By Georges Dougnon (Dogon, CS Staff)

Rural women play a crucial role in the Sahel region, particularly in Mali. According to 2021 data, women represent 50.4% of Mali's total population, with 52% living in rural areas.

The daily life of rural women is one of courage and sacrifice. Many who grew up in the village know this reality, that of the woman known as “la villageoise.” She knows neither washing machines nor running water. She lives in a world where getting water to drink is a daily struggle. Her life is one of courage and dedication.

The village woman gets up at the crack of dawn to collect water, starting at 4:00 a.m. At this time of day, she's the only one up and gets ready after washing to fetch water. Her first destination is the village well, located anywhere from one to five kilometers away. Basin on her head, scarf in hand, baby strapped to her back, she walks alone or in a group, braving the darkness. In this region of the Sahel, wind, dust, and sometimes fog accompany her steps.

Along the way, she meets other women from the village. Together, they chat, sing, and share moments of solidarity. Arriving at the well, they organize themselves to draw water, especially for those with neither donkey nor camel to help them. The sound of the pulley, worn by time, punctuates their efforts. They fill several basins and buckets, then help each other carry their heavy loads back to the village.

After two or three turns at the well, she sets about preparing breakfast and heating water for her husband. As in every family, she piles the millet, lights the fire, and puts the pot down—a daily gesture full of tenderness that enables her to obtain the millet porridge that will be served for breakfast to her husband and children. While her husband is away in the fields, she is still busy preparing breakfast.

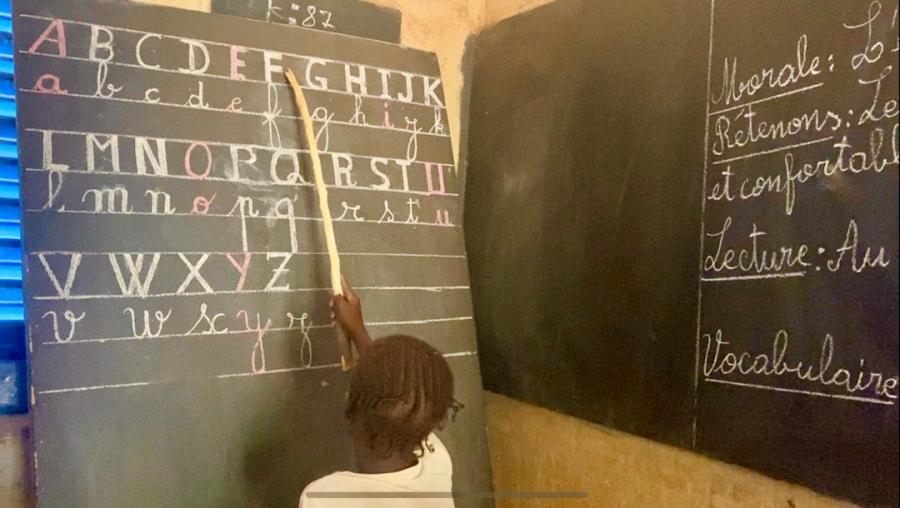

Before that, she has to sweep the plot, make the condiments, wash the dishes and the laundry, and get the children ready for school. With the baby on her back, she starts to work on cooking the tô, a traditional millet or sorghum-based dish with a baobab or okra leaf sauce.

Amid the effort of lighting the wood, which is often difficult, the smoke she breathes, the heat of the kitchen, and the children's cries, she manages to bring the good tô ready at midday to her husband, a hot dish that she will put in the traditional bowl and serve hot. She will take it to the field for her husband. While her husband eats his lunch in the field and rests, she helps him cultivate the field and then breaks up the deadwood that will be used to cook the evening meal.

After her husband's meal, it is her turn to eat. She chats a little with her husband, and as he returns to the field after his break, she gathers her cooking wood and returns home to cook dinner for her family. She's also the one who heats up the water so her husband can take a hot bath after work. She serves dinner to her husband and children in the evening, then puts them to bed.

She only gets a moment's respite when the children and husband are in bed. Sometimes, she is woken by the infant she has to breastfeed or soothe if the baby can't sleep.

Laya, a Malian living in Dourou in the Bandiagara region, married for 25 years, says, “This has been my life since I was a young bride. For me, all this is normal. This is how women live here. We work from morning to night for our family. Rest is rare, but you get used to it. What keeps me going is seeing my children grow up healthy and my family happy. However, I dream that one day my daughters will have better living conditions. They deserve more than what we've had.”

This is the daily life of many village women, the daily life of a woman who sacrifices herself day and night to take care of her family. Village women, essential yet often forgotten despite their immense contribution to society, remain invisible. Their needs are ignored in political and social decisions, and their rights are poorly defended. They frequently live in environments marked by poverty along with the vagaries of climate and conflict, and have to cope not only with their exhausting daily routines, but also with abuse and injustice.

It is time to recognize the strength of village women and their essential role in society. It is by improving their living conditions that we will build a more just and equitable future for all.

Photos by Zeina Sidibé who has a project on highlighting women's lives called "Awn Ka So" (Our Home).

Le quotidien de la femme rurale au Sahel.

Par Georges Dougnon (Dogon, Personnel de CS)

La vie des femmes rurales appelée “ la villageoise” est un un quotidien de courage et de sacrifices.

Beaucoup de ceux qui ont grandi au village connaissent cette réalité, celle de la femme que l'on appelle "la villageoise". Elle ne connaît ni machine à laver, ni robinet d’eau courante. Elle vit dans un monde où, pour avoir de l'eau à boire, il faut mener un véritable combat quotidien. Découvrons sa vie, son courage, et son dévouement.

Un lever aux aurores pour la quête d'eau qui commence à 4h du matin, a cette heure de la journée, elle est la seule déjà debout et se prépare après sa toilette à aller chercher de l’eau. En route pour le puits du village, souvent situé entre 1 et 5 km de distance, est sa première destination. Bassine sur la tête, foulard en main, et le bébé attaché dans son dos, elle marche seule ou en groupe, bravant l’obscurité. Dans cette région du Sahel, le vent, la poussière, et parfois le brouillard accompagnent ses pas.

Sur la route, elle croise d’autres femmes du village. Ensemble, elles discutent, chantent, et partagent des instants de solidarité. Certaines allaient même leur bébé en marchant.

Arrivées au puits, elles s’organisent pour tirer l’eau, surtout pour celles qui n’ont ni âne ni chameau pour les aider. Le bruit de la poulie, usée par le temps, rythme leurs efforts. Chacune remplit plusieurs bassines et seaux, puis elles s’aident mutuellement à porter leurs lourdes charges jusqu’au village.

Après avoir effectué 2 à 3 tours au puits, elles se mettent à préparer le petit déjeuner, chauffer de l’eau pour leur mari. Comme dans toutes les familles, elle pile le mil, allume le feu et pose la marmite. Un geste quotidien, rempli de tendresse, qui lui permet d'obtenir la bouillie de mil qui sera servi au petit déjeuner à son mari et aux enfants.

Pendant que le mari part au champs, elle se met encore à préparer le déjeuner.

Avant, elle doit balayer la concession, faire les condiments, faire la vaisselle et parfois la lessive, préparer les enfants pour l'école et le bébé au dos, elle commence les travaux pour cuisiner le bon tô (plat traditionnel à base de mil ou de Sorgho) à la sauce de feuilles de baobab ou de gombo.

Entre le bois souvent difficile à allumer, la fumée qu'elle respire, la chaleur de la cuisine et les pleurs des enfants, elle s'arrange à apporter le bon “tô” prêt à midi à son mari.

Un plat chaud qu’elle mettra dans l'écuelle traditionnel et qui sera servi a chaud. Il sera porté au champs à son mari. Pendant que le mari mange son déjeuner au champ et se repose, elle l'aide à cultiver le champ et ensuite casse du bois mort qui servira à cuisiner le dîner du soir.

Après le repas de son mari, elle mange à son tour, discute un peu avec son mari, et au moment où ce dernier après sa pause regagne le champ, elle ramasse ses bois de cuisine et rentre à la maison afin de faire le dîner à sa famille.

Elle est aussi celle qui chauffe de l'eau pour que le mari prenne un bain chaud après le travail. Elle sert le dîner à son mari et ses enfants , le soir, pour ensuite mettre les enfants au lit.

Elle n'a un moment de répit que lorsque les enfants et le mari sont au lit. Parfois, elle est à plusieurs fois réveillée par le nourrisson qu'elle doit allaiter, ou souvent bercer si ce dernier n'arrive pas à dormir.

Laya, Malienne vivant à Dourou, dans la région de Bandiagara, mariée depuis 25 ans, raconte :

"C’est ma vie depuis que je suis jeune mariée. Pour moi, tout cela est normal. Ici, c’est comme ça que les femmes vivent. On travaille du matin au soir pour notre famille. Les moments de repos sont rares, mais on s’y habitue. Ce qui me fait tenir, c’est de voir mes enfants grandir en bonne santé et ma famille heureuse. Cependant, je rêve qu’un jour, mes filles aient des conditions de vie meilleures. Elles méritent plus que ce que nous avons connu."

Ceci est le quotidien d'une " villageoise" un quotidien auquel on peut ajouter encore pleins d'autres occupations parallèles, le quotidien d'une femme qui se sacrifie jours et nuits pour prendre soin de sa famille.

La femme villageoise, oubliée mais essentiel malgré leur immense contribution à la société, restent souvent invisibles. Leurs besoins sont ignorés dans les décisions politiques et sociales, et leurs droits sont peu défendus. Elles vivent parfois dans des environnements marqués par la pauvreté, les aléas du climat et les conflits, et doivent faire face, en plus de leur quotidien harassant, à des formes de maltraitance et d’injustices.

Il est temps de reconnaître leur force et leur rôle essentiel dans la société. C’est en améliorant leurs conditions de vie que nous construirons un avenir plus juste et équitable pour toutes.

Top photo by UN Photo/Ian Steele.

Photos by Zeina Sidibé who has a project on highlighting women's lives called "Awn Ka So" (Our Home).