Indigenous communities in western Canada are reclaiming their ancestral belongings and bringing the spirits of their ancestors back to the communities where they once lived. Efforts to return ancestral remains and cultural belongings from external museums began in the late 1970s, but only in recent years have truly collaborative relationships between First Nations and museums developed.

Located within the unceded, ancestral territories of the xwməθkwəyə’ m (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, the Museum of Vancouver (MOV) is one of Canada’s premier institutions of civic history, where hundreds of items from many First Nations across British Columbia have been held. It was not until 2006 that the MOV developed a rematriation policy for its Indigenous collections, committing to: “The return of human remains and directly associated burial Objects, upon the request of an Indigenous individual, family or community with a demonstrable claim of a historical relationship to those materials in question or as a result of the MOV’s own initiative; The return of Objects that may have been acquired under circumstances that render the MOV’s claim invalid, at the request of a governing body, community, organization or individual; The return of material culture of spiritual significance or essential to cultural survival; and The adoption of shared Custodial Arrangement Agreements or Loan Agreements in lieu of repatriation agreements, where appropriate.”

Every qatŝ'ay is unique in the combination of designs and motifs.

Since then, many Indigenous Nations have been advocating for recovering their own ancestral artifacts and requesting rematriation processes. Although the Museum of Vancouver has implemented this policy, the requests are on a caseby-case basis, often leading to a negotiation depending on the requested objects. Recently, the MOV shifted their collections mandate to focus on the city of Vancouver and host Nations, so they are actively returning belongings to First Nations whose territories are in other parts of British Columbia. The Museum initiated the rematriation of over 60 Tŝilhqot’in belongings to the Tŝilhqot’in National Government. The belongings were retrieved from the MOV by a delegation of youth and Elders in February 2024.

Sacred woven baskets are known as Qatŝ’ay for the Tŝilhqot’in Peoples of British Columbia. Woven during a time when the Tŝilhqot’in lived in full harmony with their land and language, the baskets embody the craftsmanship, stories, and lifeways of their ancestors. Tŝilhqot’in territory spans the Chilcotin Plateau, west of the Fraser River and east of the Coast Mountains in British Columbia. The Nation consists of six communities that unite as one Nation, and includes forests, mountains, lakes, and rivers that have sustained them for thousands of years. The rematriation of their ancestral baskets is not just a physical return; it is about restoring spirit, culture, and connection to the land.

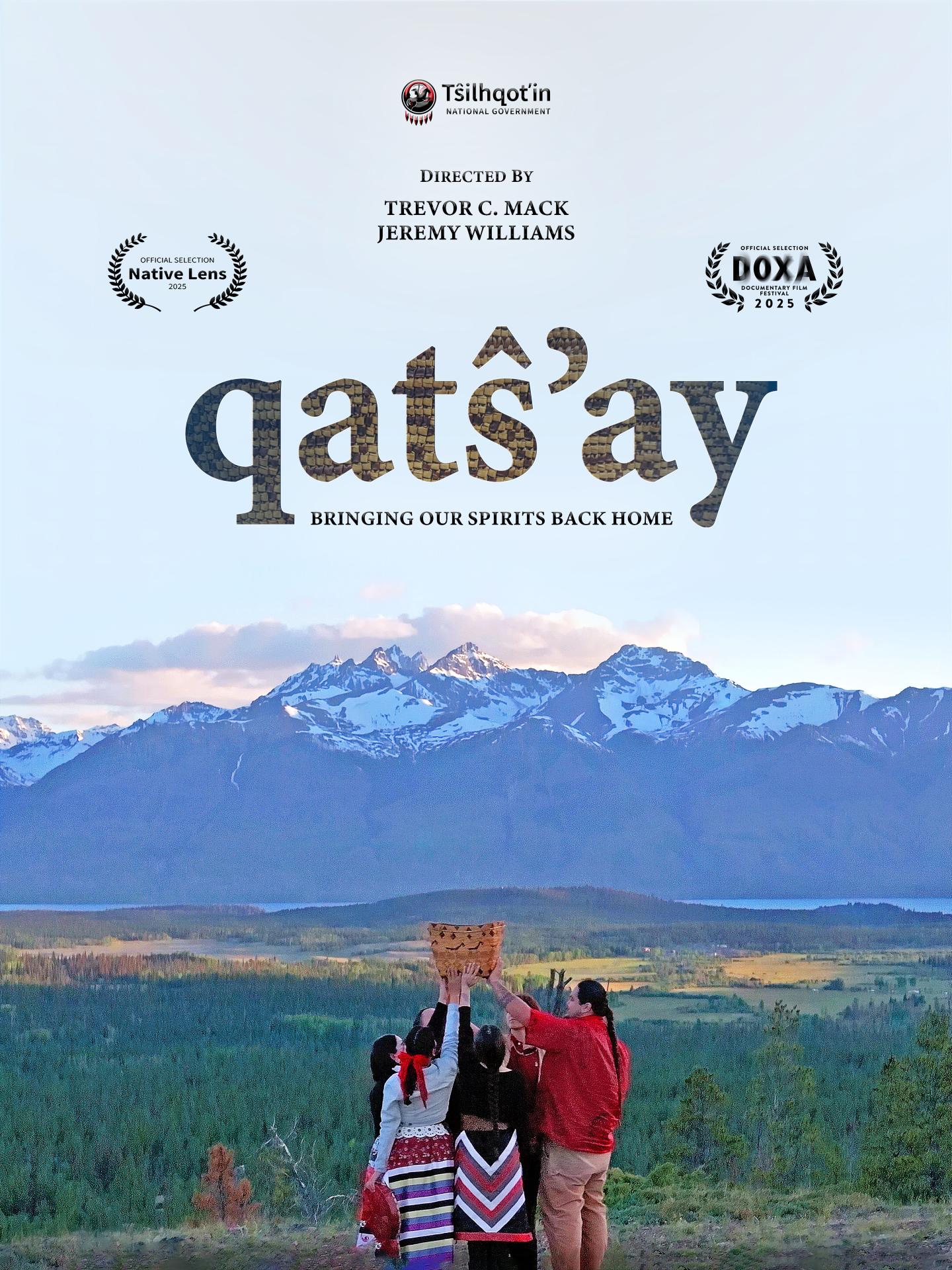

Film poster for “Qatŝ'ay: Bringing Our Spirits Back Home.”

Tŝilhqot’in youth Loretta Jeff-Combs, Peyal Laceese, and Dakota Diablo, along with Chantu and Sierra William, attended the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in April to share their efforts to reclaim these sacred woven baskets and to speak about their personal and spiritual motivations for retrieving them from museums to private collectors worldwide. The film, “Qatŝ̂’ay: Bringing Our Spirits Back Home,” directed by Trevor Mack and Jeremy Williams, showcases the journey of the rematriation process in collaboration with the Museum of Vancouver. The film, which premiered in 2025 and was presented as a side event at the Forum, will be a central feature of the Tŝilhqot’in rematriation exhibit, “Nexwenen Nataghelʔilh,” that is part of the larger exhibition, “The Work of Repair: Redress & Repatriation at the Museum of Vancouver,” opening this June.

Jeff-Combs is a leader, mother, and advocate for Indigenous youth leadership in decision-making spaces, who, alongside other youth and community leaders, has been at the heart of a growing movement to reclaim sacred baskets held for decades in museums and private collections. "I am Tŝilhqot’in, meaning 'where the rivers meet.' I'm from Tlesqox First Nations, which translates to ‘Mud Creek’,” she says. "I'm also an elected women's council representative for my community of Tlesqox. For me, this journey almost felt like a calling. My partner (Laceese) and I were walking in downtown Victoria with his late ?etsu [grandmother], who had dementia, but in that moment she was fully there, she looked at the basket and started talking about it being a Tŝilhqot’in basket. And we got to go [inside the private collection], where we got to experience this also with our daughter. It was like this was a time we needed to start bringing back these baskets, whether it be from museums or private collectors."

Loretta Jeff-Combs with daughter Nildziyenhiyah Laceese at the Museum of Vancouver. Photo by Tŝilhqot’in National Government.

Diablo is a Tŝilhqot’in youth ambassador for drug use awareness and advocates to hold the colonial government accountable for the drug crisis in his community. “The first thing that motivated me was seeing our artifacts in these museums, in these dark places, and feeling their spirit. They’re trapped in these foreign lands all across the country. It awakened something in me . . .to try and get those things back into our territory so they may thrive again,” he says.

Laceese is a Tŝilhqot’in cultural ambassador who holds spaces for healing through singing and drumming. “For myself, it was growing up hearing stories and teachings [about] who we used to be as people. Those were the people who were truly Tŝilhqot’in before European contact, and those people were in harmony and true to them- selves and spoke our language. They wove these baskets during these times. These baskets were even a legend within our own Nation, and that is what drew me . . . not only to see them, but to bring back our traditions, our cultures, our language, through these baskets, through these different items that are outside of Tŝilhqot’in throughout the world,” he says.

Bringing the baskets back is a long process that involves more than just logistics; it demands diplomacy, research, cultural knowledge, and heart. “We had to build relationships with museums, with governments, with other Indigenous Nations, and in turn, help others on the same path,” Laceese says. The most impactful thing for the youth has been the stories from the baskets, as Elders started remembering legends, names, and teachings they hadn’t heard before. Jeff-Combs recalls, “We brought our daughter. Some of the Elders brought their granddaughters. And when we went home, all of our children in our extended family were asking questions: Did we pick berries with this? Did we collect medicine with this? Can I go up the mountain and use it for medicine?”

Tŝilhqot'in youth reintroducing a selection of ancestral qatŝ'ay (baskets) to Tŝilhqot'in territory: Sierra William, Loretta Jeff-Combs, Jaemyn Baldwin, Peyal Laceese, Dakota Diablo, Chantu William, Gerald Hance. Photo by Trevor Mack.

The Tŝilhqot’in delegation to the Permanent Forum also visited ancestral belongings at several museums in New York City, while the Tŝilhqot’in National government continues to search for belongings held in museums and private collections. “We started digging, researching, and reaching out. Eventually, we became the main ones in the forefront of getting our baskets back,” says Jeff-Combs.

In the future, the Tŝilhqot’in are determined to build their own spaces to house and honor their culture and sacred items. Other members of the Nation are looking into creating their own museums back home, and ultimately, they want to have a space for their belongings in each of their six communities that would reflect the teachings and practices of that place. “There are also plans for contemporary work like baby baskets, beadwork, and dip nets that reflect our culture as it lives today. These, too, can be part of museum displays, to show we are not frozen in time. We are living, growing, and creating,” says Jeff-Combs.

While relationships with some museums have been positive, Laceese attributes the Museum of Vancouver’s rematriation of the 60 belongings to happening “because we built a strong relationship with them,” noting that the interaction with private collectors has not been as generous. “They see the value as a dollar sign. What might have been $1,000 suddenly becomes $30,000 or $50,000 when they find out we’re trying to rematriate. Some of our items are being held hostage, but we do what we can. We go to auctions. We even check thrift stores. And when we can, we buy them back,” says Laceese. “Relationship is everything—with museums, with other Indigenous Peoples, with the holders of our artifacts. That’s why we’re here. That’s why we share. To build those relationships, so we can bring our ancestors home,” adds Diablo.

Top photo: Contemporary Tŝilhqot'in artists inspired by the designs of their ancestors. L-R: Sierra William, Loretta Jeff-Combs, Chantu William. Photo by Jeremy Williams, River Voices Productions.