El gobierno y la industria harán lo que sea necesario para sacar adelante los proyectos mineros, pero la oposición Indígena es fuerte en el corazón de los Andes.

Por Brandi Morin (cree/iroquesa/francesa). Fotos por Ian Willms

En esta serie, hemos intentado contar las historias de los Pueblos Indígenas que resisten, en gran medida solos, frente a las fuerzas del gobierno y la industria. Han encontrado apoyo para sus reclamos en equipos legales internacionales, organizaciones como Amnistía Internacional, ramas de las Naciones Unidas y la asociación Indígena más grande de Ecuador. Como sucede en todo el mundo con la minería, muchas de estas empresas son canadienses —y, sin embargo, los abusos y excesos de la industria minera global rara vez se mencionan en Canadá.

Pero hay personas a nivel local que apoyan los proyectos mineros y los empleos que estos generan. Al regresar a Canadá, recibimos una serie de correos electrónicos de un gerente local de Atico Mining insistiendo en que volviéramos y nos reuniéramos con un grupo seleccionado de simpatizantes. A lo largo de decenas de páginas, caracterizó la resistencia al proyecto de Atico como orquestada por “grupos antimineros violentos” apoyados por “plataformas políticas y crimen organizado transnacional”.

Sus afirmaciones, como leerás en las siguientes páginas, en gran parte contradicen lo que escuchamos de las fuentes que entrevistamos. Y un viaje de regreso para asistir a una reunión tan escenificada es tanto logísticamente complicado como éticamente cuestionable.

Pero su desesperación por organizar eventos mediáticos que muestren apoyo local al proyecto minero revela cuán importante es para la empresa y para aquellos habitantes locales cuyos empleos o medios de vida dependen de su realización.

"Sintiendo impotencia"

Desde su oficina en Palo Quemado, donde se lleva a cabo otra ronda de consultas organizada por el Ministerio de Ambiente justo al lado, Gabriela Guarachico habla con el peso de una comunidad dividida sobre sus hombros. Con solo 32 años, la joven presidenta del GAD (Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado) de la parroquia Palo Quemado se encuentra en el centro de un conflicto minero que ha desgarrado el tejido social de su tradicionalmente pacífico pueblo.

“Antes de todo esto, los niños de Las Pampas venían aquí a jugar deportes. Solíamos compartir actividades entre comunidades,” dice, ajustando su gorra negra, con su coleta oscura visible debajo. “Pero desde que comenzó este proceso, todo cambió. Ese lazo social se rompió. Ahora hay desconfianza. Ya no visitan Palo Quemado.”

La presencia de fuerzas militares en su antes tranquila parroquia le resulta especialmente preocupante.

“Ver tantos policías te incomoda. Ya no puedes hacer tus actividades diarias como antes,” explica, con su vestimenta informal contrastando con la gravedad de sus palabras. “Palo Quemado siempre se ha caracterizado por ser una parroquia tranquila. Esto nunca había pasado".

Describe una comunidad fracturada en tres grupos: los que apoyan la mina, los que están en contra y los que permanecen en silencio. Como su líder, se encuentra en una posición imposible. “Como autoridad, te sientes impotente,” admite. “Tienes las manos atadas. No podemos ir en contra del gobierno nacional.”

Lo que más le frustra es que, a pesar de que Palo Quemado está a solo tres kilómetros del sitio minero —lo suficientemente cerca como para ver el futuro campamento desde el pueblo—, no se les considera dentro de la zona de impacto directo. “Hemos luchado para que toda la población de Palo Quemado sea considerada como un área de influencia directa. El ruido de los vehículos que van a pasar por aquí, el polvo, todo ese tipo de cosas —nos afectarán también. Pero, lamentablemente, los técnicos solo consideraron dos ubicaciones.”

Mirando hacia la cordillera donde ahora letreros de propiedad privada marcan el territorio de la empresa minera, expresa el temor más profundo de la comunidad: “Hablan de remediación en sus documentos, de cómo van a reforestar, pero el suelo no será el mismo. Y el agua —no tenemos agua en abundancia aquí. Esa es la preocupación”.

El CEO de Atico culpa a "manifestantes antimineros violentos"

La naturaleza forzada del proceso de consulta es evidente —diseñada no para escuchar, sino para legitimar. Guardias armados están en posición, supuestamente para proteger contra manifestantes “violentos”, aunque la única violencia que muchos aquí han conocido vino de las fuerzas del gobierno durante protestas pacíficas.

El CEO de Atico Mining, Alain Bureau, hablando desde su oficina en Quito vía Zoom y rodeado de mapas del proyecto La Plata y afiches promocionales, cuenta una versión dramáticamente distinta del conflicto.

“La comunidad de Palo Quemado invitó a la policía,” insiste, afirmando que aproximadamente 100 residentes dentro de la zona afectada solicitaron protección militar contra “grupos violentos” provenientes de Las Pampas y otras zonas.

Bureau va más allá, sugiriendo que hay elementos criminales involucrados: “El mayor desafío en este momento es el crimen organizado. El crimen organizado no quiere la formalización de las zonas”.

La empresa afirma que se han descubierto operaciones de minería ilegal en Las Pampas, insinuando vínculos entre defensores del medio ambiente y redes criminales —acusaciones que los miembros de la comunidad niegan rotundamente.

Manifestantes etiquetados como ‘agitadores externos’ por el CEO de la minera

Desde su oficina en Quito, apareciendo profesional y serena a través de Zoom, María Silva, presidenta ejecutiva de la Cámara de Minería del Ecuador, también presenta un fuerte contraste con la violenta realidad que se vive en Las Pampas y Palo Quemado. Su voz se mantiene firme mientras defiende la postura de la industria minera, enfatizando repetidamente su compromiso con los “estándares” y la “minería responsable”.

“Primero que todo, me gustaría entender o precisar qué supuestas violaciones a los derechos humanos han ocurrido,” dice, con un tono que minimiza la violencia documentada. Al ser presionada sobre el incidente de marzo de 2024, cuando se desplegaron fuerzas militares y Mesías recibió un disparo que lo dejó en coma durante tres meses, cambia el enfoque hacia justificaciones legales.

“No ha habido criminalización de las protestas”, insiste, a pesar de la evidencia que indica lo contrario. “Los hechos ocurridos en los meses anteriores involucran actos graves de violencia perpetrados por personas ajenas a las comunidades afectadas.” Caracteriza a los residentes de Las Pampas como agitadores externos, a pesar de su cercanía a la mina.

Al ser confrontada directamente sobre el caso de Mesías, Silva se desvía. “Nuestra respuesta es la que ya le indiqué,” dice con frialdad. “Este proceso se ha llevado a cabo pacíficamente, en las comunidades que fueron identificadas por los estudios antropológicos como comunidades de influencia directa del proyecto”.

Silva recurre repetidamente a un lenguaje técnico sobre los procesos de consulta y fallos de la Corte Constitucional, evitando cualquier reconocimiento del costo humano. “La consulta no la realiza la empresa, la realiza el Estado ecuatoriano”, insiste, desvinculando a la empresa minera de cualquier responsabilidad.

Su fondo en Zoom muestra una oficina impecable, a mundos de distancia del gas lacrimógeno y las balas que enfrentaron los residentes de Las Pampas. “Honestamente queremos promover nuestra industria con los mejores estándares disponibles”, concluye.

La violencia contra los miembros de la comunidad que se oponen a la mina ha generado condena internacional. La Relatora Especial de la ONU sobre Defensores de Derechos Humanos, Mary Lawlor, expresó su preocupación por los “riesgos para los defensores de derechos humanos” en las comunidades, mientras que Amnistía Internacional denunció el “uso excesivo de la fuerza” por parte de las fuerzas de seguridad, señalando que “la munición real está prohibida como medio para disolver protestas”.

La abogada Alejandra Zambrano Torres dijo a Ricochet que el Decreto 754 resume el enfoque del gobierno: “El proceso de consulta se ha convertido en un simple trámite para autorizar la minería, impuesto bajo condiciones de militarización, intimidación y violencia policial. Cuando se deja en manos de los propios reguladores del proyecto, la participación suele ser restringida".

Señala que el decreto contradice tanto la Constitución de Ecuador como los estándares internacionales de consentimiento libre, previo e informado.

Mientras tanto, Bureau presenta una imagen de un proyecto que traería prosperidad a través de empleos y desarrollo. “Vamos a tratar de formalizar toda la zona,” dice, describiendo planes de programas de formación y empleo de calidad. “Nuestros proveedores podrían ser la tienda de la esquina, el señor que nos alquila su camioneta —tendrán que formalizarse, tener una cuenta bancaria, saber cómo manejar sus cosas, pagar sus impuestos. Eso va a cambiar toda la región".

Sin embargo, Juan Carlos Carvajal Silva (ver parte tres) cuestiona varias afirmaciones clave hechas por la empresa minera. “Es una cosa hablar desde otro país, y otra muy distinta venir al territorio y conocer realmente la realidad,” dice Carvajal Silva, destacando la desconexión entre las presentaciones corporativas y las experiencias locales.

Él desafía directamente la caracterización que hace Atico de la zona de impacto del proyecto, explicando que, aunque la empresa solo reconoce a dos comunidades —Las Minas y San Pablo— como dentro de la zona de impacto, la huella real del proyecto abarca 2.230 hectáreas, afectando a muchas más comunidades. Cree que las comunidades dentro del alcance geográfico del proyecto están siendo sistemáticamente excluidas, a pesar de su proximidad a las operaciones mineras y los posibles impactos en sus medios de vida.

Las apuestas son especialmente altas para la comunidad de Las Pampas, donde más del 80% de los productores locales exportan productos orgánicos a mercados internacionales, incluyendo Italia, España, Estados Unidos y, paradójicamente, Canadá —el país de origen de Atico Mining.

“Somos productores de caña de azúcar orgánica. Con una empresa minera al lado, con tanta contaminación que ellos mismos aceptan que van a producir… vamos a perder las siete certificaciones orgánicas que tenemos, y no queremos eso”, explica.

Las preocupaciones por el agua están en el centro de la oposición local. El plan de la empresa para extraer 46 litros de agua por segundo genera alarma en una región que ya sufre escasez hídrica. Carvajal Silva enfatiza que las operaciones mineras subterráneas afectarán las fuentes de agua subterránea de las que dependen las comunidades locales, señalando que Palo Quemado ya “no tiene agua” debido a la sequía y la extracción hidroeléctrica.

En respuesta a las acusaciones de violencia por parte de grupos antimineros, Carvajal Silva ofrece una refutación: “La violencia es un juego del gobierno, que provoca la violencia. El gobierno, bajo un decreto inconstitucional, militariza Palo Quemado. Nosotros simplemente defendemos nuestros territorios”.

Presenta la resistencia local no como agresión, sino como defensa de recursos fundamentales: “Si defender el agua es violencia, frente al extractivismo que viene de manera voraz… defender el agua es defender la propia vida”.

‘Volando cada ángulo de la montaña’

Bajo las cumbres amenazadas dentro del área de concesión de la mina, los planes de Atico revelan una agresiva red de túneles diseñada para penetrar cada ángulo de la montaña donde puedan encontrarse minerales. Los ingenieros de la empresa han trazado una estrategia de extracción implacable, empleando tres métodos distintos para perseguir el mineral a donde sea que se encuentre, sin importar la estructura natural de la montaña.

En las secciones más empinadas, donde el mineral corre casi verticalmente, volarán enormes cámaras utilizando el método de ‘bench-and-fill’ (bancada y relleno), dejando vacíos enormes que luego serán rellenados con roca de desecho. Donde el cuerpo mineral se retuerce y debilita, cambiarán al método de ‘cut-and-fill’ (corte y relleno), abriéndose paso capa por capa. Incluso en las zonas más planas, seguirán el mineral con el método ‘drift-and-fill’ (galería y relleno), asegurándose de que ninguna sección rentable quede sin explotar.

La escala de maquinaria planificada para esta operación es colosal: jumbos electrohidráulicos perforarán el frente rocoso, mientras unidades de carga de diez toneladas recogerán el mineral roto. Camiones de veinticinco toneladas retumbarán a través de los túneles día y noche, transportando mineral y roca de desecho hacia los acopios en la superficie —acopios que los habitantes temen que filtren contaminación a sus fuentes de agua durante la temporada de lluvias.

Sus planes de voladuras contemplan una mezcla de explosivos ANFO y emulsiones, lo suficientemente potentes como para fracturar secciones de montaña de entre cuatro y ocho metros de espesor. Aunque la empresa afirma que este enfoque minimiza el daño a la roca circundante, los miembros de la comunidad se preocupan por el impacto de las explosiones constantes sobre la estabilidad de la montaña y sus fuentes hídricas.

Cada método de extracción ha sido elegido para maximizar la eficiencia, transformando la montaña viva en un laberinto de túneles y cavidades rellenas.

A nivel global, Canadá es un actor dominante en la industria minera. Toronto sirve como epicentro internacional de financiamiento minero, con bolsas de valores que albergan más del 70% de las compañías mineras del mundo. Esta influencia desproporcionada moldea la extracción de recursos en América Latina, donde las empresas canadienses operan bajo un marco regulatorio que, según los críticos, prioriza las ganancias sobre los derechos humanos y la protección ambiental. A pesar de las directrices del gobierno canadiense como “Voces en Riesgo” para apoyar a defensores de derechos humanos, y su tan promocionada estrategia de Conducta Empresarial Responsable, las empresas mineras enfrentan pocas consecuencias significativas en su país por sus acciones en el extranjero.

El giro de Ecuador hacia la minería ejemplifica el alcance de la influencia canadiense. Después de décadas dependiendo principalmente del petróleo, el gobierno ecuatoriano ahora promueve la minería como clave para el desarrollo económico, con empresas canadienses liderando el camino. En la conferencia de 2024 de la Asociación de Prospectores y Desarrolladores de Canadá (PDAC), el presidente Daniel Noboa presentó a Ecuador como “el próximo destino minero”, prometiendo permisos simplificados y mayores protecciones para la inversión. Esto marca un giro drástico respecto a la constitución de 2008 de Ecuador, que consagraba los derechos de la naturaleza y exigía consulta previa a los Pueblos Indígenas sobre proyectos extractivos.

El gobierno canadiense facilita activamente esta expansión a través de diversos mecanismos: Export Development Canada proporciona financiamiento y seguros a las empresas mineras, las embajadas canadienses ofrecen apoyo político, y los comisionados de comercio ayudan a las empresas mineras a navegar la normativa local. Mientras tanto, los intentos de establecer una supervisión más estricta —como el fallido proyecto de ley C-300, que habría creado mecanismos de rendición de cuentas para las empresas extractivas canadienses que operan en el extranjero— han sido derrotados por la presión de la industria.

Esta dinámica se repite en todo Ecuador a través de una secuencia de eventos ya conocida: se otorgan concesiones mineras sin la debida consulta, las comunidades que resisten enfrentan criminalización y violencia estatal, y las misiones diplomáticas canadienses guardan un silencio notable sobre las violaciones a los derechos humanos mientras continúan promoviendo la inversión minera. El Decreto 754 y el despliegue de fuerzas militares para proteger los intereses mineros demuestran cómo las prioridades de inversión de Canadá pueden reconfigurar el aparato legal y de seguridad de un país.

Organizaciones internacionales de derechos humanos han señalado repetidamente este patrón, destacando cómo los intereses mineros canadienses contribuyen a la militarización de zonas rurales, a la criminalización de defensores ambientales y a la erosión de los derechos Indígenas. Sin embargo, tanto en Ottawa como en Quito, el enfoque sigue siendo expandir la frontera minera de Ecuador, con las empresas canadienses posicionadas como las principales beneficiarias de esta fiebre por los recursos.

Atico Mining ha incorporado algunas medidas de mitigación ambiental en sus planes. La empresa planea implementar sistemas de recolección de agua de lluvia y bombeo de agua superficial, pero el impacto a largo plazo sobre las cuencas hídricas locales sigue siendo una preocupación para los miembros de la comunidad. El compromiso de la empresa de usar un sistema de relaves secos apilados y filtrados para el almacenamiento de desechos representa un enfoque más moderno en comparación con las tradicionales piscinas de relaves húmedos, pero aún requiere monitoreo y gestión rigurosos.

El impacto del proyecto en la vida silvestre va más allá de la simple alteración del hábitat. El ruido de las operaciones diarias, el aumento de la actividad humana y la fragmentación del hábitat causada por la nueva infraestructura afectarán a la fauna local de formas que podrían no ser evidentes de inmediato. Esto es especialmente preocupante en Ecuador, donde los frágiles equilibrios ecológicos han evolucionado durante millones de años.

El consumo de energía representa otro desafío ambiental. Las demandas energéticas de la operación requieren nueva infraestructura, lo que contribuye a la huella de carbono general del proyecto. Aunque la empresa ha esbozado planes para la construcción de líneas eléctricas, los detalles sobre la integración de energías renovables o estrategias para reducir emisiones de carbono siguen siendo poco claros.

Sin embargo, varios aspectos cruciales no se han abordado en los anuncios públicos, incluyendo planes de monitoreo ambiental a largo plazo, medidas específicas para la protección de la biodiversidad y estrategias integrales de rehabilitación post-minería.

El proyecto ejemplifica la tensión constante entre el desarrollo económico y la protección ambiental, especialmente en países como Ecuador, donde los recursos naturales y los ecosistemas únicos coexisten.

‘Empresas canadienses que vienen a destruir en nombre de Canadá’

La luz del sol de la tarde proyecta largas sombras sobre el patio de la iglesia en Las Pampas, donde el padre Patricio Broncano cuida su querido jardín. Sus manos curtidas —las mismas que bendicen a su congregación y consuelan a los heridos— ajustan con delicadeza una planta florecida. A pesar de sus sienes encanecidas y las profundas arrugas alrededor de sus ojos que hablan tanto de risas como de dolor, hay una energía juvenil en sus movimientos. Sus gafas de montura negra reflejan la luz mientras se sienta sobre un tronco, rodeado de las coloridas flores que ha cultivado con el mismo cuidado que muestra por su comunidad.

El camino del padre Broncano hacia Las Pampas no fue directo. Nacido en las montañas de Pelileo, cerca de Baños, su familia se mudó a Latacunga en busca de mejores oportunidades. Antes de llegar a Las Pampas, pasó dos décadas en la Amazonía, dedicado a la evangelización.

“Vine aquí a descansar”, dice con una sonrisa amarga, “pero creo que no he podido.” Su voz se quiebra ligeramente mientras continúa: “Es contradictorio. Vine por ellos, porque vine a descansar con ellos”.

Sus ojos se pierden en la distancia mientras recuerda sus batallas anteriores. “Tuve algunos años de conflicto con los brocoleros allá en la sierra, empresas muy grandes, con las florícolas... Hubo muchas situaciones de abuso, como el uso de pesticidas y el abuso ecológico.” Niega con la cabeza. “Así que vine a descansar aquí, y me topé con la triste historia de que aquí estaban en un proceso de explotación minera”.

El dolor en su voz se profundiza cuando habla de amistades rotas. “Tengo amigos en Palo Quemado, bueno, tenía amigos. Por este tema se alejaron de mí y quienes fueron mis amigos desde muy jóvenes ya no quieren verme.” Sus manos se aprietan ligeramente sobre su regazo. “No tengo nada contra mi gente, contra mis amigos. [Mi enojo] es contra la empresa que vino a destruir esa amistad, esa familiaridad, y ha destruido los lazos familiares aquí en la provincia”.

Al hablar sobre las empresas mineras canadienses, su tono cambia del dolor a la rabia contenida. “Creo que el pueblo canadiense no sabe lo que está pasando aquí. Pero las empresas canadienses son las que vienen a destruir en nombre de Canadá.” Su voz se eleva con pasión mientras describe a su comunidad: “Exportamos panela, exportamos carne, producimos carne para todo el país. Tenemos un ecosistema hermoso, vivimos aquí y vivimos muy bien”.

La violencia de las protestas recientes ha dejado cicatrices profundas. La voz del padre Broncano tiembla al describir las secuelas: “Ahorita tenemos varios hermanos golpeados, tenemos un compañero (Mesías) en la lucha que está totalmente desfigurado. Dispararon directamente al cuerpo, ni siquiera al cielo, sino al cuerpo de las personas.” Sus gafas se empañan ligeramente mientras lucha por contener las lágrimas.

Los medios han guardado silencio sobre el tema, dice. A pesar de ese silencio, y de la violencia física y las amenazas, su fe permanece intacta. “Dios es nuestro padre y nos ama a todos, pero nos dio la posibilidad de decidir, nos dio la posibilidad de la libertad y en este caso la libertad de ayudarnos a nosotros mismos, de proteger lo que Dios nos ha dado.” Mira hacia su jardín, un pequeño paraíso de resistencia. “Lamentablemente, la imagen del padre se oscureció en algunas personas que cedieron”.

El padre Broncano vuelve su atención a su jardín, tocando con delicadeza un pétalo de flor. El gesto revela tanto la ternura de un sacerdote como la determinación de un luchador de resistencia. Su estrecha amistad con Carvajal Silva ha fortalecido la determinación de la comunidad. Juntos, se mantienen como pilares del movimiento: Carvajal Silva liderando las protestas, mientras el padre Broncano ofrece guía espiritual y un apoyo inquebrantable a quienes están en la primera línea. Su sotana no le impide estar codo a codo con su pueblo durante las manifestaciones, mostrando que su compromiso va mucho más allá de las oraciones y los sermones. Su presencia en Las Pampas sirve como un poderoso recordatorio de que la lucha por la justicia requiere no solo coraje en las calles, sino también el cultivo de la esperanza y el espíritu comunitario —como ese jardín que cuida con tanto esmero.

El viernes trae el mercado semanal en Las Pampas, un recordatorio vibrante de lo que está en juego. La plaza del pueblo rebosa de vida: mesas cargadas con zanahorias, tomates, papas, plátanos y bayas de toda variedad recién cosechadas. La abundancia de su tierra intacta se muestra con orgullo. Aquí, Carvajal Silva adopta el rol de un líder apasionado que ha unido a su comunidad en la resistencia. Colocando un pequeño altavoz y micrófono en medio del bullicio del mercado, atrae a una multitud. Los agricultores detienen sus ventas, reuniéndose con carteles hechos a mano que declaran su oposición a la mina. Su presencia electriza la plaza, su voz se eleva por encima del murmullo del mercado.

“No podemos rendirnos en estos momentos, tenemos que mantenernos firmes, compañeros, defendiendo [lo que tenemos], hemos trabajado duro y no vamos a permitir que nos quiten nuestro sustento”.

La multitud crece, su atención fija en este hombre delgado, de cabello negro, con un micrófono. “Hemos derramado lágrimas, hemos derramado sangre y no podemos permitir que esto continúe con impunidad”, continúa Carvajal Silva, su voz aumentando con emoción. “Vamos a continuar. Con su apoyo, voy a continuar. Solo, no podré hacer nada. Ustedes son mi fuerza, ustedes que han estado detrás, apoyando esta lucha que hemos estado llevando todo este tiempo”.

La respuesta es inmediata: vítores y gritos estallan de las familias reunidas. Canciones de resistencia y revolución se elevan en español, haciendo eco en las paredes de la iglesia donde esa cruz iluminada se mantiene como centinela. Debajo de la cruz, un mural cuenta la historia de esta gente en verso: una oración contra la minería que temen destruiría este lugar sagrado. A medida que las canciones se desvanecen en el aire de la montaña, la escena captura la esencia de Las Pampas. Estos no son los “manifestantes violentos” que afirman el gobierno y la industria, sino agricultores, familias y trabajadores unidos en la defensa de su agua, su tierra y un modo de vida tan profundamente arraigado como los mismos Andes.

La lucha aquí no es solo sobre la tierra y los recursos – es sobre la identidad misma, con a menudo profundas implicaciones legales. La negativa del gobierno a reconocer a Las Pampas y Palo Quemado como comunidades Indígenas convenientemente les permite evitar el requisito constitucional de consulta Indígena sobre proyectos mineros. Sin embargo, la vicepresidenta de CONAIE (Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador), Zenaida Yasacama, visitó a Carvajal Silva mientras Ricochet estaba allí para expresar solidaridad, afirmando lo que la comunidad ha sabido por mucho tiempo: su identidad Indígena es legítima, a pesar de los intentos del Estado de borrarla mediante tácticas coloniales de asimilación. CONAIE es la organización Indígena más grande y poderosa de Ecuador, uniendo a 14 nacionalidades Indígenas en sus luchas por los derechos territoriales, la justicia ambiental y la autodeterminación Indígena desde 1986.

Yasacama enfatiza que la violencia ejemplifica el intento sistemático del Estado de negar la identidad y los derechos Indígenas. “El gobierno se niega a reconocer a estas comunidades como Indígenas precisamente para evitar los requisitos adecuados de consulta”, explica. “Pero nos solidarizamos con Las Pampas y Palo Quemado: su identidad Indígena es legítima; su resistencia es justa”.

La negación del gobierno de su estatus indígena no es un accidente — es un movimiento calculado para evadir los procesos de consulta más rigurosos requeridos para los territorios Indígenas.

“Gente de afuera ha venido y ha dicho: ustedes son mestizos”, explica Carvajal Silva, rastreando el borrado sistemático de la identidad Indígena.

“Pero nosotros hemos regresado a examinar nuestras raíces”, con el respaldo total de CONAIE, dice.

“Todos nuestros antepasados bajaron de la sierra ecuatoriana — de Píllaro, de Tungurahua, de Cotopaxi. La mayoría de nosotros tenemos apellidos kichwas: Calos, Totas, Chucines, Chachas. No podemos cambiar la historia. Tenemos que entenderla y poder decir cuáles son realmente nuestras raíces”, afirma Carvajal Silva.

Hablando con Ricochet en la ciudad central de Puyo, Ecuador, días después, Yasacama está sentada en el balcón de un hotel local, rodeada por plantas esmeralda que pueblan el jardín del patio.

“Estos son los métodos que usan para destruir nuestras montañas desde dentro. Cada explosión, cada túnel que perforan, amenaza nuestra agua, nuestra paz, nuestra forma de vida misma”, dice.

La lluvia tamborilea con fuerza sobre el techo de lata mientras su voz se eleva por encima del aguacero. Como la primera vicepresidenta mujer de CONAIE, vestida con su blusa y falda tradicionales azules kichwas, quiere hablar directamente al gobierno canadiense y a las compañías mineras sobre la violencia desatada contra los Pueblos Indígenas y campesinos en Las Pampas que se oponen a la mina de Atico.

“Hoy alzamos la voz para que el mundo nos escuche. Vivimos en la tierra, estamos en la lucha, estamos sembrando diariamente en nuestro territorio”, declara, con su largo cabello negro recogido, su pequeña figura inclinada hacia adelante. “Escuche, Gobierno de Canadá, señor Primer Ministro de Canadá, le pedimos amablemente que respete los derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas aquí; si quieren ayudar, no destruyan nuestros territorios”.

La lluvia se intensifica mientras ella describe el terror que las operaciones mineras han traído a sus comunidades: “No podemos vivir en guerra; no podemos vivir con este miedo. Nuestros niños están asustados todos los días, cuando oyen el helicóptero, cuando los camiones pasan todos los días. No vivíamos así antes, pero hoy sí. ¿Hasta cuándo continuará este pisoteo de los derechos de los pueblos Indígenas? ¿Dónde está el derecho de los niños, dónde está el derecho de todos los Pueblos Indígenas a vivir en paz?”

Mirando hacia el exuberante jardín más allá del balcón, hace un llamado a la acción inmediata: “No vivimos en paz, por eso hoy queremos que ustedes [Canadá] retiren inmediatamente a estas empresas mineras que están en la provincia de Cotopaxi, Las Pampas y otros territorios aquí en Ecuador que están siendo amenazados”.

La injusticia de la criminalización pesa en sus palabras: “Estamos pasando por mucho, estamos siendo judicializados, sin tener ninguna culpa, solo por defender nuestros territorios. Señor Primer Ministro de Canadá, esta es la realidad de lo que nos está pasando”.

Mientras tanto, Carvajal Silva está esperando saber cuándo será llevado a juicio para enfrentar cargos penales por su oposición a la mina.

El estudiante de derecho de la Universidad de Virginia, Jacson Khandelwal, es parte de un equipo de abogados voluntarios que ayuda a defender a Carvajal Silva y otros.

“Lo que le está pasando a Juan es un caso clásico de uso como arma de las leyes contra el terrorismo y el crimen organizado contra defensores ambientales”, dice. “La empresa fue a la Fiscalía — que es un fiscal del gobierno — y afirmó que Juan los estaba intimidando, que estaba cometiendo actos de terrorismo, que todo esto era parte de un esquema de crimen organizado. Cualquier fiscal razonable vería que Juan no es un terrorista, pero la Fiscalía decidió tomar el caso de todos modos”.

La táctica es común, continúa.

“Esto pasa en todo el mundo con defensores de derechos humanos y de tierras durante tiempos de conflicto. El gobierno tiene estas leyes que están destinadas a atacar a narcos y carteles. En cambio, tienes empresas que van a la Fiscalía diciendo: ‘Oh, pero este defensor de la tierra también está cometiendo estos crímenes’”.

La frustración de Khandelwal es palpable. “Eso es lo que hace que este proceso penal contra Juan parezca tan corrupto. Claramente no es un terrorista. Claramente no está involucrado con los narcos. Claramente no forma parte de ningún crimen organizado. Es parte de un movimiento social”.

“El problema”, continúa, “es que el gobierno está del lado de la empresa y su denuncia, a pesar de todas las pruebas que muestran que Juan no es un terrorista ni un criminal organizado. Realmente expone las fallas del sistema de justicia penal de Ecuador — el hecho de que estas leyes pueden ser usadas contra personas inocentes que en realidad están haciendo un buen trabajo”.

Khandelwal enfatiza su punto final: “Estas leyes sobre terrorismo y crimen organizado e intimidación no están destinadas a personas como Juan. Están siendo utilizadas como armas contra él por hacer trabajo de defensa ambiental y de derechos humanos. Las 12 investigaciones en su contra no son solo casos — son un intento sistemático de silenciar la defensa ambiental mediante intimidación legal”.

"Lo único que tenemos seguro en la vida es la muerte"

Sin embargo, el mensaje de Carvajal Silva a las empresas mineras extranjeras, particularmente Atico, es claro: “Ustedes vienen de un país extranjero a invadir nuestras tierras, a intimidarnos, y nos acusan, cuando los verdaderos terroristas son ustedes — los que quieren destruir nuestra tierra. Están cegados por el poder económico y no miran atrás para ver que dentro de estos territorios hay seres humanos que luchan por sobrevivir, por poner comida en la boca de nuestros hijos, nuestras familias”.

El Frente Nacional Antiminero de Ecuador y CONAIE han anunciado planes para una resistencia sostenida, incluyendo un campamento en Quito. Pero por ahora, la gente de Las Pampas y Palo Quemado permanece en un limbo incómodo — su victoria legal contra el Decreto 754 socavada por su aplicación continua, su resistencia pacífica enfrentada con represión militarizada, su identidad indígena negada para facilitar la extracción.

Carvajal Silva encuentra fuerza en su fe y en la unidad de su comunidad. “Todo queda en manos de Dios”, dice. “Si yo me rindo, ellos se rinden. No puedo rendirme, no debo. Tengo que mantenerme fuerte para poder apoyar a mi pueblo con el espíritu de seguir luchando”.

Habla de la muerte con la aceptación tranquila de alguien que la ha enfrentado muchas veces. “Nuestro mejor aliado, y lo único que tenemos seguro en la vida, es la muerte. Por lo tanto, no debemos tenerle miedo. Es bueno morir haciendo algo por tu pueblo, algo que quede como referencia para otros. Yo lo haría. Es lo mejor que sale de una persona que lucha con el corazón, sin la meta de quizás ganar un salario o alcanzar un puesto político”.

A medida que cae la noche sobre Las Pampas, surge la esperanza más profunda de Carvajal Silva: “La belleza sería terminar esta lucha y vivir la vida con mi pueblo en esta hermosa tierra que tenemos. Queremos que nuestras futuras generaciones vivan en paz, no que continúen como están hoy”.

Hasta entonces, él está listo para defenderlo todo — los ríos con los que creció, los árboles que crecieron junto a él y el modo de vida que sostiene a su comunidad, tal como ha sostenido a generaciones antes.

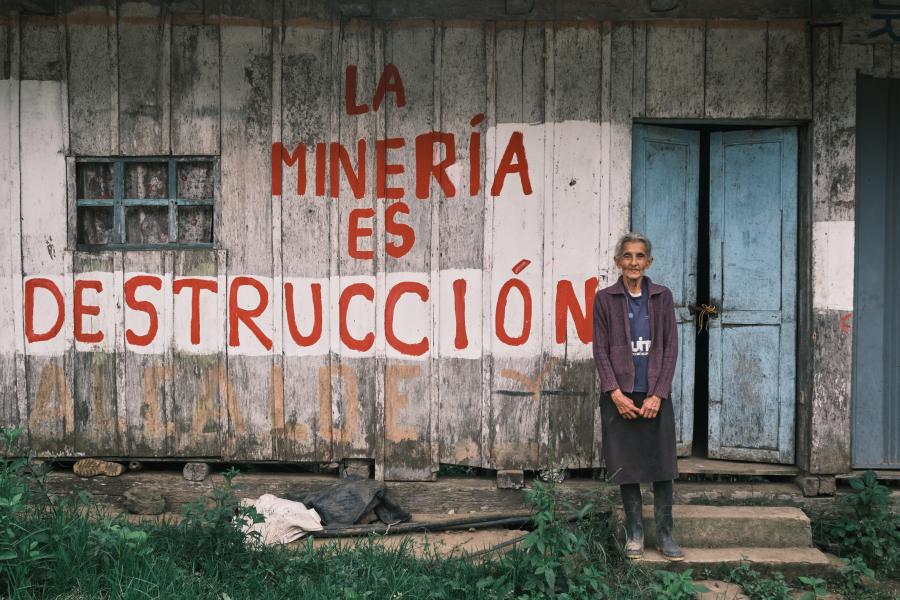

El paisaje fuera de Las Pampas. Foto por Ian Willms

En diciembre de 2024, la periodista Indígena Brandi Morin y el fotoperiodista Ian Willms viajaron a Ecuador en vísperas de un nuevo tratado de libre comercio con Canadá para informar sobre el conflicto entre el pueblo Shuar y una empresa minera canadiense.

Lee la primera, segunda y tercera parte de esta serie.