Over the past six months, Indigenous journalist Brandi Morin has travelled repeatedly to Ecuador, reporting on the impact of Canadian mining projects on the Indigenous Peoples who live there. In February, she spent time with the Shuar people, whose ancestral territory is threatened by a Solaris Resources copper mining project.

By Brandi Morin (Iriquois, Cree)

In the eastern shadows of Ecuador’s Andes mountains, where the dense Amazon rainforest begins its sprawl toward the horizon, the Maikuaints Shuar stand at a crossroads of survival.

Their pristine territory, covering 8,500 hectares and home to 430 people, has sustained their ancestors for millennia. Today, however, it faces an existential threat from Solaris Resources, a multinational mining company based, until a few months ago, in Vancouver. Solaris is eager to extract copper from beneath the soil that the Shuar consider sacred.

On a humid February morning in the town of Limon Indanza, president of the Maikuants Shuar tribe, Domingo Antun is in court facing charges of kidnapping — a crime he insists he never committed. As the leader of the Maikuaints community, Antun is responsible for protecting his people’s territory and maintaining order. It’s a duty he takes seriously, even as it lands him before a prosecutor.

“The legal text [court documents] clearly outlines the actions taken by the Indigenous guard community to stop the military,” Antun explains after his court appearance. His voice is steady, unwavering. The charges stem from an incident where Shuar Indigenous guards detained eight military personnel who had entered Maikuaints territory without authorization during the night of February 4th.

The military claim they were conducting “special reconnaissance” to verify reports of armed civilian personnel and illegal mining. The Shuar, however, saw something more sinister — preparation for their eventual displacement to make way for industrial copper mining.

What Ecuadorian authorities label as “kidnapping,” the Maikuaints view as a legitimate exercise of their constitutional rights. Under Ecuador’s constitution, Indigenous peoples are granted territorial autonomy and self-governance. As Antun explains, outsiders — even military personnel — must officially notify community authorities before entering Shuar land.

“When people come from outside, they must formally notify us, the authorities, so that we can gather information and subsequently notify the community,” Antun said. “The community must authorize any particular individual before they can enter and carry out any activities.”

This sovereignty isn’t merely claimed — it’s enshrined in law. “The Constitution guarantees that we are an autonomous people, entitled to self-determination and self-governance within our territory,” Antun asserts. “We define ourselves, which is why we have full protection and all necessary permissions. We have all the guarantees, provided by the State’s Constitution, as well as international protection.”

For the Maikuaints, the detainment of unauthorized military personnel wasn’t kidnapping but rather the enforcement of their territorial rights — a duty they take seriously through their Indigenous guard system, which maintains 24-hour vigilance over their ancestral lands.

This isn’t merely a legal dispute but a fight for cultural survival. Their community lives in harmony with the land, harvesting what they need, eating what they grow. Their relationship with the territory transcends Western concepts of ownership — it is spiritual, ancestral, and fundamental to their identity.

“What bothers us,” Antun says, his eyes narrowing slightly, “is that mining companies are (protected by) military patrols, and military personnel execute government orders.” The connection between extraction interests and government force is not lost on the Shuar leader.

As morning light streams through the windows of the courthouse, Antun prepares for the three-hour journey back to Maikuaints. The legal battle is just one front in a larger struggle. Back home, the community is preparing to defend what is theirs — peacefully, if possible, but with determination regardless of the cost.

“I will continue to face these allegations until the end,” Antun declares, his voice gaining strength. “I’m not giving up. With more strength, with more will, I will continue to protect my community and my territory from what we are facing.”

A reconnaissance mission on the frontier

Meanwhile, deep in the jungle of Maikuaints, three land defenders move silently through dense foliage. Numii Antun, Freddy Ankuash, and Kawarsito Chup Tseremp have painted their faces with ceremonial black pigment — a practice inherited from their ancestors that they believe provides strength and protection. Their destination lies at the edge of their territory, where it meets the neighboring Shuar community of Warintz, just a few kilometers away.

“We remain silent, ok?” Numii whispers, raising his hand to halt the group. “We’re standing at the boundary of the mining area. So, we stay quiet.”

They are on a reconnaissance mission to witness firsthand the progress of Solaris Resources’ copper exploration project. Though still in the exploratory phase, the mine has already extracted something precious — the unity between once-allied Shuar communities.

“We’re caught between two lines: our own frontier and that of the mining zone,” Numii explains softly. “That’s why we want everyone to stay silent.”

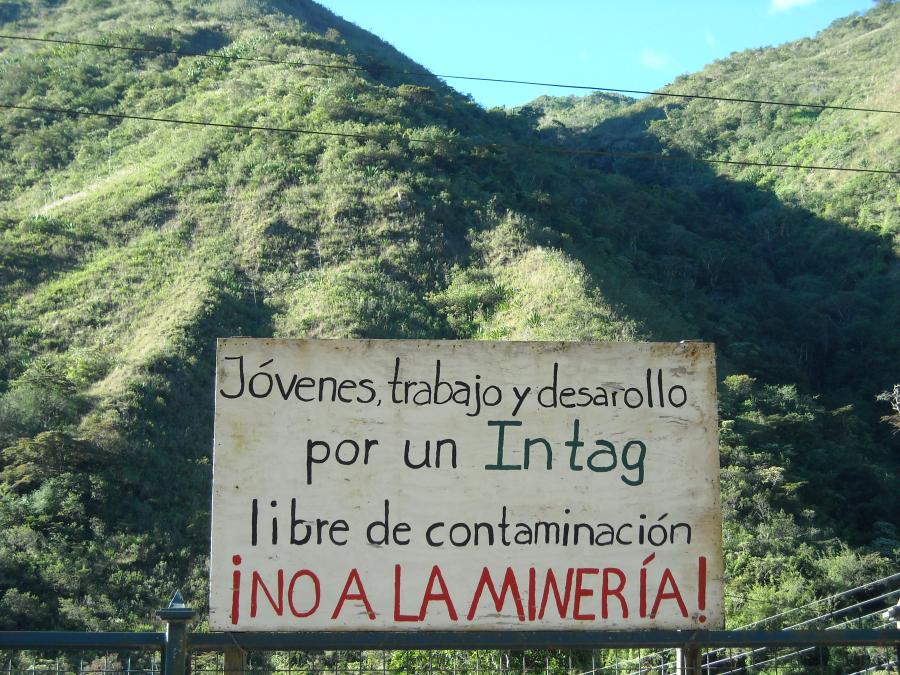

Under Ecuadorian law and international standards, mining projects affecting Indigenous territories require free, prior, and informed consent. For the Shuar people, this means the unified agreement of all 47 Shuar communities that form their nation. Yet Solaris and the Ecuadorian government have strategically bypassed this collective decision-making process, instead striking individual deals with just two communities — Warintz and Yawi — while excluding the others.

The Maikuaints, for their part, insist that no financial compensation could ever justify surrendering their ancestral home. What the mining company presents as economic opportunity, they see as a Faustian bargain that exchanges short-term gains for the permanent loss of something irreplaceable.

The classic divide-and-conquer strategy employed by the mining company has been painfully effective. The Warintz community next door, lured by promises of economic prosperity, has aligned with Solaris, while the Maikuaints — deemed outside the “impact zone” despite being within three kilometers of the mining site — have been excluded from negotiations and benefits.

Now, the Warintz Indigenous guards, once brothers in the same struggle, can be seen patrolling the boundaries, watching for those who might oppose the mining operations.

These three defenders know the risk. If they are spotted, or if they inadvertently cross into Warintz territory, they could be captured and detained. Still, they push forward through the thick undergrowth, determined to reach a vantage point that will allow them to assess the mine’s advancement.

After hours of careful trekking through steep jungle terrain, the sky darkens prematurely. Rain begins to fall, quickly becoming torrential — a common occurrence in this cloud forest region. With practiced efficiency, the three warriors construct a shelter from broad leaves and branches. They sense the downpour will continue for hours, and with darkness approaching, they make the difficult decision to turn back.

Later, they obtain drone footage of the mining area. The images reveal a stark contrast to the lush green canopy that surrounds it — a swath of bare, brown earth carved into the slopes of the Cordillera del Cóndor. The scars of exploration are already visible, hinting at the more extensive damage to come if full extraction begins.

These three defenders know the risk. If they are spotted, or if they inadvertently cross into Warintz territory, they could be captured and detained.

Numii views the footage with concern. “Since they don’t manage the environmental impact properly, all mining waste should be removed, not dumped,” he explains, referring to an area on a tall mountain plateau, where the company is disposing of old mining equipment. “This happens because they lack the capacity to take back the materials they no longer use, so they just discard them here.”

“I believe the right thing (for the company) to do is to take back everything they bring from outside, because that doesn’t belong to us.”

These images represent more than just environmental degradation — they foreshadow the destruction of the Maikuaints way of life. Where the mining company sees copper and profit, the Shuar see the slow death of ancestral waters, medicinal plants, hunting grounds, and ultimately, their cultural identity.

Canada’s tarnished reputation

As copper prices surge globally and Ecuador seeks to expand its mining sector, the Maikuaints find themselves on the frontline of resistance. Despite constitutional provisions requiring free, prior, and informed consent for projects affecting Indigenous territories, Solaris Resources appears determined to move forward with exploitation.

The plan is to rip open 268 square kilometers of pristine Amazon jungle for copper extraction. Ecuador’s government fully backs the project, despite its constitution being the first in the world to grant legal rights to nature itself.

In 2024, the International Labor Organization confirmed the Shuar’s persistent claim — that they were never properly consulted about this mining project, a clear violation of both international law and Ecuador’s own constitution.

Behind Solaris Resources lies a troubling history. The company, formerly Canadian-owned, strategically relocated its headquarters to Switzerland on January 1, 2025, after the Canadian government blocked Chinese investment in the firm. This move opened doors to massive Chinese financing, while maintaining connections to Canada — long considered the hub of global mining, with a reputation for wreaking environmental havoc on Indigenous communities worldwide with minimal regulation.

The company’s new CEO, Matthew Rowlinson, brings his own concerning background as a former copper executive at mining giant Glencore — a corporation with an extensive record of environmental damage and human rights abuses across multiple continents. While now leading Solaris, Rowlinson has maintained his Canadian ties as a co-founder of Moranda Metals, a Vancouver-based company seeking to exploit mineral resources across South America. The choice of Canada as a headquarters was strategic — the country’s notoriously weak international mining regulations make it the jurisdiction of choice for extraction companies seeking minimal oversight.

Devastation looms over the Shuar homeland. Across South America, the pattern is painfully clear: similar mines have transformed crystal-clear rivers into toxic orange streams laden with heavy metals. Lush forests have become barren wastelands. Indigenous communities face not just physical displacement, but illness and cultural annihilation.

Antun believes the company’s ultimate goal is the complete eradication of his community. For the Maikuaints, their territory represents not just land but also their cultural heritage and future — there is no alternative homeland for a people whose identity is inextricably linked to this specific place.

This ancient jungle has sustained the Shuar since time immemorial. Its rivers carry not just water but ancestral wisdom — each current a living thread connecting elders to children, past to future. Once poisoned by mining waste, these sacred waters and the generations of knowledge they hold will disappear forever.

Traditional knowledge and scientific resistance

But the fight to protect their homeland extends beyond legal battles and direct confrontation. Here, traditional knowledge and modern science intertwine in a strategic effort to halt the mining project.

“Our territory is rich in biodiversity,” explains Numii, picking a leaf from a nearby plant and scrunching it before passing it to a visitor. “It’s good for opening up the airways,” he notes. “So, with the passing of time, it won’t disappear, and future generations can preserve it as we are doing now. Our goal is for the world to see and appreciate everything we have here.”

The community has embraced a proactive approach, training some of their members as paraecologists to document endangered species across their territory. These efforts aim to create scientific evidence that might convince authorities to protect the area from mining development.

“Once, in this place, we found the Atelopus frog, which is a well-known species around the world,” Numii says, his voice filled with pride. “Right now, this frog is in danger of extinction because of mining.”

This fusion of traditional knowledge and scientific documentation represents a strategic adaptation in their resistance. “It’s one more strategy that could help us defend our territory,” Numii explains. “It would give us another chance to expel the company from this territory. And for us it’s good news and we are very happy. In that way we could defend it in a peaceful way.”

As he leads the way deeper into the forest, Numii stops to point out a peculiar plant emerging from the ground. “In Shuar we call it: Ihiach,” he says. It starts as a worm, “and when it dies it doesn’t transform into a butterfly. But as time passes, when all the habra dries up, roots begin to grow, and it transforms into a plant. Its roots are very beneficial, as many people claim, for treating cancer.”

These medicinal plants represent just one aspect of the rich biodiversity at stake. About forty minutes from the main community, Maikuaints elder Angel Nantip guides us to a sacred waterfall known as the Children’s Waterfall. Waterfalls are where the Shuar believe they can connect directly with Arutam, their God.

“For our culture, waterfalls mean the renewal of energies,” Nantip explains. “Our elders used to tell us that spirits inhabit the waterfall, protecting our lives. That’s why we rely on them and don’t want to destroy them, because if we destroy the waterfalls, the spirits will die, and we will lose our strength to keep fighting.”

These sacred sites — from waterfalls where ceremonial cleansing takes place to ancient caves once believed to house anacondas — form a spiritual landscape that cannot be replaced. They represent not just biodiversity but cultural heritage that the Maikuaints are determined to document and defend.

“It is our wisdom; the waterfall is sacred to us,” Nantip continues. “It’s the place where the sacred spirit dwells.”

The Maikuaints stand at the precipice of forced displacement — the latest chapter in a centuries-old story of dispossession in the name of progress and profit.

Scientific documentation of endangered species and cultural mapping of sacred sites serve as complementary strategies in their multi-faceted resistance against the copper mine. By cataloging what stands to be lost, they hope to demonstrate to the wider world that what’s at stake is irreplaceable — not just for them, but for all humanity.

As the sun sets over the Cordillera del Cóndor, the Maikuaints face a reality that Indigenous peoples around the world know too well: the encroachment of extractive industries caring little for ancestral rights or sacred connections to land. Solaris Resources’ copper exploration project marks the beginning of what could become a catastrophic transformation of their very existence.

“We are ready to defend our territory at all costs,” Antun says, his voice resolute. “Our ancestors protected this land with their blood, and we are prepared to do the same if necessary.”

The Maikuaints stand at the precipice of forced displacement — the latest chapter in a centuries-old story of dispossession in the name of progress and profit. The pattern is painfully familiar: divide communities, extract resources, and displace people whose connections to the land stretch back millennia.

Yet as the mine advances toward their territory, the Maikuaints remain unbowed. Through legal challenges, scientific documentation, cultural preservation, and if necessary, physical resistance, they have vowed that their community will not quietly disappear into history. Their struggle is both uniquely their own and part of a global Indigenous resistance against the forces that would reduce sacred homelands to mere coordinates on a mining map.

“This is not just about the Maikuaints,” explains Numii. “This is about all Indigenous peoples facing the same threats. If we lose here, others will lose elsewhere. We fight not just for ourselves, but for all who defend the Earth against those who would destroy it for profit.”

As night falls over their territory, the Maikuaints continue their vigilance, their ceremonial fires burning as they have for countless generations — a defiant light against the encroaching darkness of displacement and extraction that has claimed so many Indigenous homelands before theirs.

Photos by Julien Defourny. Julien is a Belgian photographer and documentary filmmaker committed to sharing the voices of people and ecosystems often overlooked.