front of her house. It's her daily act of resistance against the industrial trucks whose dust coats her crops, animals, home, and gets in her throat. When the miners move her rocks, she puts them back. She carries a slingshot made from sheep's wool yarn—a traditional weapon that becomes deadly accurate in her practiced hands.

"I work hard, me and my kids. That's why we are doing well, thank God," she says, her voice trembling. "I've had enough of the invaders. I don't sleep, I don't rest at night. I work in my skirt, I sew. There's no time to delay."

From her perspective as one of the few remaining residents, Quispe describes how the mining companies initially tried to buy community silence with gifts—money for Christmas and Mother's Day, compensation payments divided among community members. "For different holidays they would always give us gifts," she recalls. Last year, community members received 3,000 bolivianos (about $430 USD) per person, she says.

The payments stopped when residents began complaining about contamination. "Once they noticed we weren't happy about it, they just stopped," Quispe explains. The message was clear: compensation was contingent on silence.

Quispe’s choice to stay has isolated her within her own community. Those who fled to find work in the city have accused her of taking money from the miners, questioning why she won't leave her poisoned land. The accusation stings because she has repeatedly confronted mining company representatives directly.

"I ran to the factory owners and they complained to me that I have to leave," Quispe recounts of one confrontation. When she demanded they stop sending trucks through the area because the dust was destroying everything, she says they told her, “‘I don't care. We don't care. You should just leave.’"

The cattle losses have been devastating. Quispe says that before, "each child would usually have 10 cows, but now they only have three." The contamination affects everything in her daily life. "When it floods, the water is red, black, and it floods all of this," she explains, pointing to the land that surrounds her. During the dry season, dust covers everything—crops, animals, her home. The smell that comes at night from the factories is overwhelming.

Yet, Quispe continues to farm and raise animals, administering veterinary injections to keep them alive. "I give them injections so they don’t fall back and die," she says. She stored food from harvests before the contamination worsened, preferring to eat those reserves rather than newly grown crops.

Renan Peña Fernandez and his mother Elena. Elena carefully offers her son a handful of “chuño,” an Andean potato. Even if they are contaminated, the Aymara people consider every food to be a gift from Pachamama, Mother Earth.

Her resistance is shared by others who have witnessed the transformation of their homeland. Renan Peña Fernández, a former community authority, speaks with passionate intensity about what has been lost. At 53, he has moved away from the community but returns regularly to help his 75-year-old mother, Elena, who still lives here and continues to harvest small batches of potatoes from the contaminated soil. Standing in a field where his mother tends her diminished crops, Fernández recalls a landscape that once teemed with life.

"This used to be more of a wetland here before the mining came and sucked all the water," he explains, gesturing toward the arid expanse. "We are actually above water—a meter and a half. It's like a wetland, but the company sucked all the water out."

The memories he carries are of abundance that younger generations will never know. "Ducks, really big aquatic birds like geese—we used to hunt them," he says. "Even flamingos used to be here. Sometimes, even last year in the rainy season, we got to see some flamingos, but nothing compared to previous years."

The real devastation began in 2006 when the university professor who bought the brick factory began experimenting with mineral extraction. "He started bringing this mineral, bringing other types, and then more miners started arriving. Then there were eight different people doing that, and they started bringing other types," Fernández recalls.

The pattern of deception was systematic. The miners expanded their operations by convincing community members to sell their land with promises of partnership. "They told them, you're gonna be a partner, so we're gonna give you money from what we do. The first years they would get some money, but eventually they stopped paying them," Fernández says.

Fernández says the mining companies began extracting without permission, a violation of Indigenous legal frameworks that require Free, Prior and Informed Consent. The environmental destruction has been total.

"It's not a choice that you have to eat," Fernández says when asked about consuming contaminated crops. His family still harvests potatoes, but like Quispe, they do so knowing the soil is poisoned. "The earth still wants to give life," he says with deep emotion. "But when it rains, it floods and pollutes the food, and [we] have to eat that food."

The cultural loss cuts as deeply as the environmental damage. "Your great-great-grandfather, your great-grandfather, your grandfather, your parents, your children—this is it. This is all we have left," Fernández says, his voice breaking.

Yet, even in the face of such devastation, Fernández speaks of resistance and hope. The community has developed plans for greenhouse agriculture using uncontaminated water from 70 meters underground. "We already have a project underway," he says, "but we don't have anyone to support us, anyone who can finance us. The State isn't interested because it wants to see us fail."

The greenhouse project would cost $10,000 for an 80-square-meter pilot facility—an endeavor that could begin to restore food sovereignty to the community.

"We're going to be ranchers again," Fernández says with fierce determination. "We don't want pity. We have dignity. We are capable of shaping our own destiny, just as our ancestors were. If we don’t resist, we'll disappear, and when we disappear, the Indigenous people will die. Technology won't feed what most people depend on: Indigenous people."

These warnings have begun to resonate beyond Seque Jahuira. On September 1, 2025, dozens of Aymara Indigenous people took by force the municipal building in nearby Viacha—the closest city to Carvajal’s community—demanding that the mayor, Napoleón Yahuasi, revoke the operating licenses of more than 20 mining companies causing contamination.

The protest began in the morning with confrontations between community leaders and a small group of police. It ended only when the mayor, under pressure, issued a municipal law with his seal and signature ordering the withdrawal of mining licenses. The law mandates that the mayor must manage the closure and mitigation of all mining activity, present a judicial compliance action, and revoke all operating licenses.

"Our animals are dying, our companions are sick. We want justice. We can no longer bear it. We don't want more mining activity, we don't want more factories, because they affect the countryside, agriculture, and water," community leader Narziso Canaviri told EFE news agency during the protest.

The demonstrators presented documents from the La Paz Governor's Office showing that in 2023 there were nine mining companies, legal and illegal, generating liquid waste, and that the number of companies rose to 23 last year. The reports mention "coarse sands in the tailings drying area," "overflow of acid water from sedimentation pools," and note that several companies lack a waste management plan.

Indigenous leader Amelia Paco says that the municipality has negotiated mining activity in Viacha "with Chinese and private companies [dedicated to] gold washing," despite the fact that this jurisdiction is not characterized by gold exploitation, but has an agricultural and livestock vocation. "There are gold washing companies. In the municipality we don't have gold. The companies bring soil from elsewhere because we have the rivers," she explains.

The victory in Viacha represents a breakthrough that Carvajal and his fellow defenders have long sought. The municipal law specifically addresses the contamination that has devastated communities like Seque Jahuira, where cyanide and mercury from mining operations have destroyed the water sources that once sustained both human and animal life.

Polluted water flows around the community.

A Pattern of Intimidation

The threats against Carvajal follow a pattern documented by Cultural Survival and other organizations tracking attacks on Indigenous defenders across Bolivia. The violence escalated dramatically after Carvajal began organizing resistance. Miners brutally beat his brother, leaving him injured and traumatized.

But the attack that most haunts Carvajal happened to his son on June 26, 2025. His son, who is 35, was severely beaten by miners. Carvajal keeps photographs from that night—images too disturbing to forget, his son's face swollen and bloodied from the assault.

The physical violence is accompanied by psychological warfare designed to break Carvajal's resolve. His phone rings constantly with calls from unknown numbers. When he answers, the callers either hang up immediately or stay silent on the line—a form of harassment meant to create constant anxiety and fear. Carvajal believes the miners are behind these calls, part of a coordinated campaign to intimidate him into silence. The calls come at all hours, disrupting his sleep and creating a perpetual state of vigilance.

During a community meeting in the town of Viacha last spring, the threats became explicit. When Carvajal spoke out against the mining companies, miners who were present told him directly: "You will pay for speaking out. You will vanish.”

The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre has documented specific death threats against the Seke Jahuira community, noting that community members face "persecution and death threats after denouncing the pollution caused by mining activity in the region."

In April 2025, Carvajal took his case to the international stage, traveling to New York to address the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. Accompanied by Cultural Survival, he presented his community's denunciations of extractive activities by foreign mining companies and illegal actors, as well as violations of their rights perpetrated against them due to their defense of their territories.

There, Carvajal faced harassment and intimidation. During his advocacy activities and denunciations of the Bolivian state's failure to protect his community, he was verbally threatened by a leader of the Single Trade Union Confederation of Campesino Workers of Bolivia (CSUTB), an organization that is part of the Unity Pact supporting Bolivia's ruling political party. He was also harassed for wearing his traditional clothing and for displaying the Bolivian flag during his intervention at the plenary session—behavior that other speakers engaged in without being approached by security guards.

Cultural Survival denounced these incidents, calling them "extremely concerning" and noting that "this type of intimidation and threats also [occurred] in a space such as the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in New York, a forum created by and for Indigenous Peoples, which should be a safe space for peaceful dialogue."

The Price of Resistance

The environmental cost of this mining boom is staggering. A 2024 report from the Environmental and Risk Management Office of the Viacha Mayor's Office revealed contamination of the Sarh well—a key water source for several communities—with cyanide, ammonia, and sulfate.

Carvajal describes a landscape void of life: "We knew how to keep fish here, tiny ones...there were also lizards. I knew all their colors, green, red, all the colors...now, there's not even a toad."

Despite the overwhelming evidence of environmental destruction and human rights violations, Carvajal's appeals for justice have met with bureaucratic indifference. He has sent letters to the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Environment and Water, and the Ministry of Mining—all without response.

"Three weeks ago he sent letters to different ministries, but they're not responding," his daughter says. The family believes the government's silence is intentional; they know about Carvajal's testimony to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and view him as a troublemaker.

Carvajal's next steps involve filing a lawsuit with Bolivia's Constitutional Court through a popular action, and if that fails, taking his case to the Inter-American Human Rights Tribunal. Bolivia has signed the Escazú Agreement and ratified ILO Convention 169, instruments that guarantee Indigenous Peoples' rights to Free, Prior and Informed Consent regarding projects affecting their territories.

Grief shadows every aspect of Carvajal's struggle. His wife, who he says was the first to confront the miners when the cattle began dying, died of cancer a year and a half ago. The loss has left him shattered, but resolute.

"As long as I'm alive, I'm going to face it. I'm not afraid. Even if they kill me—when they kill me—I'll have to rest. But as long as I live, I'm going to fight for my children, for my grandchildren, for those who come after me," he says.

The Lone Guardian of Memories

From her law office in El Alto, the Indigenous city that rises above La Paz, Beatriz Bautista works to defend communities like Seque Jahuira through Bolivia's complex legal system. The 52-year-old Aymara lawyer and philosopher has built her practice around supporting Indigenous communities confronting extractive industries, and she now represents Carvajal and others fighting the mining contamination in their territories.

Bautista’s legal education took place at Bolivia's first Indigenous university, which the Morales government shuttered in 2006. She earned her law degree with a focus on Indigenous Peoples' rights and co-founded the Qhana Pukara Kurmi association in 2018, which now provides legal support to over 100 Indigenous communities across Bolivia facing extractive pressures.

Bautista frames the current mining conflicts within Bolivia's long history of resource extraction. "As Indigenous people, we are pre-existent to all these colonial nations, [yet] the government has the power to take away our land from us and give it to international companies," she says. The pattern stretches back centuries: "All the silver was extracted and delivered directly to Spain, and that's why Europe became so rich—because all the minerals came from Bolivia."

For Indigenous communities, territorial rights represent survival itself. "The right to territories is key because any Indigenous people without their territory won't exist," Bautista explains. "The violation of these rights is attempting genocide against our own existence, against the generations to come." Her advocacy work has made her a target for the same forces threatening her clients.

"I have been hit. The government threatened our association, and they closed our office doors. The threats are constant. It's very difficult to access Indigenous territories because the miners know who we are," she says.

Despite constitutional protections and international treaties, Bautista argues that Bolivia functions as a colonial state that "won't acknowledge the rights of Indigenous people and their territories." Yet, she maintains her commitment to the legal fight. "Even if the miners have so much power, that doesn't mean we won't keep fighting," she says.

The story of Seque Jahuira reflects a broader crisis across Bolivia, where Indigenous leaders say economic pressures have made "the pressure on the territories more aggressive in terms of mining, hydrocarbons, and the advance of the agricultural and livestock frontier."

Bolivia's economic crisis, driven by declining natural gas revenues and a currency shortage, has pushed the government to rely increasingly on extractive industries for revenue. Mining cooperatives, which control 55% of mineral production, pay no royalties to the state because they are classified as "autonomous non-profit entities," leaving communities like Seque Jahuira to bear all the environmental costs with none of the economic benefits.

Visitors to the area are warned to "be very careful" because miners conduct surveillance on outsiders. "Just explore and observe the community, don't linger. It's dangerous," locals advise. The landscape carries an essence of lawlessness—a place where anything goes and traditional authority has been replaced by the power of extraction.

Carvajal now lives in a neighboring Indigenous community, forced to abandon his ancestral home as the contamination made it uninhabitable. He continues to visit Seque Jahuira regularly, a lone guardian of memories and traditions that predate the mining invasion. He says that he and fellow advocates are currently “being persecuted, threatened, and defamed through social media. The slander is just for defending the environment, the territory, the right to life, and water. We have no support or protection from anywhere.”

Cultural Survival and other international organizations continue to advocate for the protection of Indigenous defenders like Carvajal, calling on the UN and national governments to guarantee safe spaces for those who risk everything to protect their territories. But in Seque Jahuira, time is running out, and Carvajal knows that each day can bring justice, or disappearance.

--Brandi Morin (Cree/Iroquois/French) is an award-winning journalist reporting on human rights issues from an Indigenous perspective.

The writer visited several government ministry offices in Bolivia to request interviews, including the Ministry of Mining and Metallurgy, Ministry of Environment and Water, and Ministry of Cultures, Decolonization, and Depatriarchalization. Written interview requests were hand-delivered and officially stamped by ministry officials, a standard media process. As of this publication, no responses have been received from any government ministry.

Top photo: Pastor Carvajal, the village authority, testifies to the damage caused by the mine. In the background, the brick factory is in full activity.

READ PART 1: All Eyes on Bolivia: Indigenous Resistance in the Country's Mining Wasteland