As the Arabian Peninsula continues its ascendance as a global hub for the arts—marked by an ever-expanding array of world-class museums, cultural institutions, and performance venues, with festivals and art fairs abounding throughout—the Emirate of Sharjah, U.A.E., leads the way in celebrating Indigenous contemporary art and artists. The 2025 “Sharjah Biennial 16: to carry” featured more than 40 such artists (out of over 190 total) from every continent and across five distinct curatorial programs; the majority presented in that of Megan Tamati-Quennell (Ātiawa, Ngāti Mutunga, Kāti Māmoe, Ngāi Tahu, Waitaha), a preeminent curator and scholar of Māori and (other) Indigenous contemporary art for more than 35 years. Cristina Verán recently spoke with Tamati-Quennell about this special collaboration and more.

Cristina Verán: Your career is marked by visionary leadership that continues to steward, galvanize, and elevate the continued rise of Indigenous contemporary art and artists, both in Aotearoa/New Zealand and internationally. How did this bring you to Sharjah?

Megan Tamati: This story goes back to London in 2018, when a major exhibition, “Oceania,” was presented at the Royal Academy of Art. It was a show of taonga—“cultural treasures” along with some contemporary art from New Zealand and the Pacific. Curators Nicholas Thomas and Peter Brunt included a special work in it that I had bought for the collection at Te Papa Museum in New Zealand, an iconic work: a fully carved red Steinway concert grand piano by Māori artist Michael Parekōwhai “He Kōrero Pūrakau mo Te Awanui o Te Motu: Story of a New Zealand River”—a Duchampian [made-over readymade] work that Parekowhai had first made for his Venice Biennial exhibition "On First Looking in Chapman’s Homer" in 2011. I delivered a paper about it for London’s Royal Academy of Art and, from that, Tim Marlow, the director, invited me to speak at a cultural summit that he was organizing in Abu Dhabi the following year. It was there that I first met Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, President of the Sharjah Art Foundation.

She invited me then to the Emirates—for my first time—to attend Sharjah Biennial 14: Leaving the Echo Chamber (curated by Zoe Butt, Omar Kholeif, and Clair Tancons) in 2019. A few years later—delayed because of COVID— Sheikha Hoor asked me to speak at the Sharjah Foundation’s Annual March Meeting; a lead-up to Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present, in 2023.

Megan Tamati-Quennell. Image courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation. Photo by Danko Stjepanovic.

CV: Did she have some familiarity with and interest in Māori art at the time?

MTQ: Yes. She mentioned wanting to bring two Māori artists, Robin Kahukiwa (Ngāti Porou/ Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti/ Ngāti Kōnohi/ Te Whānau-a-Ruataupare/ Ngāti Porou) and Kahurangiariki Smith (Te Arawa/ Rongowhakaata/ Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki) for the next Sharjah Biennial, and asked if I could connect her with them.

Some time after, Hoor reached out again to say that she was going to Sydney and would like to stop over in New Zealand. Happily, I organized an itinerary and did studio visits with her up and down the country. She fell in love with the work of Emily Karaka (Ngāti Tai ki Tāmaki/ Ngati Hine/ Ngāpuhi), an artist who, in a career spanning 60 years or so, had never had a major solo exhibition or a survey show. Hoor proposed that we do a project together focused on Emily’s art and her practice; an extraordinary opportunity. We got on very well, and when I mentioned that there were certain things I’d really been wanting to do but couldn’t, as a curator in New Zealand, Hoor offered me the platform to do them for the Biennial 16; an exciting opportunity.

"Untitled (25° 21' 11.1" N 55° 24' 43.9" E)" by Australian artist Daniel Boyd (Kudjala, Ghungalu, Wangerriburra, Wakka Wakka, Gubbi Gubbi, Kuku Yalanji, Bundjalung, Yuggera, Ni-Vanuatu).

CV: How did your vision for this come together, and what would you describe as a central thread connecting all of its parts to the eventual whole?

MTQ: I wanted something that would speak to the commonalities found across all of humanity, but especially those shared by Indigenous Peoples—such as being in relationship with land and place, over time. For most of the artists, Sharjah was far from home, and many had limited experience of the region where Sharjah is located. Key questions I asked, of myself and of the others then in the planning, included: What are one’s responsibilities while in somebody else’s country or land, as a visitor? How could these works, made by artists from abroad, ground themselves in the local? What might the commonalities or cross-cultural solidarities be between these artists and the people, cultures, land, and location of Sharjah given that they all represent primarily non-western communities? How does this land affect and inform how we operate?

“Veritas” by Kaili Chun (Kanaka ‘Ōiwi, Hawai’i).

CV: By what criteria did you consider and ultimately finalize who, what, and from where to include?

MTQ: There were many approaches and a lot of research and thought involved. What it came down to was working with artists whose work and practice I was interested in; those with whom I felt some kind of synergy—conceptually, intellectually, and/or aesthetically—and that could respond to the proposition for the project I wanted to develop. I also thought about what I could offer to the context I was working in; what could I bring to Sharjah? And within that, I felt I had to be true to myself, as a curator. And also, it was important to me to also to bring to Sharjah artists and work from the Asia Pacific region, where I live and work.

With some of these artists and their respective practices, I already had a long-term relationship —a few for 30 years or more. Others, I hadn’t yet w orked with before, but had always wanted to; artists I had always admired and for whom I have had a deep respect for. There were also those that I met through the curatorial research process, and with whom I had never worked with before. My project also endeavored to include some artists who had not shown their work in biennials before.

CV: How did you envision these factors would help to shape the audience’s experience in Sharjah?

MTQ: I thought about the individual works it in terms of how they would operate spatially, experientially, and conceptually in particular spaces. Also, I considered how the overall curatorial project could be read across multiple locations and venues; what ideas or messages would it carry. What was the essence of the project I was attempting to realize? How would it sit among the projects of my co-curators, with whom I was often sharing venues, even as they were perhaps working with different sets of ideas, approaches, and/ or activations than my own?

"Ihi: Awa Herea: Braided Rivers," featuring vocalist Mere Tokorahi Boynton (Te Aitanga a Mahāki, Ngāti Oneone, Ngāi Tūhoe), with pianist Liam Wooding (Te Atihaunui a Pāpārangi, Ngāti Tuera, and Ngāti Hinearo) playing the famed red piano "He Kōrero Pūrakau mo Te Awanui o Te Motu: Story of a New Zealand River," by Michael Parekōwhai (Ngāriki Rotoawe, Ngāti Whakarongo).

CV: Going back to the land/ place connections you’ve noted, please share some examples where such connections were most apparent and meaningful—and what inspired your linking of specific artists and places together.

MTQ: I chose to present the work of Indigenous Australian artist Daniel Boyd (Kudjala/ Ghungalu/ Wangerriburra/ Wakka Wakka/Gubbi Gubbi/ Kuku Yalanji/ Bundjalung/ Yuggera/ Ni-Vanuatu) in a building that’s known in Sharjah as the "Flying Saucer" because I was interested not only in his paintings, but his architectural interventions, both conceptually and spatially, critiquing different knowledge systems. I paired him there with musician Mara TK (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Kahungunu, Tainui) whose sound installation “Ngā Mata ō Hina,” based on a Māori lunar calendar, in a nod also to the significance of the lunar calendar for Islamic cultures. This made their project into an experience the audience could enter and be enveloped by.

Then, an artist who has long interested me, Raven Chacón (Diné)—whose practice includes composition and sound as well as installation, photography, video, and other forms— created a new sound work with local Bedouin musicians at Al-Madam, also known as the Ghost Village—a site he said that he once dreamed about. It’s an abandoned former housing project created in the early 1970s for a local BedouinTribe during the time when the U.A.E. unified, who abandoned it to return to their traditional, more transient and mobile ways, leaving the houses to, over time, fill with sand. This idea of what Raven called "forced placement,” paralleled his own community’s experience in the U.S. with government-imposed housing— in which his family chose not to live in either. This sound installation, in effect, returned the people to that village as their song moved through it, before ultimately returning itself to the desert environment to which they belong.

“Operation Buffalo” by Yhonnie Scarce (Kokata/ Nukunu, Australia).

CV: What are some further highlights of your Sharjah program worth special note, perhaps?

MTQ: There are so many I could speak to, really. For one, the works of Indigenous Australian artist Yhonnie Scarce (Kokatha, Nukunu)—one of the first I thought about for this Biennial—addressed the theme of nuclear colonization in Australia and, in particular, the testing of nuclear bombs by the British in South Australia during the 1950s and 60s with Australian government support. Her installation “Operation Buffalo”, which was made for the Biennial and shown in Hamriyah, also had a relationship to Sharjah and its desert environment, in terms of materiality: sand, silica, and glass.

A pre-existing work of hers, “Orford Ness,” was shown at the Kalba Ice Factory site alongside paintings by Diné artist, Steven Yazzie, about the constantly changing, never-ending movement of the land he grew up on within the Navajo Nation; both of them creating "refracted landscapes."

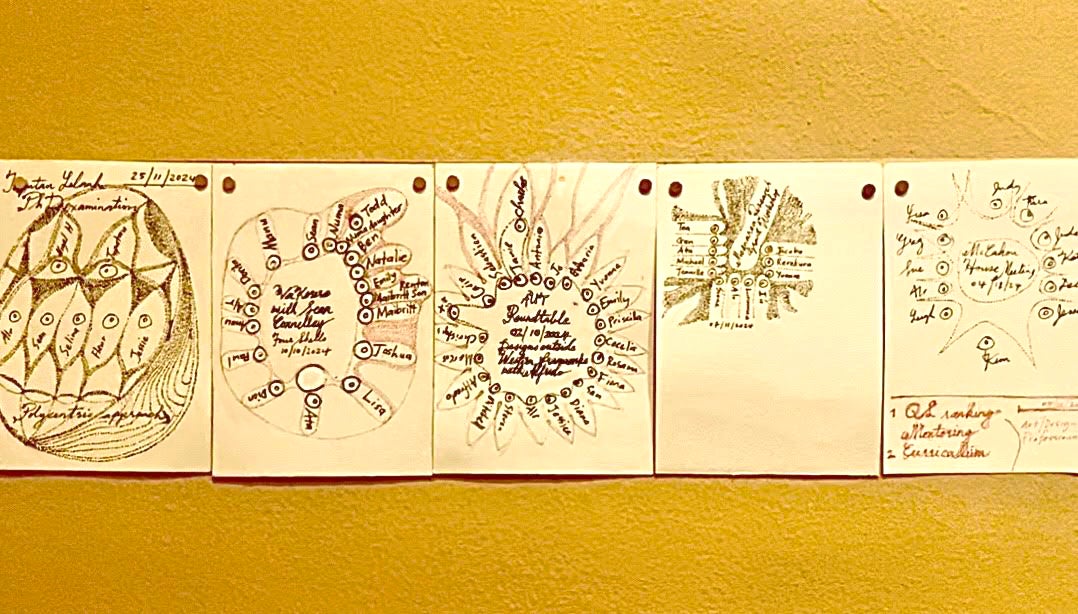

There’s the photography of Māori artist Fiona Pardington (Ngāi Tahu/ Kāti Māmoe/ Ngāti Kahungunu) as well, that presents images of life casts created in the 1820s of three Ngāi Tahu tupuna, or ancestors, that recall a proto or pre-photographic form of portraiture. And then there’s installation “Purapura Whetū” by Saffron Te Ratana (Ngāi Tūhoe), “Whakamoemoeā,” a film that I commissioned from Fijian artist Luke Willis Thompson (Fiji/New Zealand), and the amazing photographs by Kapulani Landgraf (Kanaka Maoli/ Hawai’i) of what she describes as "ancestral storied landscapes" of Maui, kind of transported this island here to the desert of Sharjah. I should also mention Albert Refiti (Samoan), a New Zealand-based academic and architect, whose installation “Vānimonimo” comprised an entire room filled with his extraordinary drawings with hundreds of little notations – what he calls “field notes” - that mark gatherings of people and ceremonies. Each was articulated and manifested through a whole knowledge system to do with the vā, which, in Samoan culture, refers to sacred space and maps relationships, both spatial and relational, between things and also between people.

"From 'Āhua: a beautiful hesitation" by Fiona Pardington (Ngāi Tahu, Kāti Mamoe, Ngāti Kahungunu).

CV: The closing for the Biennial’s “April Acts” program featured an exquisitely ethereal music performance, “Ihi: Awa Herea (Braided Rivers).” How did it all come together?

MTQ: I really wanted to do something special with Michael Parekowhai’s [aforementioned] piano, and so I thought about working with opera singer Mere Boynton (Te Aitanga a Mahāki/ Ngāti Oneone/ Ngāi Tūhoe), an extraordinary Māori soprano, whom I have known for years, and Māori concert pianist Liam Wooding (Te Atihaunui a Pāpārangi, Ngāti Tuera and Ngāti Hinearo), who had approached me a number of years ago about playing He Kōrero—a work artist Parekowhai intends to be played in order to activate it, with audience engagement. I thought about bringing them together with the piece, to create a performance here in Sharjah.

The three of us had several collaborative Zoom meetings to work through ideas, including the use of both Māori and European music; songs both classical and contemporary, with the idea of braiding cultures together. The program takes its title from a composition called "Awa Herea," by Gillian Whitehead, a leading New Zealand Composer.

With that, I thought it was important to bring together these two Māori performers and allow the iconic He Kōrero to have the last word, so to speak.

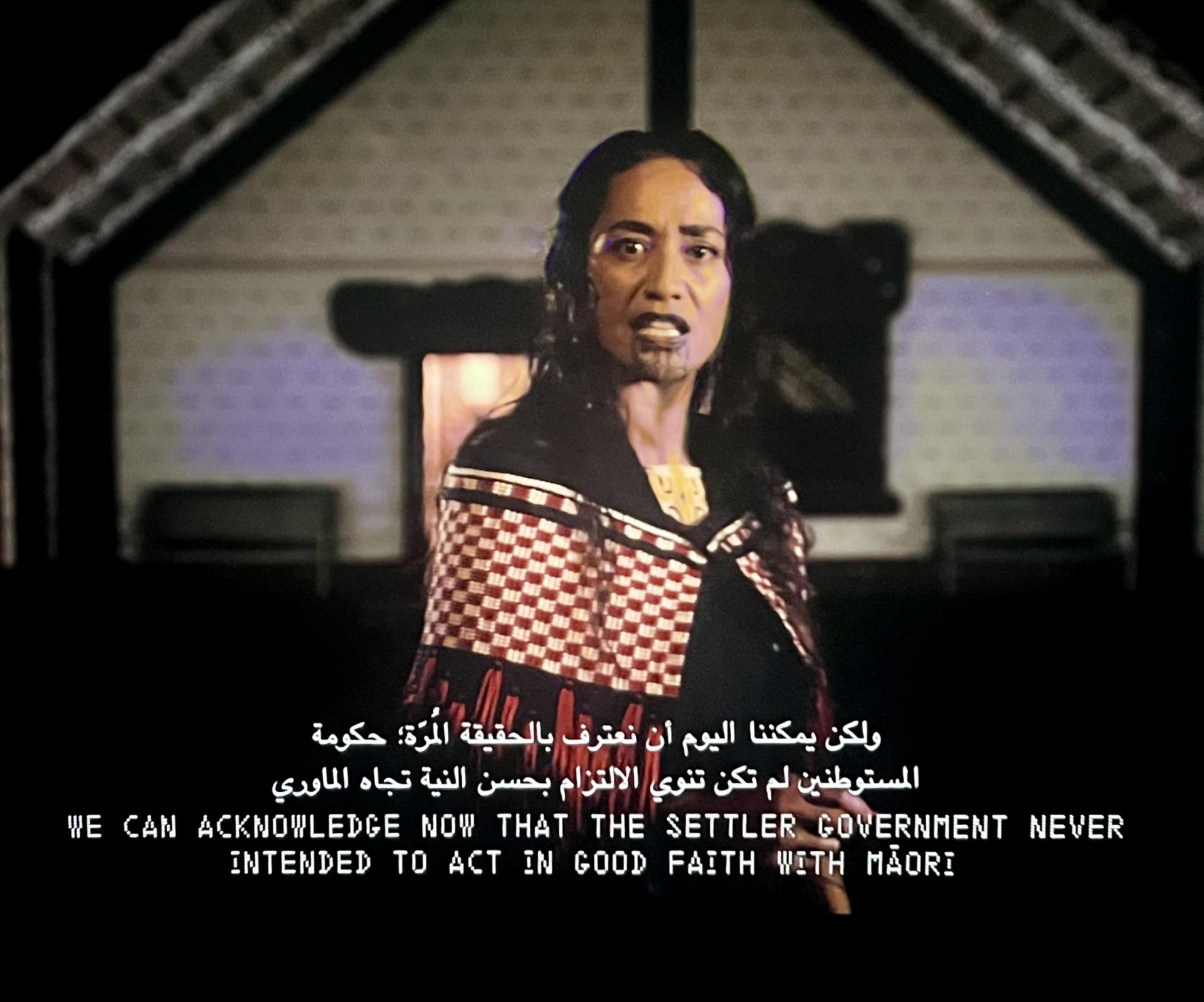

"Whakamoemoeā" by Luke Willis Thompson (Fiji/ New Zealand).

“Te Ao Hurihuri” by Michael Parekōwhai (Ngāriki Rotoawe/ Ngāti Whakarongo, Aotearoa).

"Whispers Midden" by Australian artist Megan Cope (Quandamooka).

“Vānimonimo,” by Samoan scholar and architect Albert Refiti.

--Cristina Verán is an international Indigenous Peoples-focused specialist researcher, educator, advocacy strategist, network weaver, and mediamaker. As adjunct faculty at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, she brings emphasis to the global histories, movements, innovations, and socio-political impacts of Indigenous contemporary visual and performing arts.

Top photo: “Purapura Whetū” by Saffronn Te Ratana (Ngāi Tūhoe, Aotearoa).