By Bryan Bixcul (Maya-Tz’utujil), SIRGE Coalition Global Coordinator

The United Arab Emirates Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP) is a three-year process established by Parties at COP28 to facilitate discussions on pathways for achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement in a manner that is inclusive and leaves no one behind. It was created in response to widespread recognition that climate transitions can generate social, economic, environmental, and labour impacts, particularly for workers, communities, and Indigenous Peoples, and that just transition efforts must address these dimensions as countries shift away from fossil fuels.

While the JTWP does not prescribe how countries must implement their transition strategies, it aims to deepen understanding of the social, economic, environmental, and labour dimensions of climate transitions and to highlight approaches that can support both sustainable development and poverty eradication. Through dialogues and related work, the programme encourages Parties to consider issues such as decent work, labour rights, social protection, gender equality and meaningful and effective social dialogue. It also recognizes the importance of broad engagement, including the participation of Indigenous Peoples, workers, local communities, youth, and other groups most affected by the transition.

For the last two years, governments gathered to negotiate the “outcomes” of the Just Transition Work Programme - the political agreement that captures what countries agree on for that year. These outcomes are adopted as a formal decision under the Paris Agreement and reflect the key messages, priorities, and areas of focus that emerged from its work. They are not legally binding, but they matter: they shape how governments frame just transition policies, signal political direction, and influence future negotiations.

For Indigenous Peoples, engaging and securing strong rights-affirming outcomes in the JTWP is essential to ensure that their collective rights are recognized as core elements of just transition pathways. Without explicit rights-based framing, countries may design transition strategies that reproduce the same extractive, exclusionary practices that have historically harmed Indigenous Peoples. This makes it important to examine the substance of the decision, its advances, its gaps, and the unfinished business that will shape the next phase of the Just Transition Work Programme.

No Agreement on Phasing Out Fossil Fuels—Again!

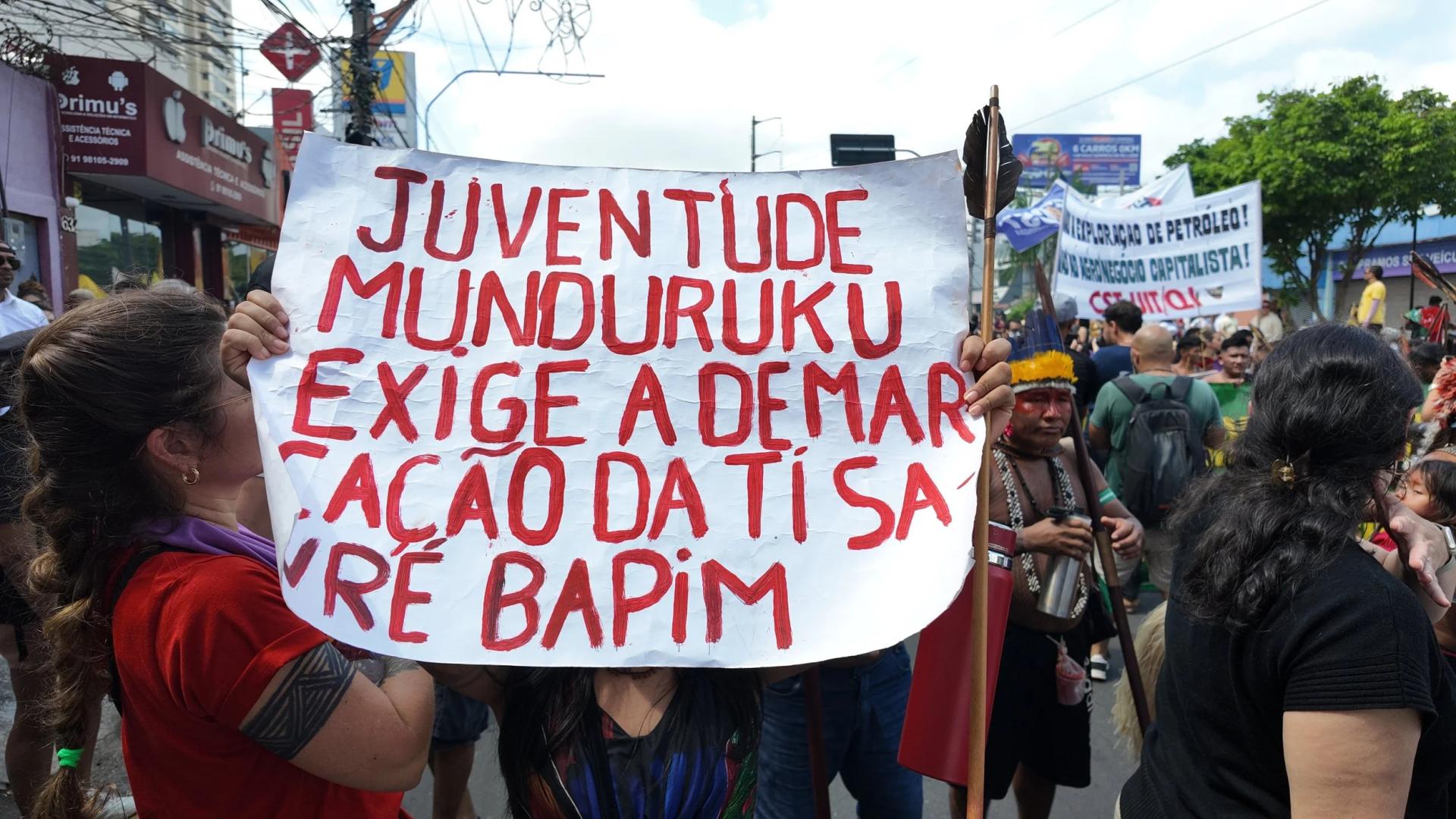

One of the clearest signals emerging from this year’s negotiations is what is missing from the final outcome: there is still no agreement on phasing out fossil fuels. The language on fossil fuels that many countries championed was ultimately dropped, despite being one of the most critical foundations for any credible just transition. Without a commitment to rapidly phase out fossil fuels, the Just Transition Work Programme risks becoming disconnected from the structural economic shifts that science demands and that justice requires. For Indigenous Peoples, who are disproportionately impacted by fossil fuel extraction, this omission is especially alarming. A just transition cannot exist without confronting the root causes of the climate crisis, and this year’s outcome once again reflects the political resistance that continues to block collective progress.

Beyond the JTWP, the question of phasing out fossil fuels surfaced repeatedly across other negotiation streams, including the cover decision, the Brazilian Presidency’s Mutirão draft, and in mitigation negotiations, but the resistance from a handful of powerful fossil-fuel-exporting countries was overwhelming. Even in the negotiation streams where fossil fuel commitments are more appropriately addressed, Parties were unable to reach agreement, and any explicit references to fossil fuel phase-out or phase-down were ultimately removed from the final texts. The political resistance was so strong that no part of the COP30 decisions managed to retain any language that would signal a collective move away from fossil fuels.

Outside the formal negotiations, Brazil attempted to build political momentum through a voluntary “roadmap” for transitioning away from fossil fuels, but this initiative also failed to gain sufficient support and was never released. In reaction to the disappointing negotiations, a group of 24 countries -led by Colombia- stepped forward to sign the Belem Declaration during COP30. The pact commits signatories to cooperate in developing a roadmap towards fossil fuel phase-out, grounded in the best available science, and aligning with the 1.5 °C limit. Countries including Colombia, the Netherlands, Mexico, and Costa Rica signed on, and Colombia and the Netherlands announced they will co-host an International Conference in April 2026 in Santa Marta focused on the transition away from fossil fuels. Although this declaration does not carry the legal weight of a formal UNFCCC decision, it signals emerging political momentum and provides an alternative track of ambition as the UNFCCC has fallen short.

Removal of References to the Risks of Transition Minerals Extraction

The negotiations also revealed deep political tensions around the role of transition or “critical” minerals in the energy transition. Early references to the social and environmental risks of the extraction of minerals deemed critical for the transition appeared in the informal note prepared by the UNFCCC secretariat following the four JTWP dialogues and contact group negotiations in Belem. Those informal summaries reflected the actual content of the dialogues and negotiations, where numerous Parties, Indigenous Peoples, and stakeholders emphasized the need to address the environmental and human rights risks associated with the expansion of mining for lithium, copper, nickel, cobalt and other minerals in the text. Yet none of this language survived once the formal negotiated text emerged. In the transition from the secretariat’s informal note to the Parties’ negotiated text, every reference to “critical” minerals, mining, or related environmental and social risks were deleted.

This removal did not happen by accident. As we tracked throughout the negotiations, a handful of countries pushed back aggressively against any mention of critical minerals, arguing that it was outside the mandate of the JTWP to address supply chains, extraction impacts, or the governance of transition minerals. They also argued that such references would infringe on countries' right to development. Their opposition succeeded, and the final decision contains no acknowledgment of the environmental, social and human rights risks associated with the expansion of mining for transition minerals, despite this being one of the most pressing justice issues in the shift to renewable energy technologies.

This removal stands in sharp contrast to the real-world experiences shared during the JTWP dialogues, especially the one celebrated in Ethiopia where a small delegation of Indigenous Peoples engaged in dialogue with Parties to share about the environmental and human rights impacts associated with mining for transition minerals. For Indigenous Peoples, who face both ongoing fossil fuel extraction and a new wave of mineral extraction for the energy transition, the removal of this language represents a major gap in the COP30 outcome and underscores how politically sensitive the issue has become.

The Most Significant Wins for Indigenous Peoples in the JTWP

Despite major challenges in the negotiations, COP30 delivered some important advances for Indigenous Peoples rights, particularly through the JTWP in paragraph 12(i) and paragraph 18, which now function together as the strongest rights-based language ever adopted under the Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP), and some of the clearest affirmations of Indigenous Peoples’ rights in any UNFCCC decision to date.

As stated in paragraph 12(i) of the COP30 decision under the JTWP:

“The importance of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and of obtaining their free, prior and informed consent in accordance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the importance of ensuring that all just transition pathways respect and promote the internationally recognized collective and individual rights of Indigenous Peoples, including the rights to self-determination, and acknowledge the rights and protections for Indigenous Peoples in voluntary isolation and initial contact, in accordance with relevant international human rights instruments and principles; ”.

This paragraph is consequential because it establishes, for the first time in the JTWP, a rights-based baseline that applies to every sector and every just transition pathway that governments pursue in the name of climate action. By explicitly affirming Self-determination, Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), paragraph 12(i) elevates Indigenous Peoples’ rights from the sidelines to core guiding principles that all just transition actions must respect and promote. This is also the first time a COP decision explicitly references Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation and Initial Contact (PIACI), marking an unprecedented recognition of their rights and the specific protections they require within the climate regime.

Even though the JTWP is not legally binding, this language carries significant political and normative weight: it shapes how governments interpret their responsibilities under the Paris Agreement, influences national legislation and climate planning, and sets expectations for governments, development banks, investors, and private companies involved in energy, minerals extraction, land-use change, infrastructure projects, carbon market projects, large-scale biofuel plantations, hydrogen hubs, industrial corridors linked to energy infrastructure, etc. Because countries will increasingly justify these activities as necessary for their decarbonization pathways or for meeting Paris Agreement goals, Indigenous Peoples can reasonably interpret these actions as falling under the umbrella of the Just Transition Work Programme.

Paragraph 12(i) therefore creates a normative international standard that Indigenous Peoples can use in several ways. 12(i) can be cited when requesting that governments and companies respect Self-determination, obtain FPIC, protect PIACI, or prevent rights violations in transition-related activities. They can reference it in national consultations, environmental impact assessments, court cases, administrative complaints, and complaints to UN human rights bodies, arguing that States committed to ensuring all transition pathways respect internationally recognized Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

Paragraph 12(i) can also be used to pressure multilateral development banks and private investors whose financing decisions are increasingly expected to align with UNFCCC outcomes and robust human rights due diligence. In this sense, paragraph 12(i) becomes a powerful accountability tool.

Importantly, Paragraph 13 of the decision also explicitly invites Parties and non-Party stakeholders to consider the key messages in paragraph 12 when designing, implementing, and supporting just transition pathways. This means that governments, financial institutions, and companies are directly encouraged to use paragraph 12(i) as a reference point in their climate policies and investments, reinforcing its relevance beyond the UNFCCC negotiations.

Although paragraph 12(i) affirms that all just transition pathways must respect Indigenous Peoples’ collective and individual rights, it does so at the level of principle rather than implementation. It does not specify how these rights should be applied in the mining sector, what safeguards are needed, how due diligence ought to be conducted, how States should oversee transition-mineral supply chains, or what forms of accountability are expected when rights are violated. This is why explicit language on the risks of mining was essential: it would have helped operationalize paragraph 12(i) by translating its broad normative expectation into clearer guidance, stronger safeguards, monitoring provisions, and practical accountability measures for one of the sectors that is already driving major Indigenous Peoples’ rights violations under the banner of climate action.

Paragraph 18 further strengthens this rights-based foundation by explicitly referencing both the UNDRIP and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). This combination is rare in UNFCCC decisions and highly consequential: it links the just transition not only to States’ human rights commitments, but also to the responsibilities of companies, investors, and financial institutions. It creates a clear normative and interpretive obligation that transition-related activities must be consistent with Indigenous Peoples’ rights and with international standards for human rights due diligence.

It is also important to acknowledge the countries that stood with Indigenous Peoples throughout these negotiations. Panama, in particular, consistently championed the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples’ rights and delivered powerful statements in support of Indigenous Peoples’ Self-determination, FPIC, protections for PIACI, and safeguards to address the impacts of transition minerals extraction. Their leadership helped maintain the integrity of paragraph 12(i) in the final decision.

A New Opportunity: The Just Transition Mechanism Must Center Indigenous Peoples Rights and Address the Extraction of Transition Minerals

Paragraph 25 opens a new chapter by developing a Just Transition mechanism, what many including Indigenous Peoples think of as a long-term institutional space that will shape how countries cooperate, set priorities, and design transition pathways beyond the current Work Programme. The decision calls for a mechanism that will “enhance international cooperation, technical assistance, capacity-building and knowledge-sharing, and enable equitable, inclusive just transitions,” with a draft decision on its operationalization to be prepared by the subsidiary bodies in June 2026 and adopted at COP31 later that year. This timeline creates an immediate political opportunity. Parties and non-Party stakeholders, including Indigenous Peoples, have been invited to submit views on this process by 15 March 2026.

For Indigenous Peoples, this mechanism must become a space where full and effective participation in decision-making is guaranteed, not merely consultation. It must embed Indigenous leadership in both the design and the oversight of just transition policies. Importantly, this can also become the institutional home for addressing issues not currently addressed by the JTWP: i.e., the impacts of transition or “critical” minerals extraction. It can advance the development of clear standards, safeguards, and expectations for protecting Indigenous territories, including discussions on exclusion or no-go zones for extractive activities, particularly in PIACI territories. The removal of explicit mining language from the COP30 decision makes this even more urgent.

The new mechanism offers a chance to correct this course. It can operationalize the rights affirmed in paragraph 12(i), translate the standards referenced in paragraph 18 into concrete safeguards, and create monitoring and accountability tools that apply directly to mineral supply chains, infrastructure corridors, and renewable energy expansion. But this will only happen if Indigenous Peoples are meaningfully involved in designing the mechanism from the outset, shaping its mandate, governance, functions, and safeguards. Paragraph 25 is therefore a call to ensure that the next phase of global just transition governance confronts the realities of issues like mining and places Indigenous Peoples’ rights at the center of the just transition.