By Lucas Kasosi (Maasai, CS Intern)

Among the Maasai, wisdom often arrives in the form of proverbs; concise truths distilled from generations of living close to the land. One such saying is Memanyayu Meleeno: “You cannot live where you have not gone and checked.” More than words, it is a compass. For centuries, it has guided decision-making, teaching that real knowledge does not come from speculation or decree, but from experience; from walking the land, listening intently, observing with care, verifying through lived reality, and returning with truth. At the 4th PACT (Pathway Alliance for Change and Transformation) International Conference on Indigenous-Led Research, held in Narok, Kenya, from August 26 to 28, 2025, this proverb was more than a saying; it became a guiding thread.

PACT is a global alliance of Indigenous organizations and leaders from Africa, Asia, the Americas, and the Pacific, created to reclaim research as a tool for liberation rather than oppression. It seeks to replace externally imposed studies with Indigenous-led, community-centered knowledge creation that strengthens self-determination, resilience, and justice. As one of its founders, Samuel Nguuffo of Cameroon, often reminds, “Research is an instrument of power. For centuries, it was used to legitimize false solutions. But Indigenous-led research is about life.”

It was in this spirit that the Narok gathering was framed; not as a conventional academic event, but as a reclamation of knowledge itself. In his keynote address, Prof. Sarone Ole Sena, a revered Maasai scholar, explained how the proverb reflects an Indigenous research ethos:

“Memanyayu Meleeno is evidence that Maasai, like all Indigenous Peoples, have always been researchers. We studied the stars, the rains, the grasses, the cattle, and the springs. Research was never alien to us; it is life itself.”

This conference, hosted by the Indigenous Livelihoods Enhancement Partners (ILEPA), embodied that truth. For three days, Elders, youth, women, government officials, academics, donors, and international allies gathered on Maasai land to reaffirm that Indigenous Peoples must lead the research that shapes their futures.

A Gathering Rooted in Land

The setting itself was symbolic. Narok County is the heartland of the Maasai, where pastoralists have lived for generations alongside wildlife, managing grasslands and watersheds with customary governance systems. Hosting the conference here, not in an anonymous capital hotel, was a declaration: research belongs on the land of the people it concerns.

Participants did not just sit in halls. They walked the hills of Maji Moto, visited the sacred hot spring, planted trees, and met community leaders at the Muitatin Resource Centre. Each site visit carried a message: knowledge is not abstract. It is embodied in springs, in grazing herds, in cultural rituals, and in people’s lived realities.

Changing the Narrative

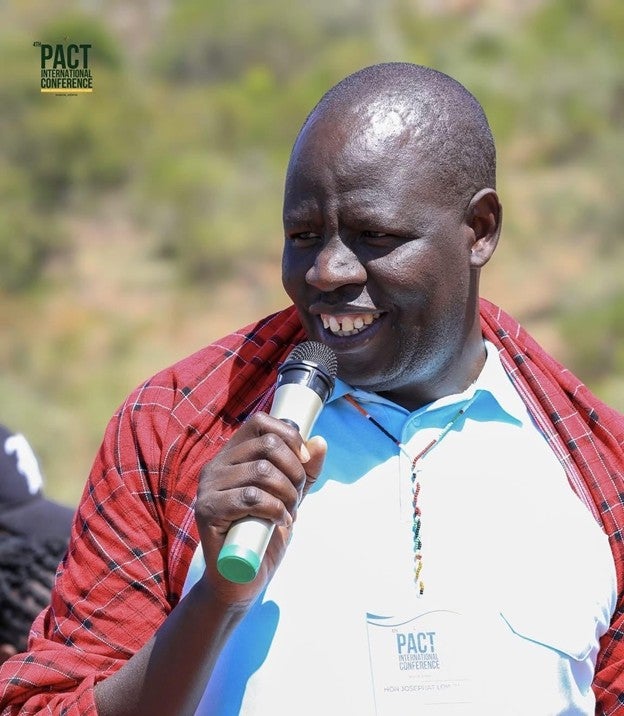

Joseph Ole Simel, Executive Director of the Mainyoito Pastoralist Integrated Development Organization (MPIDO), delivers the keynote address at the opening of the 4th PACT International Conference.

The opening ceremony reminded everyone this was no ordinary meeting. Joseph Ole Simel (Maasai), a leader with decades of advocacy experience, declared:

“Today is a day we must remember for many years to come. It is very unique that the global community meets here in Maasai territory to discuss questions that face us. This meeting is the beginning to change the narrative.”

The narrative he spoke of is the long history of extractive research; studies done on Indigenous Peoples, without consent, often with devastating consequences. Such research has been used to justify land grabs, conservation exclusion, and policies that shattered pastoral economies. But Narok flipped the script. Indigenous Peoples spoke as researchers, not subjects. They spoke as custodians of knowledge, not as case studies.

Samuel Nguuffo, senior founder of PACT from Cameroon, captured it sharply:

“The story of Indigenous Peoples was told by foreigners, through their perception; totally biased. The result has been false solutions and omissions. Until Indigenous Peoples tell their own stories, the world will continue to fail.”

For Nguuffo, the failures of dominant systems; climate change, biodiversity collapse, food insecurity; are not accidental. They stem from ignoring Indigenous philosophies of life, where well-being is felt, seen, and touched, not measured in GDP.

ILEPA: Walking with Communities

Central to this transformation is ILEPA, the conference host. Founded in 2009 by Stanley Kimaren Ole Riamit, ILEPA emerged from Maasai struggles over land rights and governance. Its name, from the Maa word ilepa, means “to arise” or “to ascend.”

“We realized that land struggles weren’t just about community conflicts,” Riamit explained. “They involve governments, business actors, lawyers, and powerful institutions. That complexity demanded an organized, evidence-based response. That’s how ILEPA was born.”

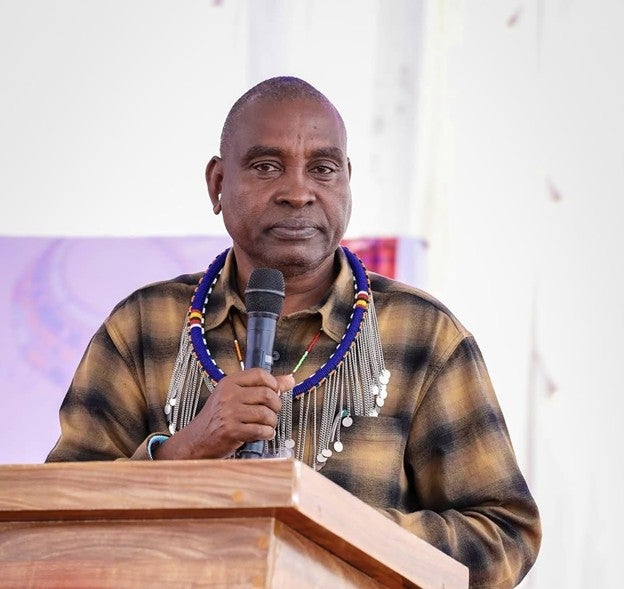

Kimaren Ole Riamit, Executive Director of ILEPA, addresses participants during the 4th PACT International Conference in Narok, Kenya.

Over 15 years, ILEPA has grown from a modest grassroots initiative into a regional force for land justice, climate advocacy, and Indigenous governance revitalization. Yet its philosophy is not to lead forever. “We succeed when communities no longer need us,” Riamit reminded participants. “Our success is making ILEPA irrelevant by empowering communities to rise, speak, and act for themselves. That is the real meaning of self-determination.”

The Wound of Extractive Research

For many participants, the pain of extractive research was not abstract but lived. Ole Simel recalled the disastrous policy of land individualization, promoted by outsiders in the name of modernization. Titles fragmented Maasai land, destroyed communal grazing, and pushed families into poverty.

“Selling wealth to buy poverty,” Ole Simel lamented, describing how privatization severed ecological balance and social safety nets. “Research has been part of colonization; that is the reality,” Simel said. “But research led by Indigenous scholars makes all the difference. Without our own data, we cannot influence policy. Without evidence, we remain voiceless.”

This message resonated across regions. Indigenous leaders from Cameroon to Nepal, from the Philippines to Tanzania, shared similar experiences of “development” projects imposed through studies that framed their communities as primitive, resistant to change, or simply invisible.

From left: Milka Talaam, Prof. Elifuraha Laltaika of Tanzania, and Commissioner Caroline Lentupuru

Milka Talaam, an Indigenous Sengwer woman and advocate with the Rights and Resources Initiative, spoke with equal force:

“We don’t have to wait for outsiders to research us and give results to themselves. Our grandmothers are professors too. When we sit with them, when boys go out with fathers to care for resources; that is learning. That is research.”

She reminded donors and academics that Indigenous Peoples’ sense of time is not clock-driven: “Our time is when cows come home, when the season changes. If you want meaningful consultation, respect our time.” Her conclusion was bold: “Reverse the arrow of capacity building. Let Indigenous Peoples teach the professors.”

Universities as Neighbors, Not Extractors

One institution taking that call seriously is Masai Mara University (MMU). Samson Mwaboga, representing MMU, emphasized:

“Our strategic location positions us at the intersection of Indigenous knowledge and academic excellence. Research questions must emerge from community needs, and findings must return to benefit those communities.”

The university’s identity is tied to the “Five M’s”: Maasai Mara Game Reserve, Mau Forest, Mara River, Maa culture, and Maombi kwa Wote (spirituality). Its strategic plan includes funding for cultural centers, medicinal plant programs, and an Indigenous knowledge journal. “The future of environmental conservation and sustainable development cannot be achieved without Indigenous leadership,” Mwaboga affirmed. This was not lip service; it was a declaration that survival of the university depends on survival of the cultures around it.

Policy and Government Recognition

Encouragingly, government officials at the conference acknowledged that Indigenous evidence is indispensable for policy.

Commissioner Caroline Lentupuru of the National Gender and Equality Commission, herself an Indigenous IlChamus woman, declared: “We cannot advise the government without facts. Research becomes very, very important. If research is done and does not add to a solution, then what was the value?”

She highlighted NGEC’s studies on Indigenous girls’ education across 18 counties, designed to influence national ministries.

Josphat Lowoi, Director of the Minorities and Marginalized Affairs Unit in Kenya, addressing the Majimoto community during the visit.

From the Office of the President, Hon. Josphat Lowoi issued a cultural warning: “This land is not just soil. It is your history, your lineage, your future. Better you don’t marry than sell your land to pay dowry.” Their remarks signaled a shift: state institutions beginning to see Indigenous-led research as essential for policy, not peripheral.

Financing Indigenous Futures

Yet recognition alone is not enough. Communities need resources to implement their visions. Sessions on finance explored how biodiversity and climate funds can flow directly to Indigenous Peoples and local communties, rather than trickling through multiple intermediaries. The message was consistent: funders must trust communities to decide their priorities. Proposals should not be exercises in donor jargon; monitoring should reflect community indicators of success; healthy springs, thriving herds, vibrant languages. As Ole Twala summarized: “Indigenous Navigator means: no donor dictates, no imposed timelines. The community decides.”

Narratives as Power

The conference also underscored that data alone is not enough. Narratives shape policy and perception. For too long, media and research alike have cast Indigenous pastoralists as environmental destroyers. Ole Simel countered this stereotype:

“Pastoralism is one of the best ways to conserve the environment. We are not destroyers; we are custodians.”

Delegates called for investment in Indigenous media, community radio, youth-led film, language apps, to tell stories in their own voices. Because without narrative sovereignty, even evidence risks being ignored or distorted.

Maji Moto: Where Struggle Meets Resilience

The most powerful moments came during the visit to Maji Moto, the birthplace of ILEPA. Known in Maa as Enkare Nairowua; “hot water”, the site takes its name from the hot spring that flows through volcanic rock. For the Maasai, the spring is sacred. For ILEPA, it is a symbol: of resilience, of renewal, of justice fought for and won.

Conference participants gathered with the Majimoto community on the hill, engaging in dialogue on land rights, cultural heritage, and Indigenous resilience.

Land Justice Victory

Here, the community had faced betrayal. Leaders colluded with surveyors to manipulate subdivisions of the Maji Moto Group Ranch, 48,000 hectares of ancestral land. Some received 25 times the average allotment. Families were left landless, markets and schools grabbed. One Elder, Ole Nasi, recalled: “Every man now has his own place. We never thought the land would return; but truth cannot be erased. We are the first group to fight for land and win. Others give up or join the enemy, but Majimoto held firm.”

A group of Maasai students began documenting irregularities and brought their findings to ILEPA. With meticulous preparation; mapping parcels, exposing violations, and mobilizing grassroots support; ILEPA helped launch a landmark legal battle. In Case ELC 268 of 2017, the community challenged fraudulent titles. For seven years, they packed the court at every hearing, turning a private case into a public cause. Against the odds, in 2023, a Kenyan court canceled the illegal titles and returned more than 600 parcels of land to rightful owners. It was the first time in Narok that titles had been revoked and reissued to an Indigenous group, a precedent now studied across East Africa.

“Facts are stubborn,” Ole Riamit reflected. “Even before a corrupt judge, facts resist manipulation. Time cannot erase truth. Lies delay it, but they cannot defeat it.” The victory reverberated far beyond Narok. Delegates from Cameroon, Nepal, Indonesia, and the US saw in Maji Moto a global lesson: land grabs can be reversed. Evidence, persistence, and community unity can reclaim history.

As one Nepali leader reflected: “We face the same struggles. I will return home to advocate, and I invite you to Nepal to see our Indigenous lives.” A delegate from Cameroon added: “We are not recognized where we were born. But Majimoto gives me courage; proof that truth wins.”

Research that Fits

At Maji Moto hill, Ole Riamit invoked another proverb: Tenibor Enamuke, niririki kewon; “When you cut a shoe for yourself, it must fit.” It was a metaphor for community-driven research. Only data collected and interpreted by Indigenous Peoples themselves, he argued, can truly “fit” their realities. “Data on Indigenous People, by Indigenous People, for Indigenous People,” Riamit said. “That is the shoe that fits. That is what justice requires.”

This principle came alive in the Indigenous Navigator Project, a 14-country initiative in which Maji Moto participated. Unlike conventional donor models, there were no lengthy proposals or imposed indicators. Communities themselves identified their needs, set priorities, and implemented solutions.

Normejooli, an Indigenous woman leader, shares her community’s struggles and triumphs during the Majimoto hill visit.

For Maji Moto, the priority was clear: health. Women had been dying on the road to distant hospitals during childbirth. Youth collected data, Elders validated it, and the community chose to build a maternity wing at Maji Moto center, a site accessible to many and sacred to the Maasai.

Within months, the new hospital had already served more than 200 women. Mothers who once walked for days could now deliver safely close to home. “The hospital is a victory of our own voice,” Normejooli, an Indigenous woman said. “ILEPA only walked with us.”

Innovations for Survival

The Maji Moto visit also showcased community innovations that blend traditional knowledge with adaptive strategies. To counter shrinking pastures and harsher droughts, ILEPA and the community introduced rotational Sahiwal bulls; 12 bulls that have serviced over 500 cows, strengthening breeds and boosting milk and meat yields. Gabriel Lepore, a community member, testified:

“I sold my bull in hard times. Then I borrowed the community bull. Today I have 14 more cattle. The bull even served my grandfather’s cows; and I returned it. This is wealth that multiplies.”

In addition, four massive hay silos, each capable of storing 20,000 bales, have changed pastoralist practice. The old model was to move cattle to pasture. The new wisdom: “Bring pasture to cattle, not cattle to pasture.” This shift helped families survive drought without abandoning homesteads. These innovations are not charity projects. They are examples of Indigenous-led resilience, rooted in local priorities and scaled with evidence.

Global Resonance

For participants, Maji Moto was more than a visit; it was a mirror. Delegates from across continents recognized their own struggles in the Maasai story, dispossession, corruption, exclusion, but also resilience, creativity, and victory. A US delegate reflected:

“Even after 400 years, land is being returned. Persistence, patience, and hope are our strongest tools.”

An Indonesian delegate laughed as he compared landscapes: “Our lands are the same; except giraffes! You are further ahead, but we are the same people with the same struggles.” Samuel Nguuffo put it plainly: “Indigenous Peoples are the only ones who have kept their connection with nature for centuries. That is the knowledge we need now.” These voices confirmed that Maji Moto’s lessons are global. Evidence-based advocacy, intergenerational leadership, and unity in struggle are not Maasai strategies alone. They are the shared DNA of Indigenous survival worldwide.

Toward a World Where Life Matters More Than Money

In closing, what did Narok give us? It gave us a vision. A vision where research is no longer a weapon of colonization but a covenant with land and people. Where Elders are professors, youth are archivists, universities are neighbors, governments are listeners, and donors are partners.

Indigenous youth actively participating in the 4th PACT International Conference.

It gave us courage: the courage to name exploitation for what it is, and to propose alternatives rooted in dignity. It gave us unity: across continents, Indigenous voices echoed the same call; for self-determination, resilience, and solidarity. And it gave us responsibility: to ensure that the words spoken in Narok translate into laws, budgets, curricula, and institutions that finally respect Indigenous governance of knowledge.

At the heart of it all is the spirit of ILEPA. Like the spring that gave Maji Moto its name, ILEPA has become a source of renewal; bubbling with the power of evidence, the warmth of solidarity, and the persistence of hope. As Stanley Kimaren Ole Riamit reminded participants: “We succeed when communities no longer need us.”

The measure of success will not be another conference, another report, or another donor project. It will be communities empowered to define their own research, their own education, their own futures. As Prof. Elifuraha Laltaika of Tanzania concluded: “This is what Vicky Tauli-Corpuz meant by self-determined development. Not fishponds in dry villages, but what communities choose for themselves. This is a concrete example.” And as Samuel Nguuffo of Cameroon put it: “We want a world where life matters more than money, where well-being is not measured by numbers but felt, seen, and touched.”

From Narok to the Amazon, from the Himalayas to the Arctic, the call of this conference is clear: Indigenous Peoples are not subjects of research; they are researchers of their own lives. They are not obstacles to development; they are architects of sustainable futures. The Maasai proverb still guides us: Memanyayu Meleeno. To live well, you must go, see, and learn. The people who gathered in Narok have gone, they have seen, and they have learned. Now, they are ready to lead. And the world; policymakers, academics, funders, and citizens alike, must be ready to follow.

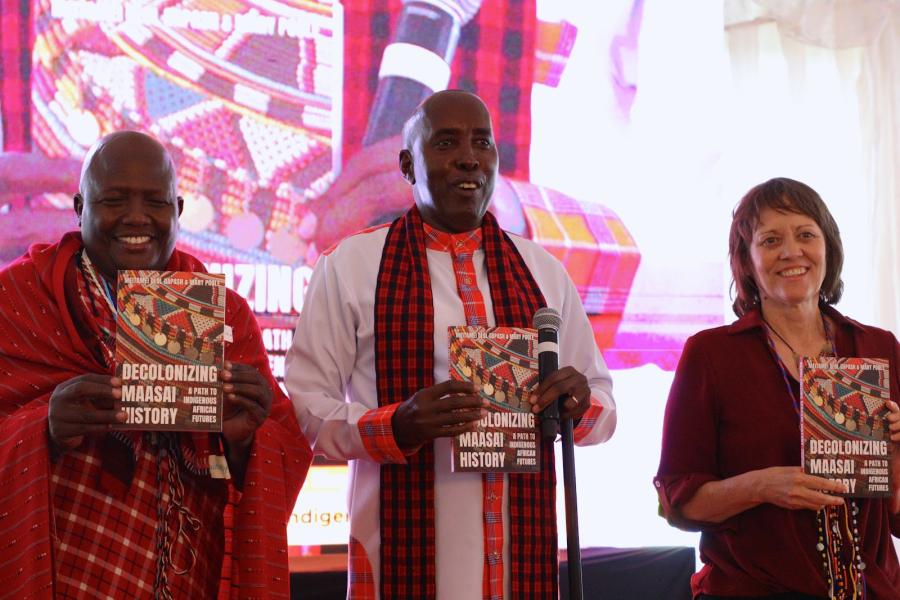

Top photo: Indigenous leaders, scholars, and policymakers united at the PACT Conference to advance self-determined development.

All photos by ILEPA