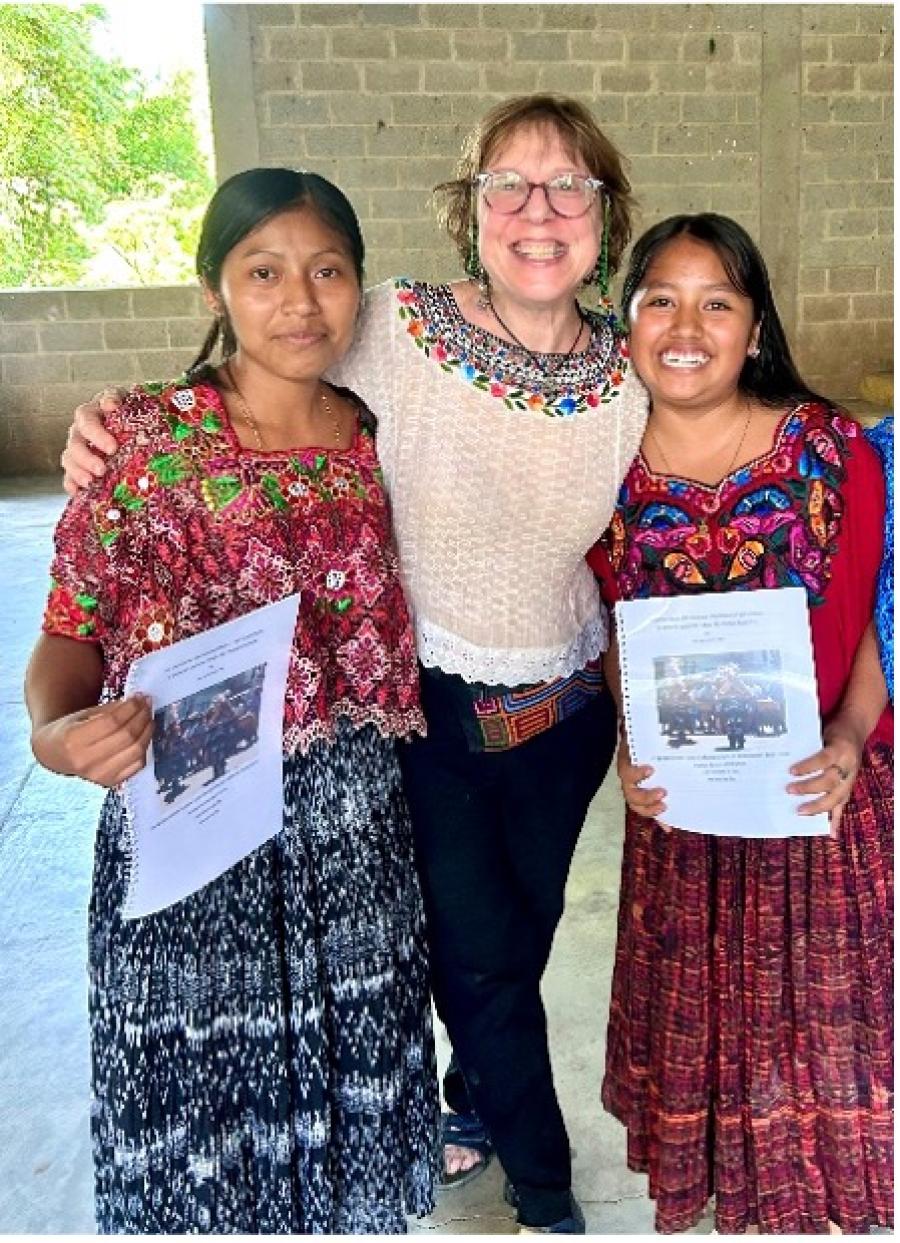

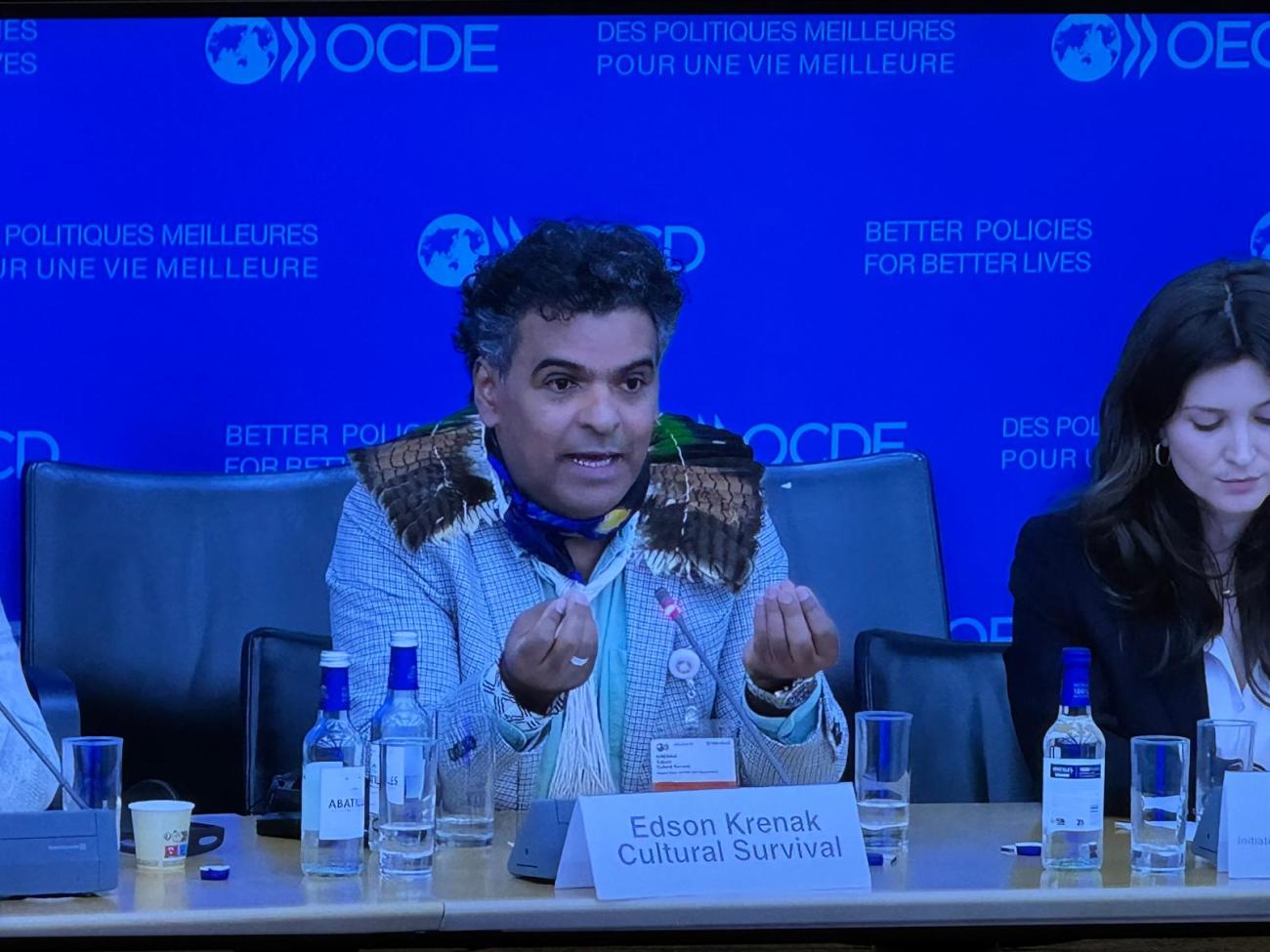

By Edson Krenak (Krenak, CS Staff)

On May 4–8, 2025, Cultural Survival and the Securing Indigenous Peoples Rights in the Green Economy (SIRGE) Coalition participated at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains in Paris, France. A delegation of Indigenous representatives and allies coordinated some advocacy efforts to highlight the impacts of the global transition mineral boom, particularly for electric vehicle (EV) batteries, on Indigenous lands, rights, and ecosystems.

Our advocacy brought together Indigenous and Quilombola voices from Brazil, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Sweden to raise awareness among key stakeholders, including investors, automakers, financial institutions, and policymakers. The goal was to center Indigenous leadership in discussions on responsible sourcing and due diligence in mineral value chains and mobilize real changes in the landscape. We understand that the mineral supply chain is part of an economic model that needs to be transformed to protect Indigenous communities and the biodiversity of the planet.

Key messages

The extraction of minerals for electric vehicle batteries has been increasingly associated with violence and conflicts, deforestation, water scarcity, and violations of Indigenous Peoples’ rights across multiple regions. As Djalma Ramalho Gonçalves (Aranã Caboclo) puts it: “There is a stain of indigenous blood in the EV battery.”

Ethical behavior and systemic accountability are required: not just from mining companies, but also from investors, insurers, automakers, and financial backers who profit from these extractive practices and sustain this abusive and endless extractive model.

Indigenous people are calling for establishing no-go zones (like water sources, bodies, and sacred sites), adopting binding Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) legislation, and stronger protections for rivers, forests, and Indigenous communities affected by mining. Rivers and forests are the heart and veins of human life. We must protect them!

In a closed-door session titled “Closing the Gap: Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Due Diligence in Transition Minerals’ Value Chains,” organized by the SIRGE Coalition and the Raw Materials Coalition, the dialogue focused on how current due diligence frameworks can better reflect the rights and needs of Indigenous communities and fix bad practices by the supply chain, especially upstream.

The OECD also organized a well-attended session entitled “Strengthening Local Voices in Mining: Insights from Indigenous Peoples in Mining Regions”. This session amplified ground-level experiences from mining-affected communities and highlighted demands for stronger protections and community-led oversight. My main message was about how Indigenous Peoples have been preparing themselves and their institutions to sit at the table of decision-making processes that impact them directly and indirectly. We Indigenous People are taking the step forward because the industry and governments have failed the planet, have failed our rights, have failed to create an inclusive and truly democratic environment for a better society and a better Future. The slogan “The Solution Is Us,” coined by Indigenous Peoples in Brazil, is about the stewardship of biodiversity, the protection of forests, rivers, deserts, and biomes that are the pillars of life and healthy environments for all. Indigenous Peoples are champions of this work. Even though we represent roughly 6% of the world population, Indigenous Peoples can do great things. We call on governments and corporations to partner with this minority to do truly great things. For that, Indigenous people must be at the forefront of, on the boards of directors, not only at events, but also at the policy-making level and leading environmental transformational practices in society.

Djalma Ramalho Gonçalves (Aranã Caboclo)

We also attended a presentation of the Colombian Traceability Treaty proposal (see more here), where we advocate for the full participation of Indigenous leaders and indigenous communities in this mechanism. The proposal for a binding global treaty on traceability for critical (sic!) minerals was launched by the Colombian government at the 2024 UN Biodiversity Conference in Cali, Colombia. The goal is to ensure a global pact is ready to be signed by November 2025 (in the COP Conference in Brazil). Still, again, without Indigenous Peoples, this treaty will be sequestrated by corporations and managed by groups that have historically not done a good job.

Djalma Ramalho Gonçalves, Angela Souza do Quilombo Mutuca (Quilombola), and I organized a peaceful protest at a car factory to call attention to the environmental and human rights impacts of “dirty batteries.” Led by the young Ramalho Gonçalves, the message aimed to question the narrative of false clean or green solutions.

One of the key moments was the panel presentation: “EU Electric Vehicle Targets: Assessing Human Rights Implications, Deforestation Risks and Industry Readiness”, hosted by FERN and RainForest Foundation, where findings were shared from a study by Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU Vienna) and commissioned by Fern and Rainforest Foundation Norway, linking EU EV demand to potential global deforestation and Indigenous land impacts through 2050, especially in Brazil and Indonesia.

Indonesian leader of the environmental group Satya Bumi highlighted the ecological degradation and social harms caused by nickel mining, particularly on Kabaena Island − a small island of just 891 km² now home to 15 mining permits covering 655 km². She also pointed out the links between mining and wars by asking, “Is it true that our nickel and stainless steel are used for the energy transition, and not for war or occupation?” From Myanmar to Brazil, the messages were similar. “Those who profit the most are rarely the ones who take responsibility.” We denounced the lack of corporate accountability and environmental restoration efforts (Additional source)

In a closed-door multisectoral dialogue, we discussed why history matters: “Mining, Indigenous Peoples, and the Potosí Principle.” Delivered by one of our representatives, this talk traced the historical continuity of resource extraction and inequality legacy on Indigenous territories and its modern-day manifestations, repeating the past mistakes, crimes, and destruction.

The 2025 OECD Forum reaffirmed the urgency of integrating Indigenous rights and leadership into global supply chain governance. Our presence in these spaces is essential to shift narratives—from profit-driven mining to people- and planet-centered accountability. We need an indigenous form to interact with the planet, not as a source of resources, but as our home, an extension of our lives.

Going forward, we will continue building coalitions, strengthening advocacy, and demanding mechanisms that genuinely protect Indigenous territories and uphold our right to self-determination.

Indigenous Peoples, Due Diligence Mechanisms and the Role of OECD

With SIRGE, Cultural Survival participated for the third time in the OECD Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chain. We were the first Indigenous-led organizations to participate and discuss what is happening on the ground with automakers, investors, insurance companies, and miners.

Many corporations have a clear message about the importance of engaging with Indigenous Peoples and respecting their rights in their policies and public commitments. Still, on the ground, things are very different. The OECD provides policy documents to guide countries and corporations to improve their work. For example, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas, and other resources, help companies meet expectations on due diligence laid out in the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Besides the National contact points, a kind of mechanism for good practice and conduct, OECD guidance (interactive Due Diligence Guidance) has become the leading international and industry standard that provides detailed recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices.

The image above displays some stakeholders that interact with Indigenous communities, like road transport companies, trading houses, automakers, electronics factories, and the first one, the mine -- all sectors have committed to following OECD Guidelines. When these policies support upstream (mining), midstream (processing), and downstream (manufacturing) industries work together they get investments and support from governments, banks and other investors making the landscape at the same time very complex and very challenging for Indigenous communities, impacted by those activities, to seek justice, protection and solutions for problems such as water access, food security and environmental harm.

Since the advent of the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factor, carbon footprints, and trade-friendly supply chain locations have become increasingly important because consumers want to have fair products not linked with human rights violations, child labour, slavery, environmental harm, conflict, and negative impacts on Indigenous Peoples. Downstream companies want ethical, low-carbon sources for their inputs and want to show it.

This map from the OECD website highlights the countries and regions that have committed to implementing and complying with the OECD Due Diligence Guidance.

The History and Context of the Forum

The OECD Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains was formed by a partnership between the OECD, the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), and the United Nations Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of Congo some years ago. It brings together governments, companies, civil society, and communities to address the issue of making mineral supply chains more responsible and sustainable, particularly in places affected by conflict, exploitation, and environmental harm. However, due to the low participation of Indigenous Communities and organizations, their message and their will were, like on the ground, silenced.

Since 2011, the Forum has worked to secure stronger protections for businesses and communities, including preventing child labor, ensuring the rights of artisanal miners, improving law enforcement, and more. The Forum is trying to align mining with environmental objectives, gender justice, Indigenous rights, and the worldwide energy transition. For that, it holds in-person and virtual events spanning entire continents. It held its in-person gathering of over 700 participants in 2018. In 2021, it held a virtual event reaching across borders. The Forum for itself has evolved—and with it, the opportunities for Indigenous communities to settle up and shape the conversation occurring on a global scale. IN 2025, though, the participation limitations are an obstacle for communities and civil society.

In the previous three Forums, Cultural Survival joined and brought leaders and representatives of Indigenous communities to speak powerfully about how extraction affects their cultures and territories. It is growing the understanding that due diligence can't just be a corporate checkbox—it must signify genuine accountability, with informed consent and a place at the decision-making table. The Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) cannot be reduced to a consultation. It is a robust and patient process that leads to a consent or not. Indigenous peoples have their governance systems that must be respected and protected in this process - FPIC is not driven by individuals, but by collective engagement.

Why Get Involved With — and For — a Responsible Mineral Supply Chain?

Indigenous communities have felt the effects of mining on our lands since the 1400s, when colonial powers started these activities. Many researchers call this pattern the Potosí Principle, named after Potosí, a city that once served as a key mining center for colonial empires. This idea shows how extracting minerals has long been linked to five problems: harm to the environment; military control; forced work; widespread violations of Indigenous Peoples' rights; keeping wealth, tech progress, and luxury going in far-off colonial centers, leaving destruction, inequality, and poverty behind.

Therefore, a responsible mineral supply chain values our Peoples and perspectives, advocates for our rights, guards our lands, and protects our waters and sacred sites.

Mining companies often lead the way into Indigenous territories but they don't work alone. They have support from a network of money people, rule makers, big businesses, and industry investors who back, excuse, and push these activities. The damage from mining is clear: from poison waste in storage dams to long-lasting soil and water pollution (the legacy of the tailings), from the lack of proper talks to ongoing social and cultural harm. The complexity of the mining landscape offers a way for government agencies to give out permits without approval and proper, robust FPIC from the communities.

When we participate at the OECD Forum, we make room to restrict, stop, or even fix mining's harm. We raise awareness, record damage, and call for fairness—not just for our communities now but for those to come. not just for those who do not want to see mining in their lands but those, like my own people in Brazil, who are struggling with the mining presence and its harmful legacy.

A responsible mineral supply chain can't happen without Indigenous People leading the way. We have cared for our lands and living beings for hundreds of years. Now, our ideas must guide what's next.