By Esénia Bañuelos (CS Intern)

When prompted to consider outstanding individuals to honor for International Mother Language Day, I immediately thought of my first example of Indigenous-led language education: my own professor, Felipe H. Lopez, from whom I learned in his conversational San Lucas Quiaviní language course at Haverford College.

Lopez, a Seton Hall University professor, literary artist, and language activist, was born in the pueblo and municipality of San Lucas Quiaviní in the east of the central valley in Oaxaca, southwestern México. This pueblo, along with its neighbors, is a testament to the vibrant and ever-growing Zapotec ethnolinguistic communities; in Oaxaca alone there are over 40 distinct languages, and within the Valley there are at least 12. Today, Dizhsa is spoken by the majority of the adults in San Lucas Quiaviní, though the pueblo’s younger community has been shifting towards integration into the Mexican public school system, and thus Spanish monolingualism.

Lopez spent his earliest years in the pueblo as a native speaker of Dizhsa in a time where traditional public schooling was led by individuals who identified as Mestizo, or descendants of Spanish colonizers and Mesoamerican Indigenous Peoples, attempted to assimilate Indigenous youth into the Spanish-speaking, non-Indigenous cultural program. In his third year of elementary education in the Mexican public school system, Lopez’s father enrolled him in a boarding school for Indigenous youth. The subsequent years in which he experienced anti-Indigenism in México deeply impacted his comfortability in speaking Dizhsa. “When you’re nine or 10 years old, you just want to be included,” Lopez laments. “I rejected so much of what I was.”

As a teenager, Lopez immigrated to the United States with a predominantly Dizhsa linguistic background and minimal comfortability speaking Spanish. Los Angeles, California, was then, and is still now, a transbordering home for members of the Zapotec diaspora, including those who were born in San Lucas Quiaviní. However, the linguistic repertoire of the diaspora in California, as in México, was rapidly evolving. “I noticed that [Zapotec] parents were teaching their children Spanish, not Zapotec. I noticed that my language was going to disappear some day. It made me want a record of my language,” Lopez says, a desire that would be the impetus for his decades-long work in Dizhsa language reclamation.

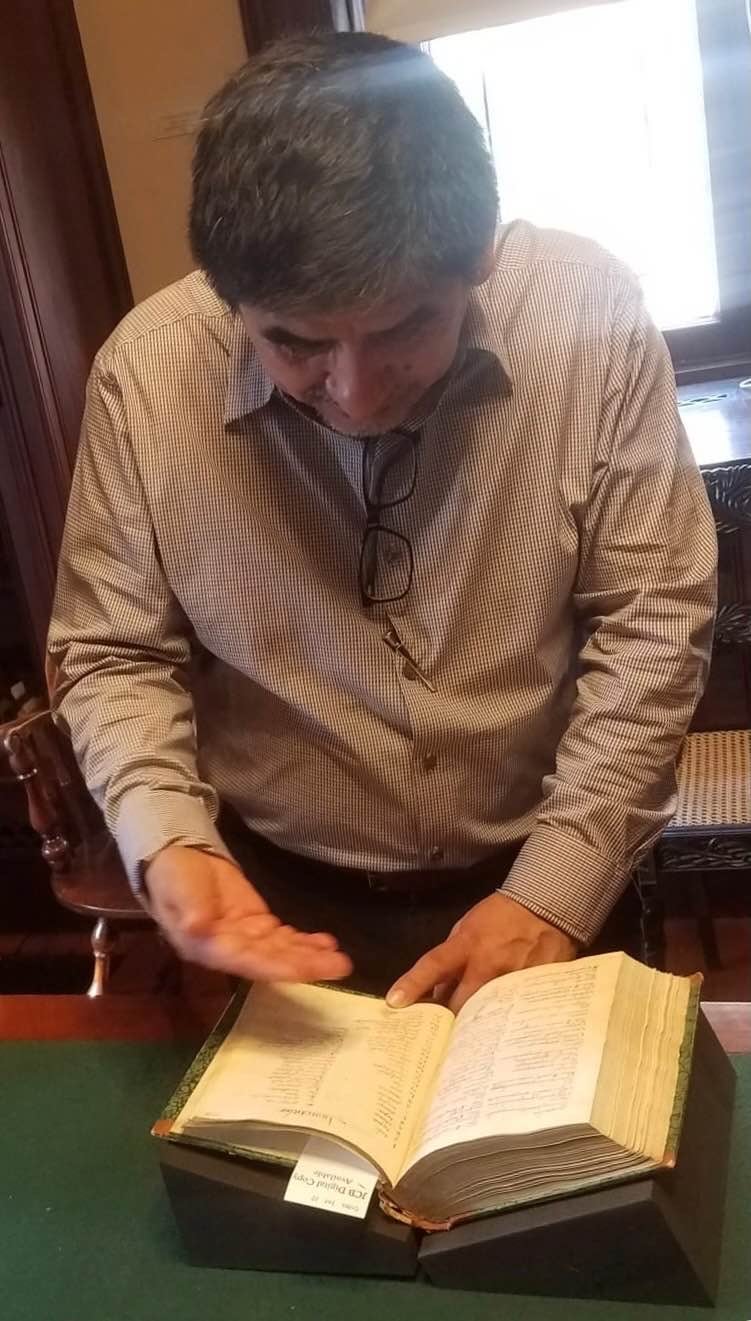

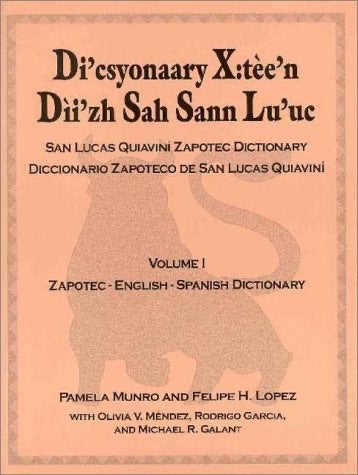

It would be at UCLA where Lopez grouped with fellow graduate students in the field of Mesoamerican Indigenous linguistics, along with Drs. Michael Gallant, Pamela Munro, and Brook Danielle Lillehaugen, to create the first volume of the Zapotec-led community language dictionary in Spanish and English: Di'csyonaary X:tèe'n Dìi'zh Sah Sann Lu'uc. This feat was not without significant challenge, as the process required creating an orthography within the Latin alphabet. Lopez stresses the importance of community involvement in the co-creation of the Dizhsa dictionary, reflecting on the moment he presented the first volume to the students of a local preschool in San Lucas Quiaviní. “There were many questions,” he recalls. “‘How do you write this?’ ‘How do you pronounce this?’ If you look at the entries, they are so complex.”

Through intensive community collaboration and dialogue, the second volume of the dictionary proved more accessible to members of the community and led to its installation into a language course for the diaspora at the University of California, San Diego in 2005, as well as at el Universidad del Pueblo, which serves several Valley Zapotec communities.

The formalization of Dizhsa pedagogy in contemporary México and the United States is not without significant challenges. Both nation-states have embedded anti-Indigeneity into their very constitutions through the diminutive nature of referring to Indigenous languages as “dialects” to outlawing or otherwise prohibiting the use and teaching of Indigenous languages in institutions, and especially by Indigenous educators. This practice is not a thing of the past—it is present in our colonial prescriptions for what comprises legitimate language. “Many [Zapotec] parents ask me, ‘Why Dizhsa? Why not a language with use, like English?’” This form of anti-Indigenous racism pervades and aims to dismantle Indigenous language reclamation efforts, but it has never deterred Lopez from advancing reclamation efforts for Dizhsa at every level of American and Mexican educational institutions. “All I cared about was, how do I help the kids? My aim was to give knowledge to the community. Language, in México, is an economic means. Zapotec teachers have had to ‘sell’ the usefulness of the language to their parents. [We] had to convince [them] by reminding them that if their children go into agriculture, medicine, or law, they can reach more people by knowing an Indigenous language,” he says.

Within his first 10 years of teaching Dizhsa, Lopez joined the Zapotec Advisory Board of The Ticha Project, which emerged as a nonprofit educational organization marked by a Zapotec agenda (Zapotec community priorities as heading guidelines) and Indigenous councilship dedicated to advancing and making visible and freely accessible multiple forms of Valley Zapotec language resources. The organization’s mission is to “document and promote Zapotec languages and knowledge through workshops, events, and online resources provided to the public at no cost.” Numerous, though not exhaustive, examples of their work include a fully digitized body of colonial manuscripts from Zapotec writers, teaching modules dedicated to Zapotec history and linguistics for English- and Spanish-speaking teachers to incorporate into their classrooms, and the first decolonial dictionary created with Zapotec communities and Haverford College students of Lopez, Lillehaugen, and Dr. George Aaron Broadwell in the Fall of 2024.

Lopez’s course, of which I am a proud alum, was a progression of one of his remarkable endeavors in Dizhsa language education: Cali Chiu. An open-source and publicly accessible textbook named for the colloquial Dizhsa greeting most closely translated in English as “Where are you going?”, Cali Chiu was created and continues to be developed in collaboration with two Dizhsa sisters and educators living in the pueblo, Ana and Geraldina López-Curiel, along with linguists Lillian Leibovich, Lillehaugen, Munro, and Brynn Paul. It is resistance in an open educational resource (OER). The entire book, available in both Spanish and English, contains natural example sentences found in Dizhsa, pronunciation by community speakers captured in audio recordings and videos, and a thorough explanation of Zapotec community epistemologies alongside introductory and accessible passages through syntax, phonology, semantics, and morphology for any member of the diaspora, or any person wanting to learn Dizhsa, regardless of their age and linguistic background.

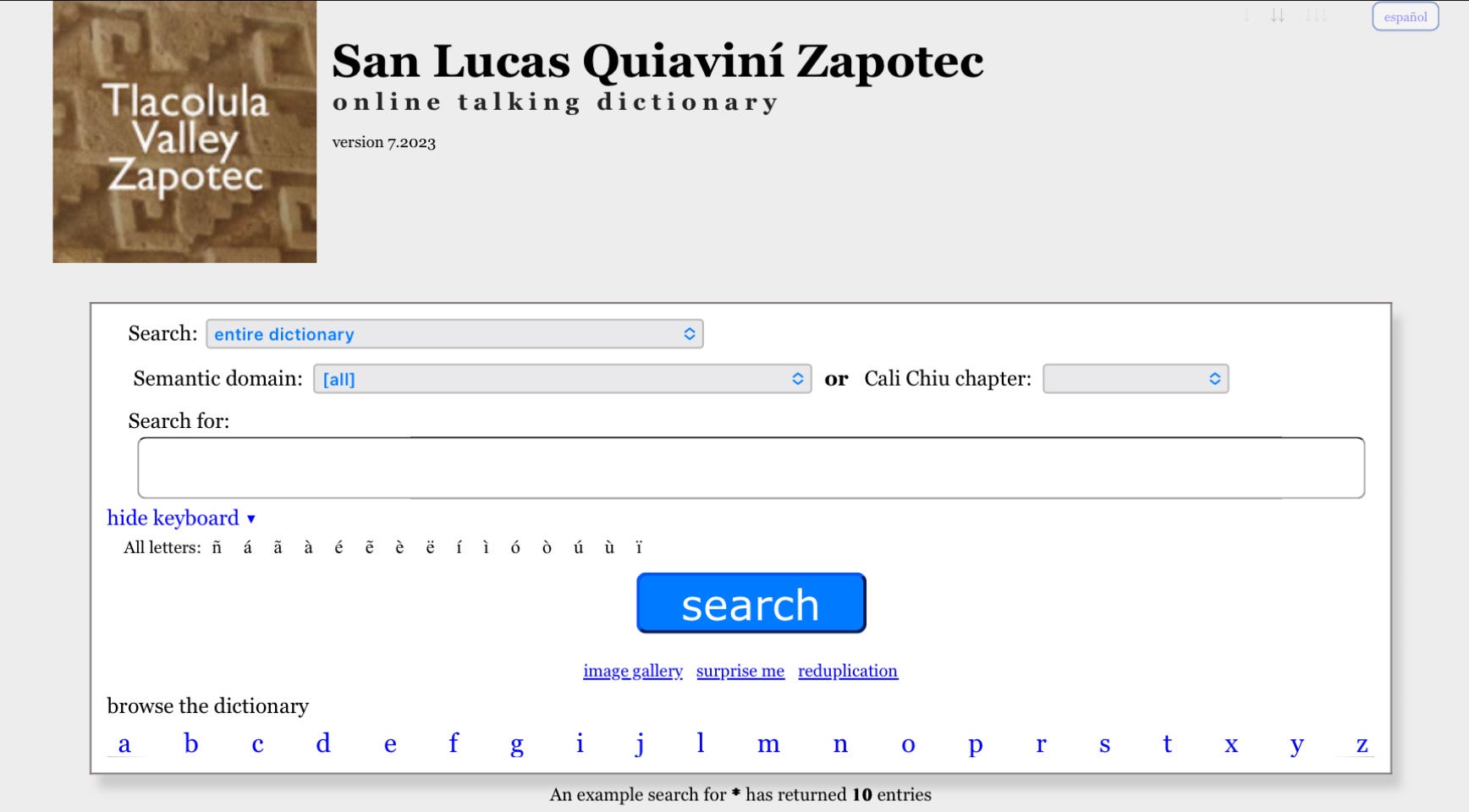

Cali Chiu is complemented by the Dizhsa talking dictionary Lopez has created and continues to build upon in partnership with the López-Curiel sisters. Replete with accessible audio recordings of individual words, example sentences, and definitions decided by Dizhsa speakers, the dictionary is a de-facto act of resistance in the continued community creation and negotiation of Dizhsa. “A talking dictionary is an online resource that allows Zapotec and non-Zapotec people to learn Dizhsa,” Lopez says. “Making it available online makes it so that it is not limited to one community in Oaxaca, but the children in the diaspora—first and second generation Zapotecs—can learn the language of their parents.” He notes that the Dizhsa talking dictionary has already been impactful across the diaspora, often consulted by people looking for baby names or ways to say ‘I love you.’ Some users have even connected with him personally: “People will find me through social media and ask me questions like, ‘How do you write this?’ ‘How do you say this?’”

The incredible efforts being placed into the dictionary are transbordering. The Zapotec Language Institute is a Pennsylvania-based nonprofit educational organization headed by Lopez with the stated goal of “financially supporting volunteer Valley Zapotec language educators teaching their language free of charge and organizing public educational programing to facilitate Valley Zapotec language education.” It has included a strong network of local volunteers from Bryn Mawr and Haverford College who collaborate with Zapotec community members in the design of pedagogical materials at the primary, secondary, and post-secondary levels, transcribing and translating manuscripts written in Ticha zaa and supporting multiple Valley Zapotec talking dictionaries and classrooms, including the Zapotec languages of Teotitlán del Valle and San Jeronimó Tlacochahuaya.

The work being done is intersectional and dynamic, with the involvement of community Elders in the process of documenting Dizhsa. “When I started working with the manuscripts, I began to see some of the words that my grandmother used. Counting is one that stands out to me. Even working with the dictionary, we didn’t have [loanwords] for 60—we used ‘sesent.’ I thought, ‘Wow! My grandma used to say that!’ To confirm, I went to the Elders of the community and I would ask, ‘Hey! Is this a word?’ Sometimes they wouldn’t be sure, and sometimes they would,” Lopez says, reflecting on the major development in accessing historical Ticha zaa texts. “‘Xon,’ for example, still exists in my town through the eldest generation,” he says.

Lopez’s impact in the documentation and reclamation of Dizhsa is interdisciplinary and groundbreaking in the international creation of contemporary Indigenous literary arts. Dizhsa is not a common language of the literary arts of the Americas, so Lopez has dedicated his creative endeavors to producing award-winning poems and short stories in Dizhsa, some of which can be found in Cali Chiu. In his poem, “Guepy,” (“Origin”), Lopez touches San Lucas Quiaviní: “Cali bsani xquepyu? / Ricyi na lazhu.” (Where did you leave your umbilical cord? / That is where your pueblo is.) In his essay covering the translation of his art into Spanish and English from Dizhsa for ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America, he writes, “Writing in Dizhsa, for me, is an initiative (of) self-representation, of both my culture and my own Zapotec identity…. My priority in translating is to convey the intimacy of my thoughts to the reader in both English and Spanish in a way that reflects the Zapotec perspective as closely as possible, without privileging having to ‘write beautifully’ in English or Spanish.”

The language endeavor that Lopez has undertaken in reclaiming and leading Dizhsa education is unsurpassed in its impact, whether it be in verse or lexicography, in the classroom in Pennsylvania, California, or Oaxaca. Dizhsa language education, Zapotec language education—Indigenous language education—is leading to a revolution and rapid growth in the sustained use and continued documentation of the language. I feel an immense privilege to call myself an alum of the conversational San Lucas Quiaviní course, and for having the opportunity to engage in dialogue with the incredible lexicographer, author, linguist, and educator, Felipe H. Lopez, this International Mother Language Day.