By Brandi Morin (Cree/Iroquois)

Photos by Julien Defourny

When thousands take to the streets to defend their livelihoods and territories, the world needs to bear witness.

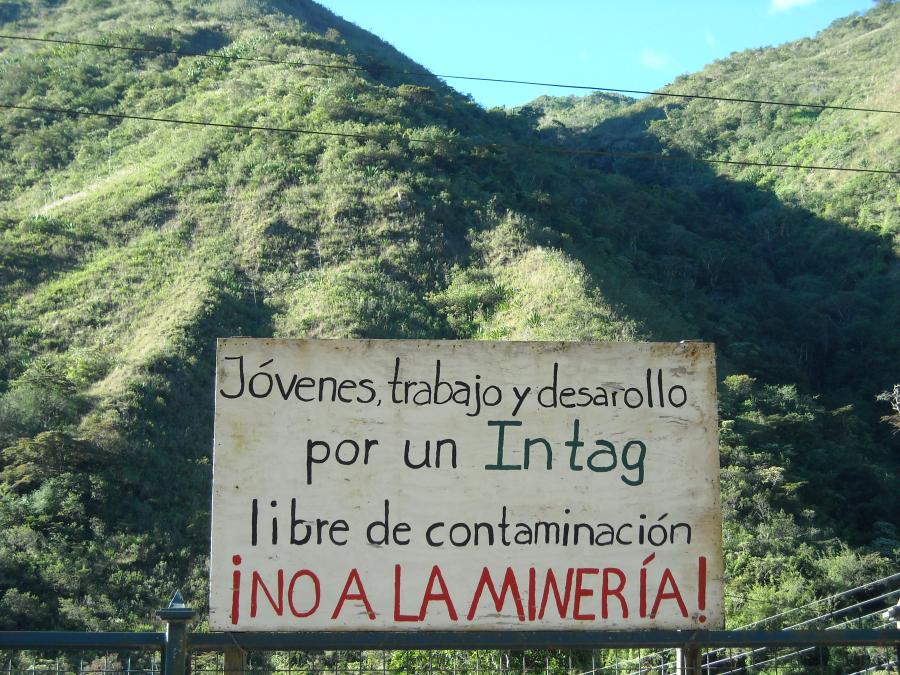

The plan was straightforward: travel to Ecuador's Intag region in Imbabura Province to interview a resistance leader who had successfully expelled a mining company from his territory. But on September 28, 2025, as my team and I prepared for the seven-hour journey north from our starting point, we quickly learned that nothing about covering social movements in Ecuador would be simple. El Paro—the national strike called by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE)—had transformed the country's roads into frontlines of resistance.

El Paro, which translates simply as "the strike," represents far more than a labor stoppage. It is a constitutionally protected form of collective action in Ecuador, rooted in the Indigenous right to resistance against policies that threaten their survival and territorial sovereignty. Called by CONAIE on September 22 following President Daniel Noboa's elimination of diesel subsidies through Decree 126, the mobilization united Indigenous communities, farmers, and social organizations across Ecuador's northern and central Andean regions in a coordinated uprising that would bring entire provinces to a standstill.

The diesel decree was merely the breaking point. CONAIE's demands encompassed the reduction of value-added taxes that had been increased months earlier, revocation of environmental licenses for extractive projects threatening Indigenous territories, an end to criminalization and persecution of land defenders, increased government investment in health and education, and justice for activists detained during mobilizations. Most urgently, they sought accountability for the murder of 46-year-old Kichwa land defender Efraín Fuérez from Cotacachi, who had been shot and killed by the Ecuadorian military on September 28 while protesting in Ilumán, Imbabura.

My small team consisted of photographer Julien Defourny, my Indigenous Shuar guard Numii Antun, interpreter Claudia Herrera, and social media producer Freddy Ankuash, also Shuar. We are journalists and allies committed to telling stories that mainstream media often ignores or misrepresents. What we encountered over the next four days would test that commitment in ways we hadn't anticipated.

Into the Blockades

After successfully passing through Santo Domingo, we aimed to reach Latacunga, south of Quito, for the night. Winding through high mountain roads as a breathtaking sunset painted the valley below with white, fluffy clouds, the scene felt like the calm before the storm. As dusk settled, a Kichwa farmer and his wife flagged us down for a ride to Latacunga. We made room in the van, joking with the woman about my English as night descended around us.

Then we saw the fires.

Dozens of bright orange flames appeared in the distance as we approached the final stretches to Latacunga. The acrid smell of burning rubber filled our nostrils as we slowed to navigate through crowds of people and parked vehicles lining the highway. When we could go no further, we parked and approached on foot.

Fallen trees, rocks, and tire fires blocked the road completely. Dozens of people gathered around the barrier, chanting and listening to voices amplified through megaphones about the strike. They encouraged each other not to stand down—this was about their future, about exposing President Noboa's corruption. The answer to our inquiry about passing through was a hard "no." Nothing and no one would cross. The Paro was serious.

Rumors began swirling through the crowd that the military was advancing up the hill to sweep the area and remove the blockade. Some people shouted, others ran; children played on the sidelines. Fear and anticipation charged the air. The military had been heavily enforcing the government's orders to quell protests and remove blockades, with reports of rights defenders injured by rubber bullets and tear gas. Anything seemed possible.

We decided to search for another route. The Kichwa farmer assured us he knew a back road. An English-speaking local Kichwa woman who had recently returned from studying in the United States asked to join us with her boyfriend, and suddenly we were packed like sardines in the van. We turned away from the chaos and disappeared into the night on a small dirt road leading high into the mountains.

In pitch darkness, through thick fog that made the ride treacherous and swerving, we maneuvered around fallen trees placed by protesters. The farmer lost his way for several miles before another local directed us to a route that eventually connected to a main highway. By 9:30 pm we arrived in Latacunga, only to find the central area blockaded by barbed wire fencing and police. Dozens of military personnel patrolled the mostly empty streets, preparing for an anticipated demonstration the next morning. We were warned: leave by 5 a.m. or risk being locked in until the protests were quelled.

The next morning brought an eerie silence. Peeking through my hotel window curtains, I saw the main square empty except for heavily armed military personnel in green suits with dogs, guns, and shields. Their blockade of the center was holding. Stores remained closed. Everything shuts down for El Paro.

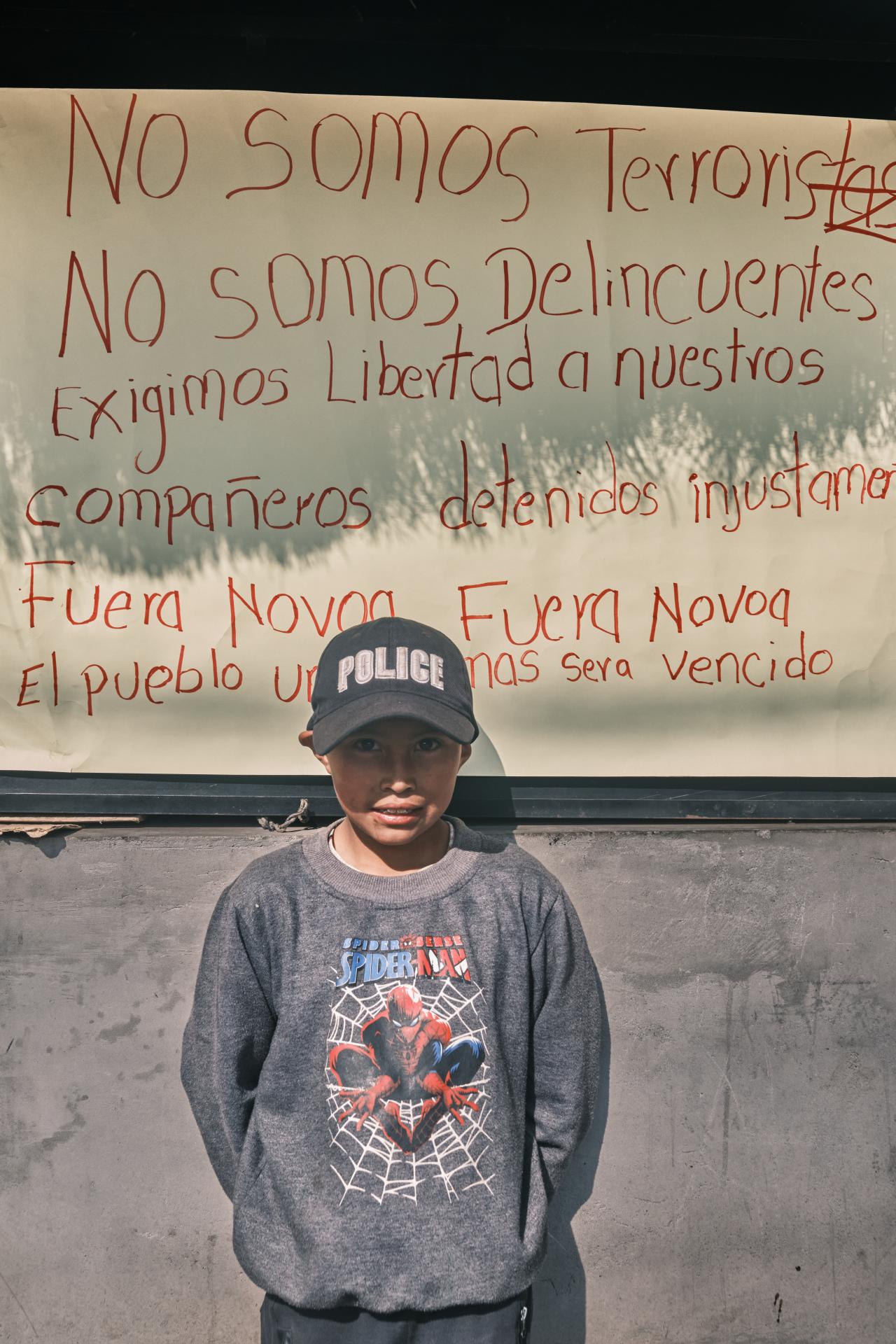

“We are not terrorists, nor criminals. We demand the release of our detained brothers. Get out, Noboa, get out. The people will never be destroyed.”

The Human Face of Resistance

After several more hours navigating roadblocks and hitching rides, we reached Las Cajas, a small town about 15 minutes from our destination of Otavalo. Large rocks, boulders, and fallen trees blocked the road completely. We would have to continue on foot, hoping the Kichwa crowd we heard rallying beyond the blockades would allow us through.

As we approached, suspicious eyes turned toward us, outsiders. I introduced myself as an Indigenous journalist from Canada and explained our team's mission. I asked if they would let us interview them—international attention to their crisis could help their cause. They are fighting for their rights against an apathetic and oppressive government, after all. They agreed, but first they wanted to show us something.

An elder woman in her 80s, no more than 4'11" and dressed in traditional clothing with a light gray fedora, gathered a pile of tear gas canisters and bullet casings in her hands—remnants from the previous night when the military had attempted to break up the blockade. Her voice rose with passion as she thrust the evidence toward us: "We aren't terrorists! We have one dead already, and others in prison. We want the government to release them, return them unharmed. We need support!" She dropped the canisters to the ground with a shattering noise. "They want to kill us with these. With this, tonight, they will kill us."

A Kichwa land defender in his mid-30s explained that they are not terrorists, that their region provides Ecuador with essential goods, including potatoes, beans, corn, chocolate, barley, wheat, lentils, onions, cheese, and yogurt. With rising gas prices, they simply want to afford to continue producing. Life is already hard enough. He described the government's violence against peaceful protesters as a violation of their rights: "Now they call us terrorists, but we are working people. Farmers, peasants. We are countryfolk with a lot of pride. We feel really outraged that they call us terrorists. We don't have weapons; we don't defend ourselves with anything. But they attack us with gas and bullets."

A woman who identified herself as a mother and grandmother added that the military's brutality was unnecessary. "We are demanding our rights as Indigenous Peoples. We will continue until our rights are respected and Decree 126, that they put it back into effect." The crowd went on to denounce Fuérez’s murder—their brother, they declared. "They killed him! So many are wounded, that's why we are in resistance. Please help us get this information out to the international community!"

A Night of Reckoning in Otavalo

Otavalo, known for having one of the largest Indigenous markets in South America, featuring textiles, handicrafts, and food, is home to the Otavalenos, an Indigenous Kichwa people fiercely proud of maintaining their cultural traditions, including traditional clothing and music. But the vibrant city we entered bore little resemblance to its reputation. Black smoke from various fires at roadblocks rose high in the air. It looked like a war zone.

The crowds manning the blockades and patrolling the roads represented all walks of life, young and old, even children. Some held sticks with sharp nails protruding from the top, for protection, they said. A young Kichwa woman wearing a blue plaid shirt, baseball cap, and glasses welcomed me in English. She thanked us for coming and begged us to help get the message out, describing what she had witnessed: "This is the main area where the military is coming. They are attacking us. We are trying to protect our rights, just that. They are coming with guns, with bombs. We are a community protecting the rights of all the people in Ecuador. You can see we are just women without any guns, with just my telephone to take pictures to reveal what the situation is."

When I asked what it was like to see her community turned into a war zone, emotion filled her voice. "It's really hard, especially for the children,” she said. “Last week, the military threw bombs in front of the school. It's affecting us psychologically, the mental health of the little ones. It's really, really hard."

We decided to stay the night, knowing the word on the street was that the military typically executed violence between 11 p.m. and 3 a.m. Around 5 p.m., alarms sounded in the streets—blowhorns and roaring crowds. The military had arrived. It was time to run toward the action.

My adrenaline surged as Numii and I reached the crowds. I made sure my press ID was visible on my jacket, though I wasn't sure it would protect me. What I witnessed took my breath away: literally thousands of people walking through the streets in procession, shouting for liberation and revolution. Then came the troops—rows of soldiers in green, flanked on all sides by the people, followed by army tanks, an excavator, and other armored vehicles.

We followed as day turned to night, reaching the brick blockade we had passed earlier. Indigenous leaders spoke passionately among themselves and decided to remove the blockade and allow the military to pass. The procession continued up the hill, where the resistance had erected a candlelit memorial for Fuérez, a mural of his image painted on a brick wall beside it.

Everyone stopped. People started yelling. Wails of grief cut through the air. The army personnel looked emotionless behind their masks as one woman yelled to them in tears: "He [Efraín Fuérez] is gone! And we don't get apologies like you said. Aren't you ashamed? Don't you feel any remorse? We are all God's children. Sooner or later, you'll face judgment from above. You'll pay for all the wrongs you've done!"

The crowds pushed forward, encircling the military. Tension built to a breaking point. Then, in a remarkable turn, a military commander stepped forward to speak into the megaphone. Facing the memorial, he said, "The passing of our brother, may the Lord keep him in glory and give strength to you, your family, and your loved ones in these difficult times. I deeply regret the passing of our friend."

The crowd breathed a collective sigh of relief. Minutes later, the procession continued, with roadblocks moved aside as it progressed. We were told they would walk to the next city, about a five-hour journey north. That night, no violence unfolded before our eyes—just a coming together of two sides, the crowds of resistance leaders and townspeople and the power and might of the military, walking side by side.

The road to Otavalo and the Colombian border is completely blocked. The people of every village are participating in the revolt.

The Bigger Picture

What we witnessed in those four days represents only a fragment of a much larger crisis. As of September 28, the Alliance for Human Rights of Ecuador had recorded more than 60 people detained and more than 40 injured. Other reports tate that 205 people were arrested, 287 were injured, 15 people were temporarily missing, and 2 people died. Of particular concern is the arrest of 12 people in Otavalo, including 10 Kichwa Indigenous people charged with terrorism—a charge that carries up to 30 years of imprisonment.

The Ecuadorian government's response extended beyond physical violence. CONAIE leaders reported that their bank accounts and those of many social organizations had been frozen without court orders. Community media outlets, including the Ecuadorian Telecommunications Regulation and Control Agency and the channel of the Indigenous and Campesino Movement of Cotopaxi, faced censorship. Power cuts and internet blockages were reported in Cotacachi and Otavalo in an attempt to cut off communication.

According to Amnesty International, this deterioration of human rights in Ecuador under President Noboa's administration includes "attacks on the Constitutional Court, which put judicial independence at risk, and the lack of cooperation by the armed forces in investigations being carried out by the Public Prosecutor's Office into dozens of enforced disappearances that occurred in 2024." Ana Piquer, Americas Director at Amnesty International, stated, "The repression of protests, attacks on the Constitutional Court and the persistence of a militarized security strategy, despite serious human rights violations, place Ecuador on the list of countries in the region that are experiencing a worrying rise in authoritarian practices."

The fuel price increase that sparked the Paro—from $1.80 per gallon to $2.80—particularly affects Indigenous people who work in Ecuador's crucial agricultural, fishing, and transport sectors. President Noboa argues that the government needed to slash the $1.1 billion subsidy to shore up the country's finances and combat fuel smuggling across Ecuador's borders into Colombia and Peru. But for communities already struggling to survive, this economic rationale rings hollow against the reality of their daily hardships.

The protests are not occurring in isolation. They are part of Indigenous Peoples' ongoing defense of their territories against extractive industries and “green energy” projects. In the southern province of Azuay, communities have been demanding the revocation of a mining concession in Kimsakocha and the halting of mining projects in the páramos. Communities along the Yanuncay River are also demanding the cancellation of the Yanuncay-Soldados Hydroelectric Power Plant Project, as it will be built about an hour from the Kimsakocha to provide power and water to mining projects. The government's threat to reopen oil bidding in the Amazon represents yet another assault on Indigenous territories and the environment they have stewarded for generations.

Before leaving the city of Otavalo, indigenous groups prepared a surprise for the military to commemorate the death of the indigenous leader who was assassinated a few days ago. The banner proclaims: “We are the resistance, not terrorists.”

Why This Matters

Our journey back to retrieve our van—what should have taken half an hour stretched to nearly seven hours of walking and hitching expensive motorcycle rides—gave us time to reflect on what we had documented. Not many days after we left, violence in Otavalo and nearby cities and towns erupted between the military and protesters. The prisoners were eventually released, but the situation continues to escalate with no signs of either side relenting.

As an Indigenous journalist, I understand that these are not just stories—they are the lived experiences of our relatives fighting for survival. The international community must recognize that what is happening in Ecuador is not isolated civil unrest, but a systematic attempt to silence dissent and crush Indigenous resistance to extractive capitalism.

The diesel decree was merely the final straw. CONAIE's demands address systemic issues: reduction of value-added taxes, revocation of environmental licenses for extractive projects, an end to criminalization, increased investment in health and education, release and justice for detained activists, and accountability for Efraín Fuérez's murder. These are not unreasonable demands—they are fundamental rights recognized in both the Ecuadorian Constitution and international instruments, such as ILO Convention 169 and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The woman in Otavalo begging us to help get the message out understood something crucial: international attention can provide a protective shield for those resisting on the ground. When the world watches, governments must answer for their actions. When the world remains silent, impunity flourishes.

As Cultural Survival, the Indigenous-led organization I work with, stated in our response: "We stand in solidarity with them, support their struggle, and demand that the Ecuadorian government cease fire and respect their fundamental rights. We call for a dialogue free of violence in which the Ecuadorian authorities listen to the demands of Indigenous Peoples in defense of life and the environment, and guarantee their rights."

The 80-year-old woman holding those tear gas canisters, the young mother worried about her children's mental health, the farmers defending their livelihoods—these are not terrorists. They are people fighting for their right to exist, to maintain their cultures, to steward their territories, and to have a say in decisions that affect their futures. Their resistance is an act of survival, and their voices deserve to be heard.

As we witnessed that remarkable moment when the military commander apologized at Fuérez's memorial, I was reminded that even in the midst of state violence, humanity can break through. However, one moment of recognition does not undo systemic injustice.

On October 14, another young Kichwa man demonstrating in the Paro in Otavalo was shot in the chest by the military. Jose Guaman, 30, father of two children from the Cachiviro community, was airlifted to a hospital in Quito, but soon died of his injuries. The true cost of the Paro is alarmingly telling.

The international community—from human rights organizations to foreign governments to everyday citizens—must maintain pressure on Ecuador to uphold its obligations. Economic policies cannot be imposed without consulting those most affected. Environmental destruction cannot continue in the name of development. Indigenous Peoples' rights are not negotiable.

El Paro continues because the fundamental issues remain unresolved. As long as Indigenous communities face threats to their territories and livelihoods, as long as their demands are met with tear gas and bullets rather than dialogue, they will resist. Because for them, resistance is not a choice. It is survival.

--Brandi Morin (Cree/Iroquois) is an award-winning journalist reporting on human rights issues from an Indigenous perspective.