By Akash Poyam (Gond/Koitur, CS Fellow)

During the monsoon, driving along the roads leading to Chaura village from the Surguja district headquarters town of Ambikapur, the view is breathtaking: lush green forests of saal, mahua, and tendu trees stand alongside green paddies, corn, and sugarcane fields. Closer to Chaura, the landscape suddenly changes. Trucks line up one after another on both sides of the dusty road. The coal dust makes visibility so low that vehicles have to turn on their lights, while people have to cover their faces. The buildings, the fields, and anything near the mine are coated with coal dust. The paddy fields along the roadside have black mud, a product of coal waste from a nearby dump that flows into the fields during the monsoon rains. At around 1 p.m. every day, the sound of blasting can be heard clearly from Chaura and the surrounding villages. Some houses have cracks in their walls from these blasts. The wastewater from the coal mine is dumped into the nearby water source that is used by people, animals, and for agricultural purposes.

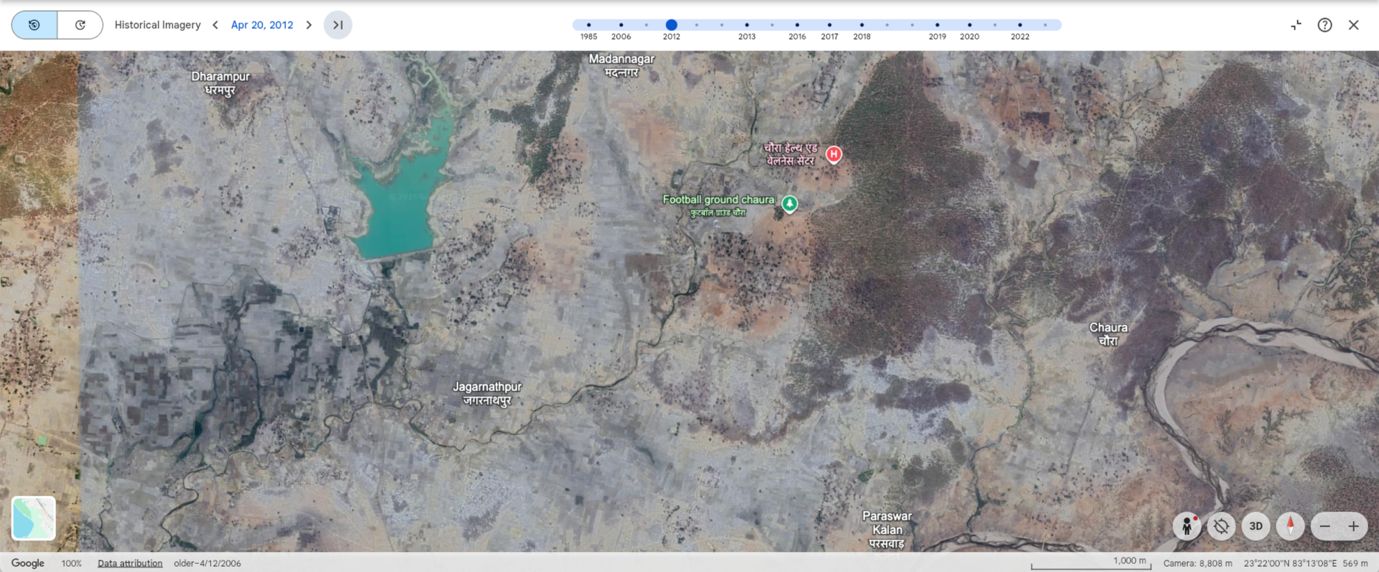

Satellite image of Mahan II and III in 2012.

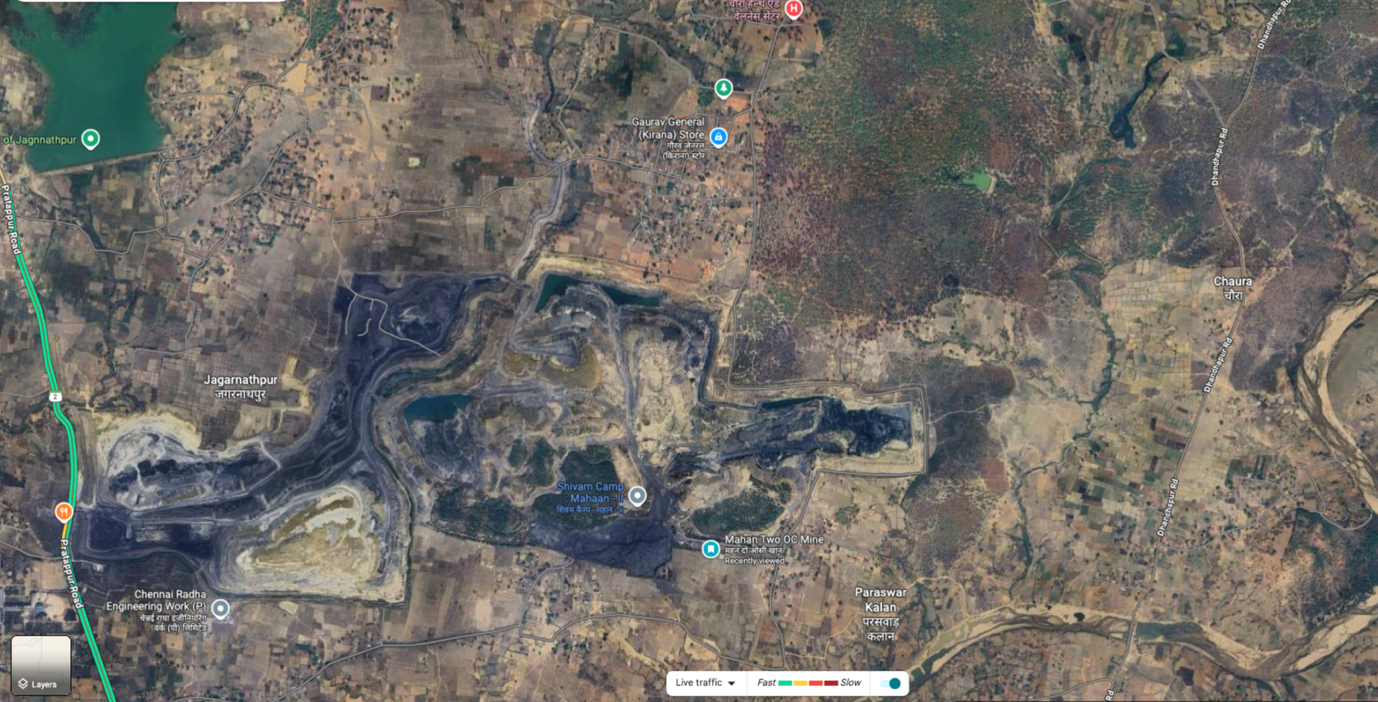

Satellite image of Mahan II and III in 2025.

The satellite imagery of the Mahan II and III coal mines shows the scale of destruction of farm and forest land in the region. The northern part of the mines contains a large lake, a clean water body, which is at risk of pollution from untreated water released from the coal mines. Over a decade, the South Eastern Coalfields Limited (SECL) mining company, a subsidiary of Coal India Limited, managed to expand its project despite community resistance. The proposed new expansion further north into the village of Madanpur will lead to continued destruction of forest, farmland, and sacred Tribal spaces.

Coal dump yard of Mahan II coal block near the paddy fields. During monsoons, the coal dump flows into the paddy fields turning the mud and soil black.

Corn and paddy fields on the way to Chaura village. Vegetation grows on top of coal dump yards.

Trucks lined up in front of Mahan II. During monsoons, the road becomes muddy with black soil, and during the dry season, the road becomes overwhelmingly filled with coal dust.

Chaura is located in the Balrampur district of north Chhattisgarh, and is one of the villages displaced by SECL’s Mahan II open-cast coal mine. The operation of Mahan II began around 2008, and is now in the third and fourth phase (Mahan III and Mahan IV) after being mined to its capacity. The three main villages affected by Mahan II are Chaura, Jagannathpur, and Madannagar. Parts of Chaura have already been displaced, and the remaining village is barely 500 meters from the coal mine. Mahan III is currently operational in Jagannathpur, while Madannagar lies within Mahan IV.

The three villages lie within the Balrampur and Surajpur districts of north Chhattisgarh. Both of these districts come under the Fifth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, which provides significant autonomy to Tribal communities over land, forests, and resources. The Constitution mandates the consent of a gram sabha (village-level body formed by Tribal and local communities) for any development projects in their region. Section 4 and 5 of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers Act 2006, also known as the Forest Rights Act, or FRA, make consent of gram sabha mandatory for any activity that affects them and the biodiversity around them. The 1996 Panchayat Act, or PESA, which confers autonomy to Tribal communities, also makes the consent of gram sabha mandatory for any land acquisition.

Districts where SECL is operating coal mines, with the main concentration in north Chhattisgarh. Mahan II lies in the northernmost Balrampur and Surajpur districts. Map sourced from an SECL document.

SECL operates 57 major coal projects in various parts of Chhattisgarh state, which has the highest Scheduled Tribe population in any state in mainland India—about 33 percent. In the 2024-25 fiscal year, SECL’s net coal production was over 167 million metric tonnes, with a gross sales value of 35,871 crore ($4.8 billion USD).

Mahan II and III

The Mahan II open-cast coal mine project officially began operating in 2008, though surveying began in the 1990s. Mahan II had an initial capacity of one million metric tonnes per year with a mining lease over an area of 275 hectares. The total output of Mahan II was projected to be 22.2 million metric tonnes. According to one environmental clearance document, a public hearing was held in 2016 for the Jangannathpur mine. The document states that the project would cover a total area of 661.169 hectares and that the total number of affected persons would be 616. The report notes that public hearings were held on February 10, 2017, in Chaura village and on March 17, 2017, in Jagannathpur village. The scanned copy of the public hearing document, written in the form of a letter on behalf of Chaura village, reads in part, “We are the villagers of Chaura...and we have all agreed to give our land to the SECL...with the opening of the mines, our future generations will benefit socially and economically. And the villagers will benefit directly or indirectly from the mines.” At least five such letters were entered into the record, purportedly written by the villagers, with the same wording, ending with their signatures. The identical letters written in favor of SECL signal that the public hearing did not follow the required process of Free, Prior and Informed Consent of the Tribal communities.

The Mahan III and IV mines are an expansion of the Mahan II mine. The Jagannathpur project is named after Jagannathpur village, has a planned life of approximately 22 years, with total mineable reserves estimated at 55.89 million metric tonnes. The mining lease area encompasses significant agricultural and forest land, requiring careful environmental management and rehabilitation planning. These mines supply thermal coal primarily to power stations, supporting India’s electricity generation capacity.

The Fake Gram Sabha and the Community’s Resistance

I first saw the Mahan II coal mine while I was visiting my grandmother’s village, which is adjacent to the ongoing project and only a few kilometers away. At the time, I met with the head of the village and was informed that the community had been resisting the coal mine. Ten years later, when I revisited these villages as part of the Cultural Survival Investigative Journalism Fellowship, everything had changed drastically. The mine, which was then only in the first stage, had now been expanded to three more phases with land acquisition and possible displacement of two more villages.

Sonsai, former sarpanch of Chaura village, who led the resistance against SECL coal mines, during an interview in his backyard.

“There was no gram sabha,” Sonsai, a former sarpanch (elected village leader), says. “The said gram sabha was fabricated through fraudulent means.” According to Sonsai, the villagers protested when the project was being expanded to Mahan IV, and as a result, a gram sabha was held for the project’s expansion. “During Mahan III, I asked people how many support the project and how many don’t…and the majority of villagers were in opposition to the project,” he says. Despite this, the Mahan III and IV expansion continued, and the voices of the villagers were ignored. “The mine was opened through force,” Sonsai says, and no constitutional due procedure was followed.

Sonsai belongs to the Gond Tribe and is one of the eldest persons in Chaura village. He was the sarpanch for 20 years, from 1978-1998, and is one of the leading voices of resistance against Mahan coal mines in the region. Sonsai was reelected in 2015 when the Mahan III proposal was underway. “From there on, things became disastrous and the mining began,” he says. “I kept resisting, but nothing happened.” When the project was expanded to Mahan III, Sonsai led the resistance again and mobilized people. “The supporters of the mine were chaar aana, and those wanting to save were barah aana.” Those who wanted to save the land and forest were in the majority, he adds. Sonsai faced a criminal charge for his resistance against mining. “The case won’t go as long as the mining is here,” he was told. Sonsai was not alone in facing police persecution; 10 other people from the village had cases filed against them for opposing SECL mines.

“For a month, people from Jagannathpur sat as watchguards to stop SECL from mining,” Sonsai recalls. “The company brought its [excavators] along with the police, and people got scared and backed away.” At this point, the majority of the people went in favor of the company. “Only a handful of us couldn’t continue the protest, so we stopped. Then Mahan III began its operations,” he says, reiterating that the mines were opened “through force.” At one point, there were regular protests from Tribal communities against the mines; however, SECL managed to get the head of the village on their side. “We felt that whatever happened with Mahan II shouldn’t happen with Mahan III. But even in Mahan III, people lost the battle,” Sonsai says. Once his tenure as sarpanch ended in 2020, SECL managed to expand the project to Mahan IV.

“During the resistance movement against SECL, there were two organized groups in Chaura and Jagannathpur consisting of affected Tribal villagers,” Sonsai says. The families with small land holdings suffered the most. “When the families with large land holdings agreed to give land to the company, the smaller and economically weaker families also got trapped.”

Paddy fields in Chaura village. Though the coal dust is not visible, its residue has settled on crops, plants, and trees.

When Sonsai was sarpanch in the 1990s, the geological survey for the Mahan project had already taken place. “I wasn’t aware that the survey was being done for the coal mine,” he says. The first proposal for Mahan II came around 2007-08, when he was not a sarpanch, under the leadership of a non-Tribal sachiv (secretary to the sarpanch), who collaborated with SECL and conducted a fake gram sabha in 2008. “After that it didn’t stop, and now we have Mahan III and IV.” Sonsai recalls that just a handful of people from Chaura and Jagannathpur village went to the district officials and demanded that their land and forest be protected, but it was already too late. “The coal mine is currently operational, but it did not begin with due process and constitutional mandates,” he says.

The first hamlet that agreed to cede land for Mahan II was dominated by people from the Oraon Tribe. “They felt the mine would give them jobs,” one of the villagers said during a group discussion. “However, they lost their homes and are now scattered across the region, not finding land to bury their dead.” Most of them moved away from their native village and now have to take shelter in Chaura village, while others managed to buy land elsewhere. Sonsai says that people had no other options.

When the expansion for Mahan III began, there was opposition from the affected villages, and a formal gram sabha was conducted. “The majority of villagers were in opposition to the Mahan III expansion, and gram sabha rejected the proposal,” Sonsai recalls. “However, SECL still managed to start mining with the help of a few people from the village itself.” In many mining areas, a clear generational gap can be seen, as was the case with Mahan coal mines. Sonsai says that the Elders in the village did not want to give the land, but the younger generations supported the project because of the lucrative offers of employment made by SECL. The company managed to divide the village into two groups, and the villagers couldn’t be united.

One of the villagers of Chaura, Sohan, remembers the beginning of the Mahan III mine. “When Mahan III began in 2013, we didn’t want to give up our land. But we got trapped in confusion, as everyone else was giving their land, so we had to give up our land,” he says. In the first phase of the mines, Mahan II, people were given compensation as low as 60,000-80,000 rupees (around $650-870 USD) per acre; however, after the implementation of the new Land Acquisition and Rehabilitation Act in 2013, the compensation amount increased 10-fold. The villagers did not receive any rehabilitation for the project, and no alternative housing was built for the displaced families.

Coal bricks collected by villagers for their personal use in Chaura village.

Like Mahan II, Sohan says that the gram sabha for Mahan III did not take place through due process. “We were tricked by SECL,” says. “What could we do?” Sohan recalls that while a gram sabha was held for Mahan III and people opposed the project, SECL still managed to continue mining in the village. His son was given a job in SECL as compensation for the loss of land, and partly because of that, he is apprehensive of sharing more details of SECL’s fraudulent practices. But, he will speak to the environmental effects of coal mines: “The paddy field becomes black. When we clean the paddy, there is a lot of dust from the coal mines.”

Loss of Tribal Sacred Spaces

After Mahan II began operating, the ensuing displacement and destruction of land and forest led to the destruction of many sacred sites. These included the sacred water pond Mahdani, revered by Oraons/Gonds and other Tribes, along with other dhodhi (sacred water bodies), and Dev Gudi (village spirits). Chaura village is currently home to many ancestral spirits, such as Ghasdanav, Baair Mahadev, and Bar Devta, who are paid offerings by the community during specific seasons throughout the year.

Thuiya Baiga, one of the priests from Chaura village, pointing to lost sacred sites.

Thuiya Baiga, 60, one of the eldest priests in Chaura village, gives a detailed account of the spiritual world of the village that has been, or is threatened to be, destroyed by the Mahan II/III/IV coal mines. In Baisakh (April-May), there is a ritual for Baair Mahadev, where everyone takes part. Another ritual called Kharboj takes place near a khanihaar (small courtyard used for cleaning or drying agricultural products) that involves giving offerings to all the ancestral spirits of the village. In addition, there are annual rituals for kothaar (the house of cattle), where a sacrifice is made for the spirits. During Mahadev, people make kathoori, which involves the wedding of ancestral spirits—a grand event where everyone from the village, regardless of the Tribe, takes part. There is also an annual ritual of sacrifice at the sacred groove called Sarna, which is considered home to Persa Pen, or the chief ancestral spirit of the Gond Tribe. “All these different rituals and festivals require sacrifice of specific-colored animals,” Thuiya explains. “Ghasdanav and Paath required a goat sacrifice every five years. Other rituals require white/black chickens, and so on.”

When Mahan II was set to be opened in 2008, an SECL official offered to pay Baiga to perform the inauguration rituals. “I told them, I won’t take their money and I won't go to the event,” he says. “I do not know what rituals to perform for the opening of a mine…I don’t know what spiritual practice is required for the inauguration of a coal mine.” Thuiya recalls another incident when mining was being done near a sacred tree, and SECL’s machine broke. “It was then they started looking for a baiga,” he says, “but I never went.”

Baiga says that among the sacred spirits destroyed by Mahan II, Mahdaani was the most important. It was a sacred pond where Oraon and Gond people used to make offerings once a year. However, once the pond got destroyed by the SECL, they couldn’t replace it or move it, unlike other ancestral spirits, which were moved to a different location. “Now people have stopped coming for the annual ritual of Mahdaani,” he says. “It is beginning to lose its significance.” Baiga believes that the community is facing many problems since the destruction of sacred places such as Mahdaani. “Diseases are being spread to animals and people as a result of loss of spirits,” he says. The forest spirits are still safe from the mines, including Kuwar Paat Devta. “If we don’t pay him offerings, our paddy yield reduces. If we pay offerings, the yield is good,” Baiga says.

SECL’s Environmental Management Claims vs. Reality

SECL claims that its primary concern in environmental management is “sustainable development” and “responsibility towards environmental performance.” Its fiscal report notes that environmental measures are embedded as an integrated subsystem of mine management, such as transporting coal by closed conveyors for loading onto rail wagons, and that the company “has undertaken several measures to mitigate the aspect of dust in its mining areas” through mobile water sprinklers, fogging machines, and mechanical road sweepers. The report claims that Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Systems with digital displays have been installed in different areas for monitoring air quality. However, in reality, these claims fall flat.

In order to mitigate deforestation, SECL claims that it has undertaken “massive multi-species plantations for biodiversity conservation and topsoil management,” including the planting of 1.3 million saplings over an area of 500 hectares in 2024-25, and a total of 30 million saplings since 1986. SECL has also signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh Rajya Van Vikas Nigam for reforestation for the next five years. Additionally, the company claims that it has undertaken “roadside plantation and plantation of overburden dump, dump slopes, around infrastructures and residential colonies” to ensure a clean environment and minimize pollution around coal mining areas.

The scale of destruction caused by the Mahan II coal mines. The photo only shows a small portion of the larger coal field, as seen in the satellite imagery.

SECL currently employs a workforce of 37,523, of which only 19.1 percent, or 7,193, belong to Scheduled Tribes. The small percentage of the Tribal population employed in the company reveals that, contrary to promises, providing jobs in return for the loss of land has not taken place. Most of the people employed from local Scheduled Tribes are contractors, as the company predominantly employs workers from outside. Villagers mock the contract jobs given by the company as being comparable to the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA)—a recently repealed social welfare program that was supposed to provide guaranteed employment.

The Corporate Social Responsibility section of SECL’s 2024-25 fiscal report consists of only two small paragraphs. It claims that “engaging with local communities and working towards their development” is an integral part of the company’s business strategy and that the primary beneficiaries of CSR are the project affected persons within a 24 km radius of the project. There is no detailed description of the CSR initiatives undertaken by the company in the previous year’s annual report, and both versions contain identical wording. SECL’s claims of CSR initiatives are nowhere close to what was promised to the community—that two percent of total profit would go into CSR initiatives.

Details from the CSR section of SECL’s website show that, among the CSR activities, in 2023, Balrampur district authorities were given financial assistance of 9.9 million rupees (approximately $108,000 USD) for the construction of four Farmers Community Irrigation Projects in Chaura village. The same year, tubewells were installed in Chaura village at a cost of 480,000 rupees ($5,200 USD). In 2021, SECL spent 450,000 rupees ($4,900 USD) on borewell pumps in Chaura village. The total sum of these activities represents a minuscule fraction of the profits made from Mahan II, which displaced entire communities.

Pollution Endangers Communities, Animals, and Biodiversity

Agam Ram Poya, a Chaura villager, and Ramsundar, a former sarpanch, took me to the mines and showed me the pipes from which water was being released into the village’s clean water source. Ramsundar reiterates that the expansion of Mahan II to III and IV happened through gram sabha, however, without the proper consent of the communities. Poya says that everyday blasting in such close proximity to the mines has resulted in the settling of dust on crops and in houses, as well as causing cracked walls. The villagers say that the groundwater level in the village has significantly gone down, and they do not have access to clean drinking water.

According to last year’s report, the Jagannathpur Open Cast Coal Mine discharges about 2,659 cubic meters of groundwater daily, which is treated and then used to irrigate 500 acres of farmland. The Area General Manager of SECL Bhatgaon region, where Mahan II is located, says that “Groundwater from our mines is collected, treated, and supplied to villages for farming after obtaining necessary permissions from the Central Ground Water Board. This water is also used for dust suppression and machine operations within the mines, with the surplus directed to community irrigation.”

Waste water from Mahan III and IV coal mines is discharged into the clean water body adjacent to Chaura village. The water is used by the villagers for agriculture and other needs.

However, the reality on the ground tells a different story. The water released from the Mahan III and IV coal mines is directly released to the water body adjacent to Chaura village, and it does not go through treatment, as can be clearly seen in the image above.

Paddy fields in Chaura village, with water being released to the water body in the background.

Mahan II's coal dump beside farmland, over which the vegetation is growing. The unused land has still not been given back to the community.

Chaura's water body flows alongside the village, but gets polluted with the water released from the coal mine.

While pollution and lack of compensation and rehabilitation are the main issues raised by the people, the entire establishment of the SECL mines without due process is the most important story. There are many coal waste dumpyards across the mines, as pictured above. The villagers in Chaura argue that since Mahan II has been mined to capacity and now lies vacant, the land should be returned to the villagers. As per the law, the mining company is supposed to have a post-closure plan for the mines. However, no such plan was prepared for Mahan II; instead, the land has been given to the forest department.

Coal dump mount on the side of Chaura village’s water source. During rains, the coal dust goes into the water bodies used by people and animals, and for agriculture.

Mahan II is deserted after being extracted to capacity. The company has yet to implement any post-closure plan, and the land lies barren.

For coal and other mining activities, it is mandated that the companies issue a post-closure plan before the initiation of the project. However, no such plans were shared with the community, and no information about any post-closure plan can be found in the publicly available documents for Mahan II. Since Mahan II was mined to capacity and subsequently closed, and the land is now unused, villagers ask, “Why can’t it be allocated back to us?” “We could do whatever we want with that land,” Poya says.

While the company has planted some trees on top of the coal dumps and left the water released from the mines open, the barren land is of no use to the community. A post-closure plan could mean that some biodiversity could be recovered in the used land, if the Mahan II area were given back to the communities. “We have heard that the company is giving it to the forest department,” Poya says. Instead of returning the land to its original owners, the transfer of land to the forest department further reflects how Tribal communities are invisibilized in the overall mining policies of companies such as SECL.

---Akash Poyam (Gond/Koitur) is a writer and researcher based in Chhattisgarh, India. He is a contributing writer for The Caravan Magazine, New Delhi. Formerly a member of the faculty at the Asian College of Journalism, Chennai, he holds a master’s degree in Sociology from the University of Hyderabad. He is a 2025 Cultural Survival Indigenous Journalism Fellow.

Top photo: Agam Ram Poya and Ramsundar sit facing Mahan II and III open-cast coal mines near their village.

All photos by Akash Poya.