By Edson Krenak (Krenak, CS Staff)

After four years of frequent visits to Sigma Lithium's site in the Jequitinhonha Valley in Brazil, the situation at the tailings facility has become very concerning, prompting the Minas Gerais public prosecutor to file a public civil lawsuit against Sigma Lithium.

The Indigenous and Quilombola communities in the Jeqtuinhonha Valley face a violent cartography in a context of severe climate events and inadequate state protection. From the source of the Jequitinhonha River to its mouth, the Pataxo, Arana, Pankararau Indigenous Peoples, Quilombola, and traditional communities live in constant threat of lithium extraction without consultation, proper impact assessment, and landscape transformation, which has a substantial environmental impact.

Since 2021, communities in this region have been reporting systematic concerns regarding extraction operations, environmental degradation, and health impacts. These concerns have been documented through community monitoring, health surveys, and environmental data collected over multiple years on the ground by people living in these territories.

During COP30 in Brazil in November 2025, Cultural Survival released an Advocacy Brief outlining key concerns related to Brazil's green policies and the extraction of Lithium in the Jequitinhonha Valley. The Brief documented the context and risks facing Indigenous and Quilombola communities at that time. Subsequent developments, including a Public Civil Lawsuit (ACP) filed by the Minas Gerais Public Prosecutor's Office, have provided additional institutional documentation of these concerns.

Documented Discrepancies: Sigma Lithium's Grota do Cirila Project

Sigma Lithium's Grota do Cirila project has been widely presented in corporate communications, regulatory filings, investor presentations, and climate forums as a model of environmentally responsible lithium mining. This narrative of zero tailings and green mining is grounded in the company's Relatorio de Impacto Ambiental (RIMA) and reinforced in communications with regulators, investors, public financiers, and even in forums such as climate conferences.

However, after years of site visits and community engagement, significant discrepancies have been identified between what the company has said regarding environmental and social management and what's actually documented on the ground. This year, in partnership with the SIRGE Coalition and Earthworks, Cultural Survival conducted a technical visit to assess the tailings facilities, demonstrating not only the perspectives of the communities but also the perspectives of the companies involved. Discrepancies were identified between corporate representations and community conditions.

A preliminary assessment and independent technical analysis were conducted by an external geotechnical expert in November 2025. After consulting with the communities, we presented the findings to the Minas Gerais Public Prosecutor's Office. The analysis, undertaken by a specialist with extensive international experience in mining waste, hydrology, and tailings risk assessment, identified a series of structural safety concerns related to waste management practices at the operation. These findings, which engage with broader industry debates on tailings and waste governance, will be examined in greater detail in a subsequent article.

The Minas Gerais Public Prosecutor's Investigation

The filing of a Public Civil Lawsuit, known as an Ação Civil Pública, by the Minas Gerais Public Prosecutor's Office represents something significant because it's an institutional validation of what communities have been saying. This lawsuit document, numbered 04.160.034.0123.72020.24-64, is grounded in extensive empirical evidence gathered over the years. What makes this so significant is the scope of their investigation. They conducted multi-year field investigations from 2021 to 2025, reviewing technical reports and structural assessments. They looked at community health surveys and documented the impacts through systematic data collection. They analyzed environmental monitoring data collected from local communities and universities, and conducted statistical and geographical analyses to understand the correlations between the impacts and proximity to mining structures. The MPMG's findings indicate systematic environmental and social harm that requires immediate remedial action and independent oversight. This is not speculation or commentary. This is a state institution, having reached these conclusions after years of investigation. The amount of damages sought by the Public Prosecutor's Office is 150 million reais, which equates to approximately $30 million USD, exclusive of court fees, filing charges, and other legal expenses.

What Did the Public Civil Lawsuit Find?

Cultural Survival had access to the document (MPMG n.o 04.160.034.0123.72020.24-64 - MPE) (see image above), which presents extensive empirical evidence that materially complicates SIGMA`S narrative:

- Chronic air pollution and systematic health impacts:

- 76% of the surveyed households in local communities, Indigenous communities, and Quilombola communities reported the systematic presence of mining dust inside their homes, not as an occasional nuisance, but as a continuous exposure requiring regular medical emergency care for the elderly.

- Environmental monitoring data show recurrent exceedances of legal limits for PM2.5 and PM10 pollutants associated with respiratory and cardiovascular diseases

The right to health and an ecologically balanced environment is not for Indigenous communities only, but for all, children, the elderly, civil society, and even the mining workers.

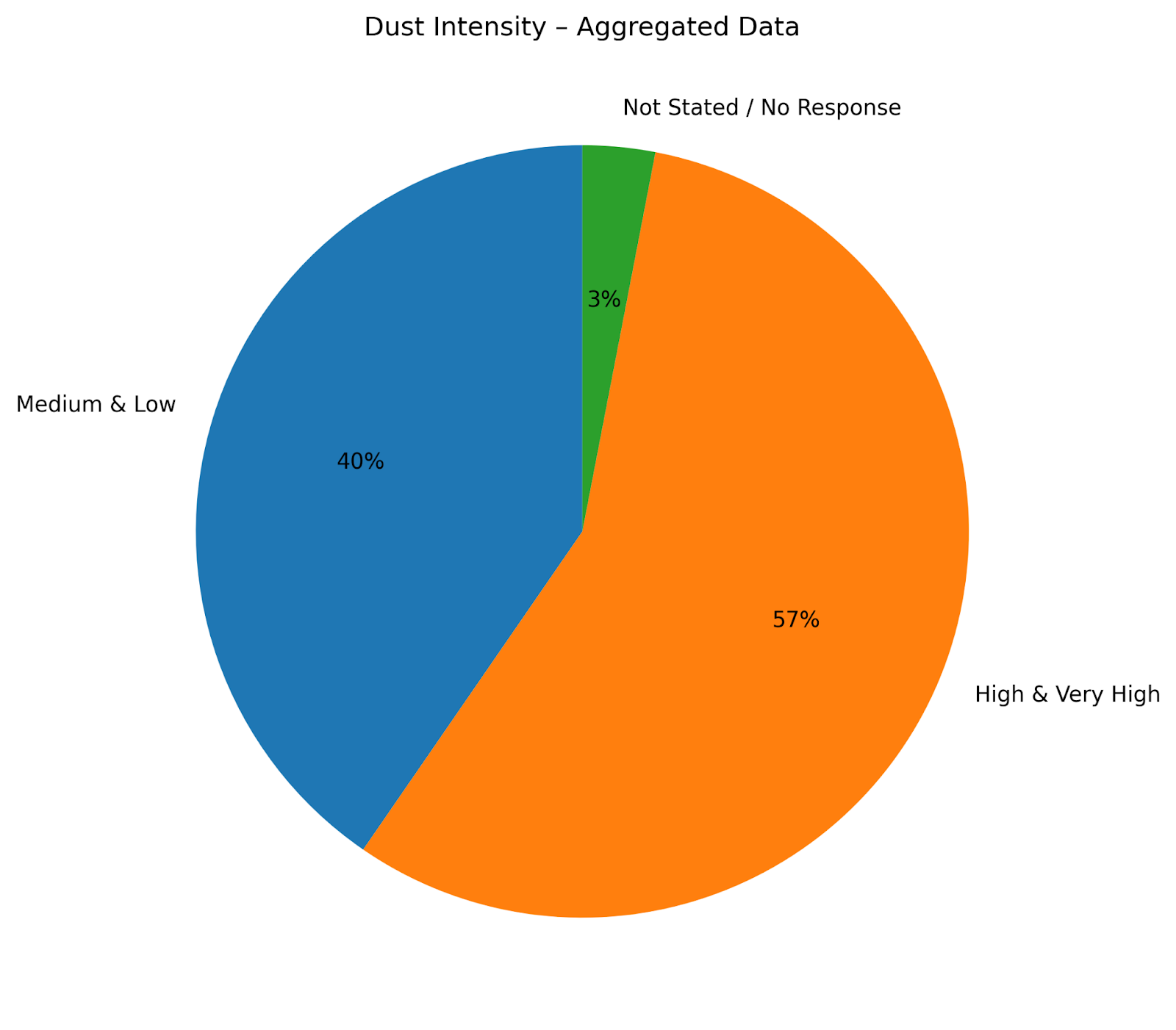

Dust Intensity (Aggregated Data). Source: Technical Report CAOMA/CAO-CIMOS / Minas Gerais Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPMG).

- Noise pollution and sleep deprivation

- 100 % of the residents of the Posto Dantas, Ponte do Piaui, and Santa Lucia reported disturbance from industrial noise.

- 70% classified the noise as high or very high, with nighttime exceedances reaching 87% above permitted limits in some monitoring periods

This is usually linked to stress, sleep disorders, and degradation of physical and mental well being.

- Vibrations, structural damage, and fear

- 89% of residents were affected by vibrations from blasting.

- 50% of inspected houses showed cracks that appeared to worsen after mining operations began

This brings a constant fear among people and animals, fear of collapse or destruction, bringing psychological harm to them.

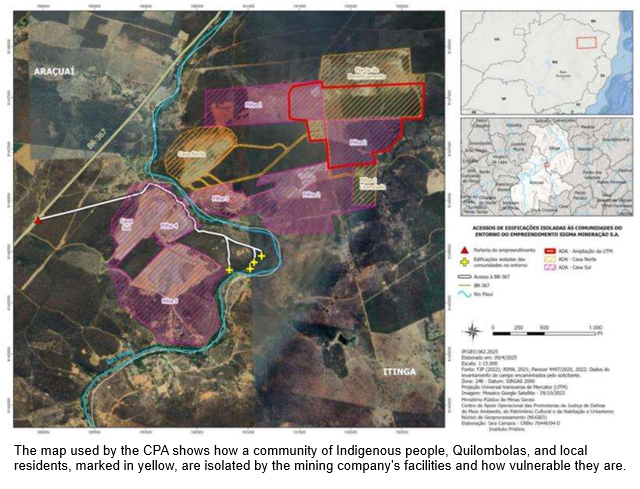

- Extreme proximity and social isolation

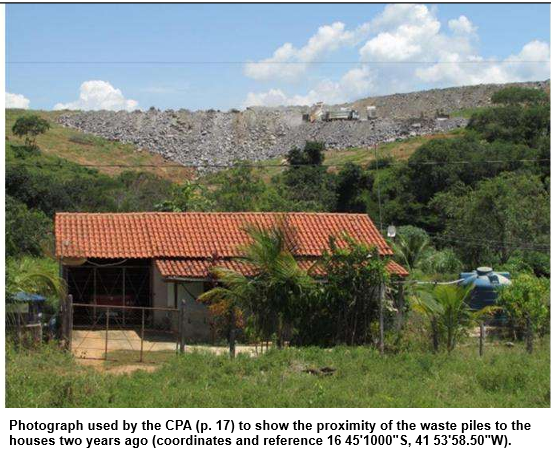

- A significant number of homes and even a children's school are located within 250 to 500 meters of mining structures, with some residents as close as 8 meters. The school (the pictures) is just 500 meters away from the piles, which, according to experts, pose a considerable concern due to their failure to adhere to any industrial standard.

Rock, waste, and tailing facility/piles without a dam or embankments for safety show in the back of the image. A school and community houses in the front plane. Photo by Edson Krenak.

- Casual Nexus and regulatory concern

- The MPMG's multidisciplinary analysis identifies statistical and geographical correlations between impacts (dust, noise, vibration, harm to fauna and flora) and proximity to mining structures.

- The lawsuit explicitly questions the adequacy of company self-monitoring, underscoring the absence of independent auditing for critical parameters such as vibration impacts

School facade and piles behind it. Photo by Edson Krenak.

School facade and piles behind it. Photo by Edson Krenak.

Sigma claims that it has no tailings (see website image below). Still, from the perspective of the Global Tailings Management Institute (GTMI) and the Global Industry Standard in Tailings Management (GISTM), the documented dust exposure constituted a material tailings-related risk, regardless of how the operator classified the waste. Under the GISTM, tailings are understood not narrowly as a specific storage technology, but as any mining waste whose management may pose a hazard, defined as “any substance, human activity, condition or other agent that may cause harm, loss of life, injury, health impacts, loss of integrity of natural or built structures, property damage, loss of livelihoods or services, social and economic disruption, or environmental damage (https://www.tailingsinsights.com/gistm).”

The MPMG documented that in this context, 56% of households experience high or very high dust intensity, with widespread chronic exposure, indicating that the material stored and handled on site, even without a dam or containment structure, functions as tailings in both risk and impact terms - indicators that are essential for environmental, social, and cultural assessments.

Such conditions are incompatible with the GISTM's core objective of “zero harm to people and the environment." They would, under the standard and the Minas Gerais and Brazilian regulations, require immediate corrective action, an independent review, and reassessment of operational controls, particularly given the proximity of communities and sensitive receptors, as well as the cultural impacts on Indigenous and Quilombola communities.

Due Diligence Gaps: BNDS Financing Decision

In November 2025, during COP30, we had the opportunity to present our findings to representatives of the Brazilian Development Bank, which had approved financing for Sigma Lithium from its Climate Fund. When Cultural Survival spoke with them, they were not aware of the situation we were describing and the level of impacts that communities are experiencing.

After the BNDS approved the financing, a comprehensive field investigation by the Minas Gerais Public Prosecutor's Office documented something important. There were material discrepancies between what the company projected as impacts and what communities are actually experiencing. The projected impacts differed significantly from what was documented once people actually investigated.

This suggests that the due diligence procedures employed were insufficient to capture the scope and severity of environmental and social impacts affecting vulnerable Indigenous and Quilombola communities. The gap between what was assumed and what's real is significant.

Also, according to available records, this fund has never provided financing for climate adaptation projects that actually benefit local Indigenous or Quilombola communities in the Jequitinhonha Valley. The climate fund is financing extraction activities that harm these communities, but not financing adaptation for the communities being affected.

According to the Brazilian Institute of Consumer Rights, documented discrepancies exist between what BNDS commits to in its policies and its actual actions. They point to limited transparency and public accessibility of due diligence documentation. Some of the critical environmental assessment documents are published only in English, which limits access for communities and local organizations that work in Portuguese. And they note that BNDS has approved projects despite documented community complaints regarding environmental degradation, health impacts, and human rights concerns. So this isn't just about Sigma. It's a pattern.

This situation does not imply impropriety, but it does suggest a serious structural gap in due diligence, where persuasive ESG narrative and formal compliance documentation were not sufficiently tested against on-the-ground conditions in a historically vulnerable territory such as the Jequitinhonha Valley. These problems could have been avoided with proper Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

Overdue Diligence and the Narrative that Ignored Basic Rights

The Prosecution Office's conclusion, based on independent assessments and high-level technical analysis, confirmed not only our own studies but also what we have heard and amplified several times from the affected communities: Sigma's practices indicate violations of fundamental rights resulting from operational malpractice and insufficient due diligence.

According to the ACP argument, the company systematically promoted a narrative of "sustainable mining" and "green technology" that enchanted even the powerful BNDS and other investors. The "practice of greenwashing (misleading green advertising) constitutes a perverse form of environmental disinformation that facilitates the attraction of investments and the granting of environmental licenses at the expense of “local communities, indigenous people, and quilombolas" (ACP).

It contradicted the documented socio-environmental harms, characterizing a pattern of greenwashing that facilitates investment and licensing while externalizing costs to local populations, transforming their territories into sacrifice zones. Several independent academic analyses further demonstrate that SIGMA deliberately opted for an open-pit mining method with significantly higher land consumption and waste generation, despite the existence of less impactful underground alternatives in the same region (see CBL, the longest lithium mining company in the area).

Taken together, the ACP`s evidence substantiates violations of multiple fundamental rights, including:

1. rights to an ecologically healthy and balanced environment,

2. right to health

3. right to information

4. right to housing

3. right to information

5. right to peace and well-being

6. right to freedom of movement

7. right to leisure and safety

The Jequitinhonha Valley case demonstrates that extraction can proceed under a green mining and sustainability narrative while causing documented systematic harm to vulnerable Indigenous and Quilombola communities. Institutional due diligence gaps, particularly the absence of on-site verification, independent technical review, and meaningful community consultation, allow this contradiction to persist.

The Minas Gerais Public Prosecutor's investigation provides validation of community concerns. It demonstrates that systematic harm was preventable through the implementation of rights-based approaches centered on Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

As Brazil positions itself as a climate leader through COP30 and green mining initiatives, the lived experience of affected Indigenous and Quilombola communities in the Jequitinhonha Valley must be at the center of those initiatives. “Green mining” that violates Indigenous rights, causes documented health harms, and proceeds without genuine community consent is not green, not even legal. It's colonial and harmful extractivism with rich public relations.

Many communities around the world face the same climate impacts as in the Jequitinhonha Valley: heat, drought, and floods. Meaningful climate action requires centering Indigenous peoples as decision-makers and rights-holders, not as consultation checkboxes in processes designed to proceed regardless of community will. The findings of the Minas Gerais Public Prosecutor's Office provide a roadmap for how institutions can verify corporate claims against the reality of their territories and ensure that climate finance genuinely contributes to both climate mitigation and justice for vulnerable communities.

The issues appear to have escalated with the senior executive of SIGMA`s participation in COP30, where language is perceived as racist and discriminatory by traditional communities and civil society in Aracuai and Itinga, where the company operates its projects. Her remarks were seen as so dismissive and condescending that they prompted dozens of organizations to plan a public protest and march against her. Several social media platforms have reported a mobilization of 68 organizations repudiating any recognition of her person.

Our investigation reveals Sigma is not an isolated actor. Despite two months of outreach, BNDS has not responded to our requests for information on why its Climate Fund is financing a company with significant operational and social failures, nor has it clarified its ESG policies. The bank`s ombudsman has also remained silent, as shown in the communication protocol (image below).

According to the available documents, Sigma Lithium made the required risk disclosures to BNDES and investors as mandated by law. However, the key issue highlighted here, by the prosecutor`s investigation and Indigenous and local communities, is that the company`s sustainable mining narrative acted as a form of "green washing", which misled stakeholders by creating a discrepancy between its advertised practices and the documented socio-environmental harm on the ground.

The question now is how investors, including the BNDES, conducted their due diligence and approved financing for SIGMA`s projects without verifying the absence of meaningful Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), while continuing to fund operations linked to documented, systematic human rights violations against Indigenous, Quilombolas, and local communities?

Major financial institutions, including public banks like the BNDS, appear committed to environmental and social governance (ESG) principles, yet they continue to finance projects that a public prosecutor has identified as violating fundamental rights. This implication is that the financial sector`s own safeguards failed, treating community consent as a consultation checkbox, verified by armchair observation, rather than a non-negotiable rights-based requirement, thereby enabling the "green washing. The financiers are, thus, complicit in the harm by providing capital that allowed the violation to persist.

Top photo by Rebeca Binda.

Read: Jequitinhoonha Valley: the violent cartography of Lithium - Part II