By Elisa Ribeiro (CS Intern), Daniela Mostacilla (Nasa), and John Sabogal

In a rural area of Colombia’s central mountain range, Carmen Rosa Piamba (Nasa) prepares to leave her home in Caldono, a town surrounded by mountains and coffee plantations in the department of Cauca. Like every other Saturday, she takes a chiva—the colorful, typical bus of the Colombian Andes—to travel along winding roads and arrive at 8:00 a.m. at the House of Memory and Youth in the town center. Since March 2025, Saturdays have been the meeting day for about twenty-five women from the Nasa Indigenous community who share something else in common: they are searching for a family member who disappeared during the war. Walking together, the Indigenous women support each other with every step, like threads in a collective tapestry that seeks to connect them through their struggles and hopes of finding their loved ones. They gather to share their pain and knowledge, to support each other on the complicated path of the search, a path some have walked for decades, and others take up from their aging or deceased parents who never knew the truth about their missing loved ones. Some have succeeded in having their relatives' remains returned, but for other women, this space represents the first safe place to talk about what happened. Words, knitting, and embraces mark the rhythm of each encounter, where the women searchers share their memories and plan paths together to find those who are missing. Each woman has played a fundamental role in the resistance against the armed conflict that has plagued their territories for decades. With love and strength, even in the face of fear, these women continue to fight for the dignity of their loved ones.

The Collective Wounds of Disappearance

Following the 2016 Peace Agreement between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP) guerrillas and the Colombian State, one of the commitments agreed upon as part of transitional justice is the search for all persons disappeared during the internal armed conflict. From a humanitarian, rather than a judicial, perspective, the State committed to guaranteeing the right to the truth and locating the whereabouts of more than 130,000 people disappeared due to the war—a long and complex cycle of violence that, according to historians, has extended since the second half of the 20th century, but which, for Indigenous Peoples, is preceded by the extermination that resulted from colonization and the struggles for nation-Statehood.

Southwestern Colombia, and particularly the department of Cauca, where around 15% of the population self-identifies as belonging to an Indigenous group, has been one of the epicenters of violence. The disappearance of people in different circumstances associated with the armed conflict, from the recruitment of minors to forced disappearances by State or paramilitary agents, is an open wound in many Indigenous territories. In turn, many sacred and community sites have been desecrated by clandestine graves used by armed groups to hide the bodies of their victims.

Carmen Rosa, one of the hundreds of women searching for their missing loved ones in Caldono, is looking for her brother, Luis Carlos Piamba Bomba, who, before turning 18, was recruited by the FARC in 2012, and whose whereabouts remain unknown. For some years now, Carmen has taken up the search that her parents began when Luis Carlos disappeared. This is a struggle that unites generations on the path to knowing the truth. In their words: “The search for me and my family is about bringing closure and achieving peace. That doesn't mean it ends here; it's just the end of one part of a story with many other parts. This implies that we, as practitioners of (Indigenous) spirituality, allow some freedom for the person we are searching for, because until we find them, no one can be at peace, nor can they rest in peace if they are in another place. And we, as searchers, cannot be at peace until we have some answers.”

Despite this context, Cauca has also been the epicenter of significant social and resistance movements. Since the early 1970s, Indigenous communities have created the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC), fighting for land, their own education, and autonomy, and have become a leading organization and resistance movement for Indigenous Peoples in Latin America. Indigenous women have been consolidating regional organizational processes such as the CRIC Women's Program and the Women's Network of the Çxhab Wala Kiwe - Association of Indigenous Councils of Northern Cauca. Some Indigenous women searchers have participated in these spaces and, in recent years, have sought to create their own spaces for encounter and exchange, demanding their right to the truth and making visible their role as peacebuilders.

U’ywe’sx Çxhaçxha Yaakxsaa: Brave Women of Caldono

Indigenous women have been conquering arenas of struggle, refusing to forget their disappeared loved ones despite the pain left by the armed conflict. Amid the chaos of violence, their voices have echoed through valleys and mountains, confronting the uncertainty of absence. With care and the characteristic courage of Nasa women, they have raised their voices powerfully amidst the weapons and have not ceased demanding answers about their disappeared fathers, children, siblings, nephews, and other relatives.

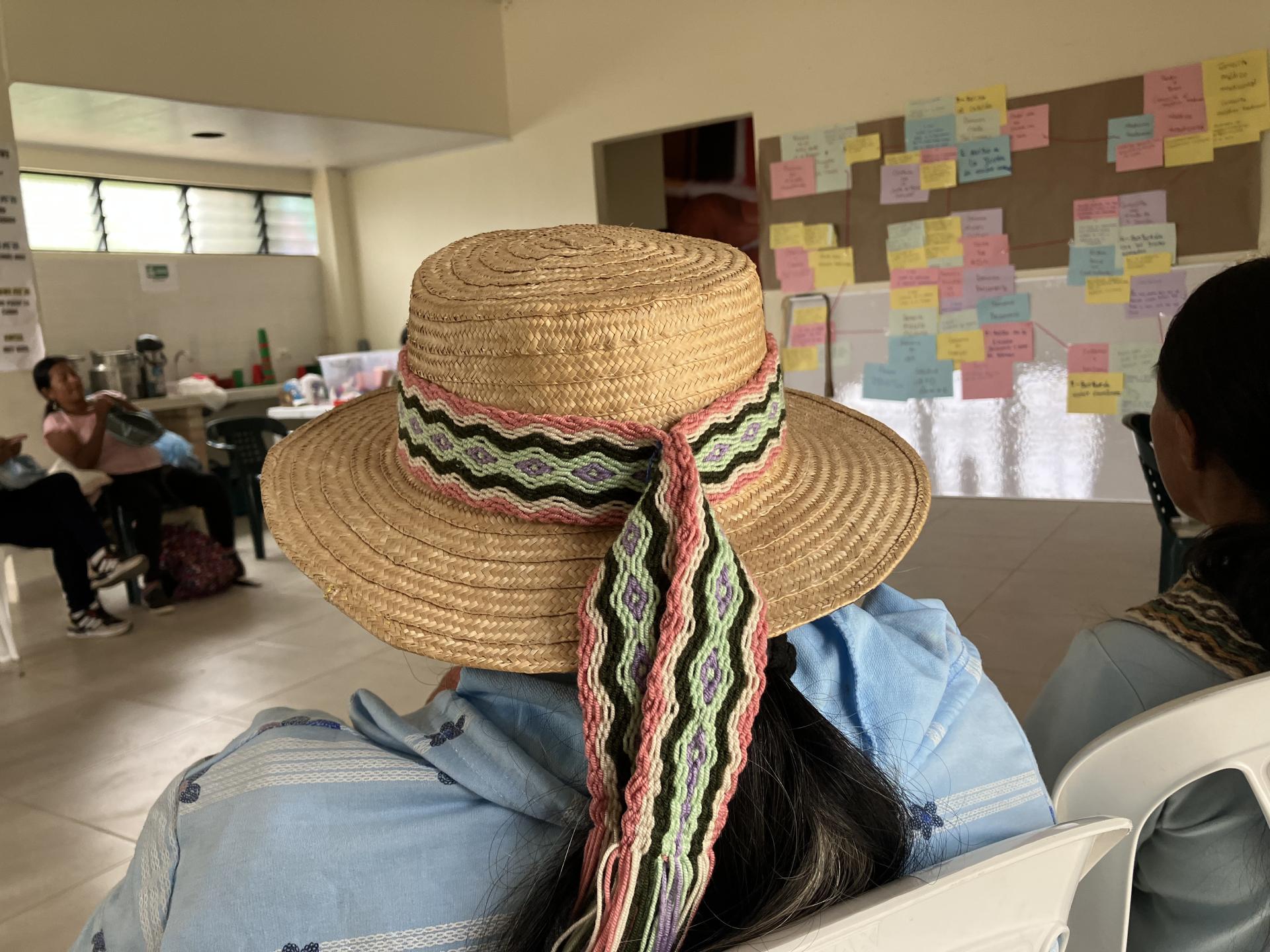

In this context, the group known in the Nasayuwe language as “U’ywe’sx Çxhaçxha Yaakxsaa” (Brave Women) emerged, finding a place to unite their voices at the House of Memory in Caldono, in Cauca. These 20 Indigenous women are searching for their relatives who disappeared during the armed conflict. Most are mothers who work and live off the land, weavers, and bilingual speakers of Nasayuwe. Within the group are women who have served as community leaders, and some are even signatories to the peace accords.

One of the group's voices is Carmen Rosa. Her leadership and strength have inspired other women to speak out more openly, in both Spanish and Nasayuwe, because they see in her a source of loving companionship and strength to counteract their fear. Like the other women in the group, Carmen is committed to the task of bringing her brother back. She resists not knowing the truth, but above all, the pain of not being able to reunite her family. When we asked her about the most challenging aspect of being part of the women searchers, she told us: “The hardest part of the search is not having the information for sure. Because we might be told that he was 'killed' or that he's somewhere, but we don't have the coordinates, so it's an unfinished process, part of the story. The hardest part is not knowing the location. So many years have passed since that happened; in my brother's case, 13 years.” Like many of the women of U’ywe’sx Çxhaçxha Yaakxsaa, Carmen has searched, walked, asked questions, challenged, and protested, unsettling an institutional framework that is often rigid in its approach to the search: “My brother had a spirit of disability, despite his height and the fact that he appeared to be an adult; in the end, he was like a 3- or 4-year-old child. No one in the government, nor the psychologists, can understand, because it is part of Indigenous spirituality, and only Indigenous people and those with wisdom can understand.”

One of the first collective actions of U’ywe’sx Çxhaçxha Yaakxsaa was a formal request to various institutions, written in both Spanish and Nasayuwe, to expedite the humanitarian search for their loved ones. This collective manifesto, woven together by many voices, demanded their rights and was accompanied by an audio recording in their native language for those women who have reading difficulties. In their collective letter, they stated:

“We recently came together to support and accompany one another in the long process of learning the whereabouts of our loved ones. We are daughters, sisters, wives, women searchers who continue fighting, some for decades, to find our family members. We came together to remember them, to honor their memory, to share our feelings, to advance the search collectively, and to demand our rights as women searchers from the institutions.”

Among their demands is the acceleration of search processes in their territories, taking into account the decades of searching and the State's silence. They also demand the recovery of unidentified bodies in their territory, as someone might find their loved ones there. Furthermore, they have demanded participation and training, as they are prepared to “pick up shovels and walk for hours” to locate their missing relatives.

The Collective Threads of Indigenous Women Searchers

The search in Indigenous territories has gained increasing strength, with women rising up to demand and propose solutions. From spirituality, customs, and self-governance, Indigenous women have traversed every inch of the territory, hoping to find answers among mountains silenced by conflict. Guardians of memory and builders of peace, these Indigenous women searchers are uniting to support one another, both emotionally and through the bureaucratic labyrinths of institutional searches. U’ywe’sx Çxhaçxha Yaakxsaa has established four interwoven threads of work rooted in the collective memories that emerge during these gatherings: Humanitarian Searching, Weaving, Plants, and Self-Care.

The first thread, at the center, is the search itself, where they share strategies with other groups of women searching for their missing loved ones, educate others, gather information, and advocate with institutions, because their objective is clear: “to keep searching until we find them and to support others.” Carmen Rosa explains that neither her search nor that of her companions has been easy due to all the discrimination and rejection they have suffered for being Indigenous. In her words, being Indigenous from Cauca in Colombia is viewed with suspicion: “We Indigenous people are often shunned in public places, like government offices. And there is discrimination simply for being Indigenous, it doesn't matter if we are old, young, male, or female, you go to the city, and they immediately label you a guerrilla, and even worse if they say you come from Cauca.” Indigenous women have had to confront even these barriers to demand their rights, facing different State entities that are supposed to search for their missing loved ones or provide them with assistance as victims of the armed conflict. One of the calls made by Indigenous women searchers is for respect for their worldview from those in charge of the search: “If there were someone with understanding, like an ancestral elder, the search could be easier, because with the searches, with the spiritual aspect, with the harmonization, with the offerings, one could find the family member very quickly.”

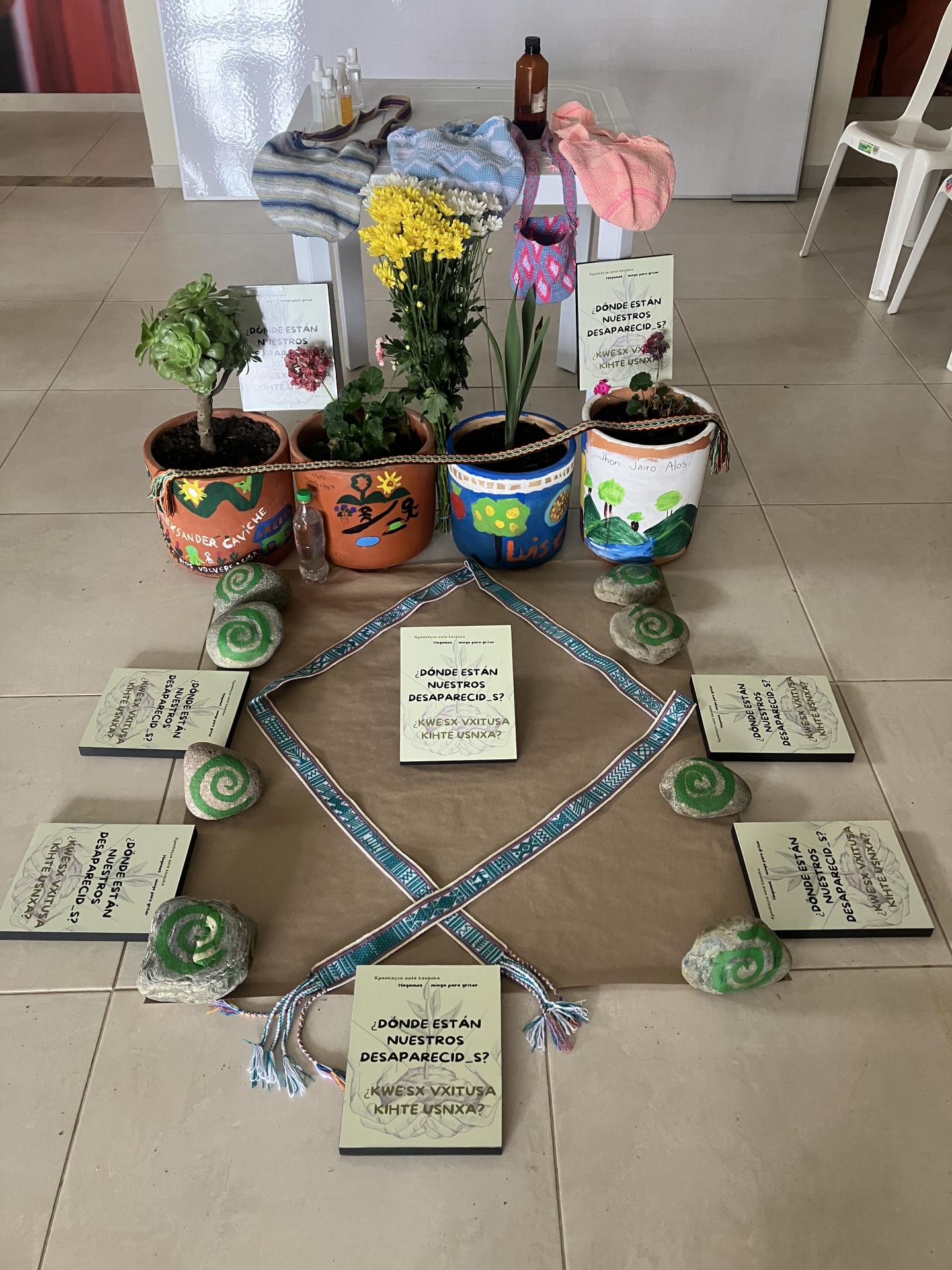

Weaving, as the second component, is the link that the women create between memory and territory. Jigras, bags woven with cabuya fiber, are the object that represents the connection to the maternal navel that nourishes and connects them to their loved ones and to the community. During each gathering, the women weave incessantly, interweaving threads and conversations, later sharing their backpacks or chumbes, a woven belt used by Indigenous mothers to carry their children, with the others.

Plants have accompanied each Indigenous woman's search in diverse ways. Some have turned to traditional medicine to learn about their missing loved ones, others to herbal infusions to soothe their anguish or as sources of protection. For this reason, the women of U’ywe’sx Çxhaçxha Yaakxsaa decided to decorate flowerpots where they planted various plants chosen for their spiritual and emotional significance. They are also planning a Garden of Remembrance to remember their family members and to harvest the plants that aid in their searches. A few months ago, they decided to go on a minga (collective work) to the Ovejas River to collect stones for the Garden. Carrying the stones symbolized the search itself, an exhausting task where the weight of the disappearance is felt, a weight that has been lightened by sharing it with others.

Finally, but no less importantly, these women searchers from Caldono have chosen to strengthen self-care and co-care. As Nasa women, they care for the territory and the community, extending their family to them. They care for the crops and community assemblies, they care for the language and traditions. They are caretakers of the collective, one that remains wounded by the void of disappearance, absences that affect the harmony of the territory and community life plans. “We have learned to carry this pain together,” say the women of U’ywe’sx Çxhaçxha Yaakxsaa. Therefore, caring for themselves and their fellow searchers is a political act, finding in this process a space to cry, laugh, receive massages, relax, rest, and share. Currently, these women are building self-care bags, where each woman will carry essential oils, medicinal plants, mineral salts, and other items for her own care.

The women searching for U’ywe’sx Çxhaçxha Yaakxsaa will continue to meet on Saturdays to support one another, advocate for humanitarian search efforts, share their struggles, and care for each other collectively. Like Carmen Rosa, these women of the Nasa people refuse to accept the pain of disappearance; they want to find the truth and locate their loved ones to heal the wounds left by violence.